OPEC is suffering because it miscalculated–but so has everyone else

The world isn’t going quite the way Saudi Arabia expected when it led OPEC to declare a pricing war against US shale drillers last year by flooding the market with crude oil. Far from being a quick kill, shale drillers have stubbornly held on, and OPEC has suffered along with them.

The world isn’t going quite the way Saudi Arabia expected when it led OPEC to declare a pricing war against US shale drillers last year by flooding the market with crude oil. Far from being a quick kill, shale drillers have stubbornly held on, and OPEC has suffered along with them.

But, as its members return home today after their latest biannual meeting in Vienna, OPEC’s problem isn’t only that it was wrong-footed by oil prices, historically the most potent tool for punishing and pushing out unwanted competitors. It’s that seemingly all the traditional tools for determining strategy have failed this time.

And not only for OPEC—the usual divining rods have suddenly gone faulty for the entire energy industry, along with governments, analysts, scholars, and journalists. All wrongly anticipated how low prices would drop and for how long, along with the degree to which oil companies and petro-states would keep drilling despite it all.

“We’re not good at predicting prices and not good at predicting costs, and all this has geopolitical implications,” Jeff Colgan, a professor at Brown University, told Quartz.

In Vienna today, OPEC rejected proposals by Venezuela and other members to cut production and possibly force prices back up. Instead, the cartel raised its production target to what members actually produce—31.5 million barrels a day—in a decision to grimly to stay the course and keep trying to sweat shale drillers out of business and push down US oil production. That sent oil prices sharply down, with the US benchmark falling again below $40 a barrel. But soon enough, the cartel believes, prices will rise sharply, and OPEC will be back in the catbird seat. Russia, too, the largest non-OPEC producer, is producing at a breakneck pace.

In so deciding, the drillers have accepted the lead of Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi (pictured right). But the most hopeful estimate—if you happen to be OPEC or Russia—is that, if things actually break their way, it will take until the second half of next year for prices to begin rising. More likely, according to many analysts, is another year of prices more or less in the current band. And after that, says the International Energy Agency, prices will go back to just $80 a barrel, and there only in 2020. That’s almost double today’s price, but about 20% lower than the $100 a barrel to which OPEC had become accustomed in recent years.

Everyone thought this time would be like always

When it launched the strategy last year–an effort to hold onto its market dominance against a sudden, 4.5-million-barrel-a-day torrent of US shale oil—Saudi Arabia thought the battle would go relatively quickly. It persuaded its fellow cartel members to go along.

But OPEC’s miscalculation isn’t entirely its own fault. Instead, the culprit is that the tools that worked for so long—some, such as flooding the market to sweat out rivals, have been around since industry pioneer John D. Rockefeller 150 years ago—seem never to have faced such a test as now.

The special challenges of the current era include the fact that there are more oil producers than ever, and that a new player—shale oil—isn’t subject to the usual rules of oilfield economics. That is, shale can be developed much faster than a conventional field, and be maintained for less investment.

Among metrics that have been upended by the new age are fundamental yardsticks such as supply, demand (paywall), oil prices, and the cost to drill.

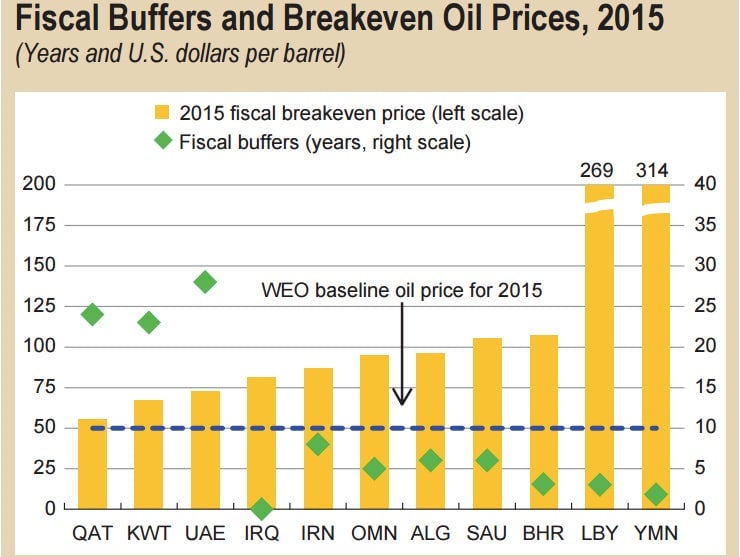

In one specific example, in a paper published in November by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Blake Clayton and Michael Levi critiqued a widely used gauge of the geopolitics of energy—an oil-producing country’s “fiscal break-even point.” This tool (see the IMF’s version, right) simply divides a petro-state’s daily oil production by its national budget, and arrives at the oil price required to be in fiscal balance.

The presumption underlying the tool is that, if a nation such as Russia or Saudi Arabia receives less than the break-even price for a sustained period, it will be in trouble, since such states are believed to rely on generous social spending to mollify opponents. But Clayton and Levi point out that neither Russia nor Saudi Arabia have budged despite receiving oil prices far below their respective fiscal break-evens for more than a year; on the contrary, both have wrong-footed geopolitics thinkers by doubling down on policies that can only make fiscal matters worse.

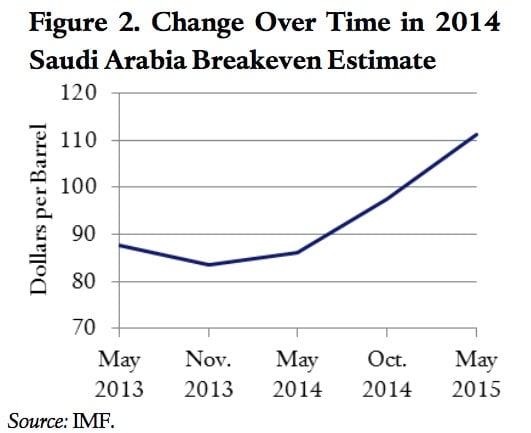

It also bothers the two writers that break-even estimates are erratic, often for unexplained reasons (see chart, left). Levi notes additionally that the tool fails to take into account numerous options available to a country to adjust. In Russia’s case, president Vladimir Putin allowed the value of the ruble to drop by about 50%—Russia is paid in dollars but spends rubles locally—which almost entirely compensated for the price drop. And both Russia and Saudi Arabia have large cash reserves that they have been willing to spend down.

The CFR analysis is solid as far as it goes. But while Russia and many of the OPEC nations have held on fine, some are hurting, and the battle isn’t over—it’s comparatively easy to maintain a brave face while privately hoping that prices go up; faces could change if prices stay more or less where they are for a much longer period.

Countries that are under particular stress include Algeria, Iraq, Nigeria, and Venezuela, Medley Advisers’ Yasser Elguindi told The Fuse. “These are all countries that I think will be challenged in the coming years if they don’t begin to adjust spending and look for new sources of income,” Elguindi said.

It’s true that analysts need to up their game on all the models: We need to know Putin’s true pain threshold. Likewise, toolmakers can be smarter judging the role of supply and demand in how much drillers charge for creating an oil well. But the rationale behind the tools is solid, and the tools are necessary. They just need to be better.