The rise of France’s far-right from the 1980s to today, charted

“We are without question the first party of France.” That was the verdict of Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front (pictured above), after her party won the largest share of votes in the first round of regional elections yesterday (Dec. 6).

“We are without question the first party of France.” That was the verdict of Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front (pictured above), after her party won the largest share of votes in the first round of regional elections yesterday (Dec. 6).

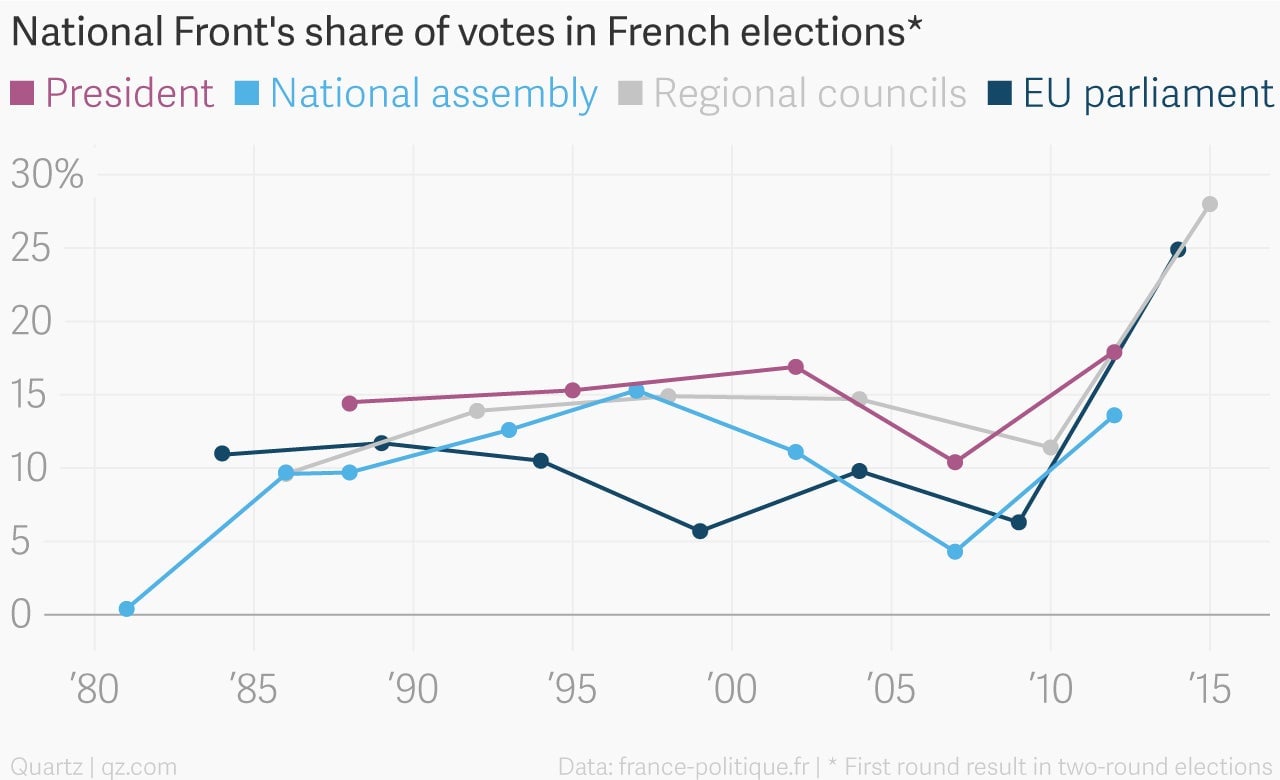

The anti-immigration party, which saw a surge in the polls after the deadly terror attacks in Paris last month, received 28% of the vote across the country, leading in six of the country’s 13 regional councils.

The second round of run-off voting this Sunday (Dec. 13) may put a dent in that support, if other parties unite behind a single candidate to prevent the National Front from taking control. This, somewhat perversely, could strengthen the far-right party ahead of the coveted presidential election in 2017. “The French people are sick and tired of that old political world,” National Front leader Marine Le Pen said of the mainstream center-left and center-right parties.

The trend is clear: the far-right is steadily gaining support in France, moving ever closer to the real levers of power after decades on the fringes.

Regional councils don’t have a huge amount of power but they do have oversight over local transport and some aspects of the school system. They also manage budgets for economic development and cultural programs. National Front candidates for regional council presidents, including Marine Le Pen and her 25-year-old niece Marion Marechal-Le Pen, have pledged to put their party’s policies into action by doing things like cutting funding for family-planning centers and the arts. This executive experience could bolster the party’s bona fides ahead of the presidential election.

Although the National Front also won a landslide victory in last year’s election for the European Parliament, those Brussels-based roles don’t carry the same profile or power as domestic political positions. In the 2012 elections, the far-right party gained only two of the national parliament’s 577 seats and Marine Le Pen came a distant third in the presidential race. The momentum that the party is now building seems destined to improve those results significantly—even before this weekend’s regional election victory, Marine Le Pen has consistently placed first or second place in the polls for France’s next president.