How journalists can handle America’s blatantly lying politicians

Politicians lie. To varying degrees, they always have. But it is starting to seem that that truism is more true than it has ever been.

Politicians lie. To varying degrees, they always have. But it is starting to seem that that truism is more true than it has ever been.

In 2012, American political commentator Charles P. Pierce claimed that the Republican Party was setting out in search of the “event horizon of utter bullshit” at its national convention that year. It wanted:

to see precisely how many lies, evasions, elisions, and undigestible chunks of utter gobbledegook the political media can swallow before it finally gags twice and falls over dead.

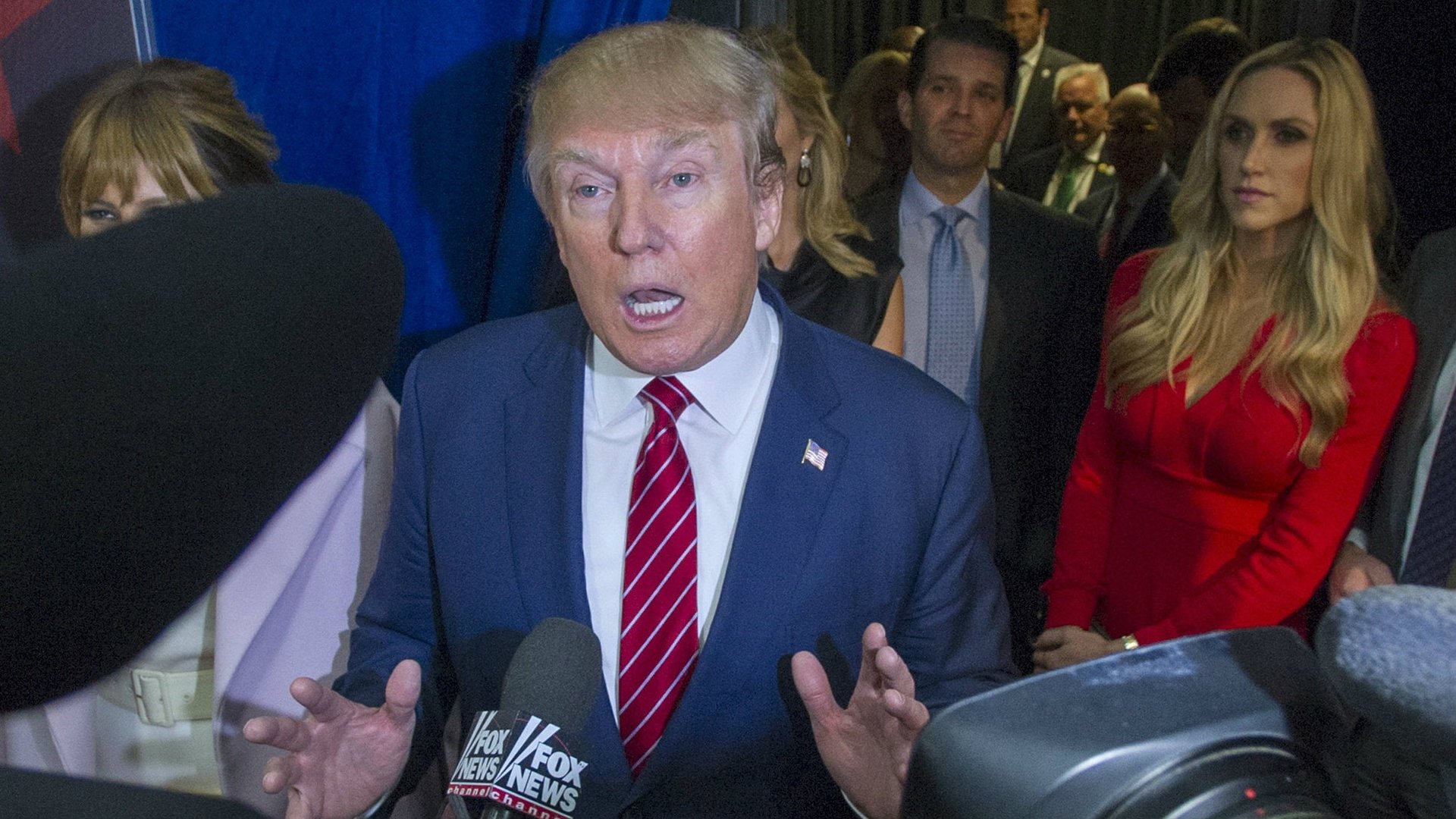

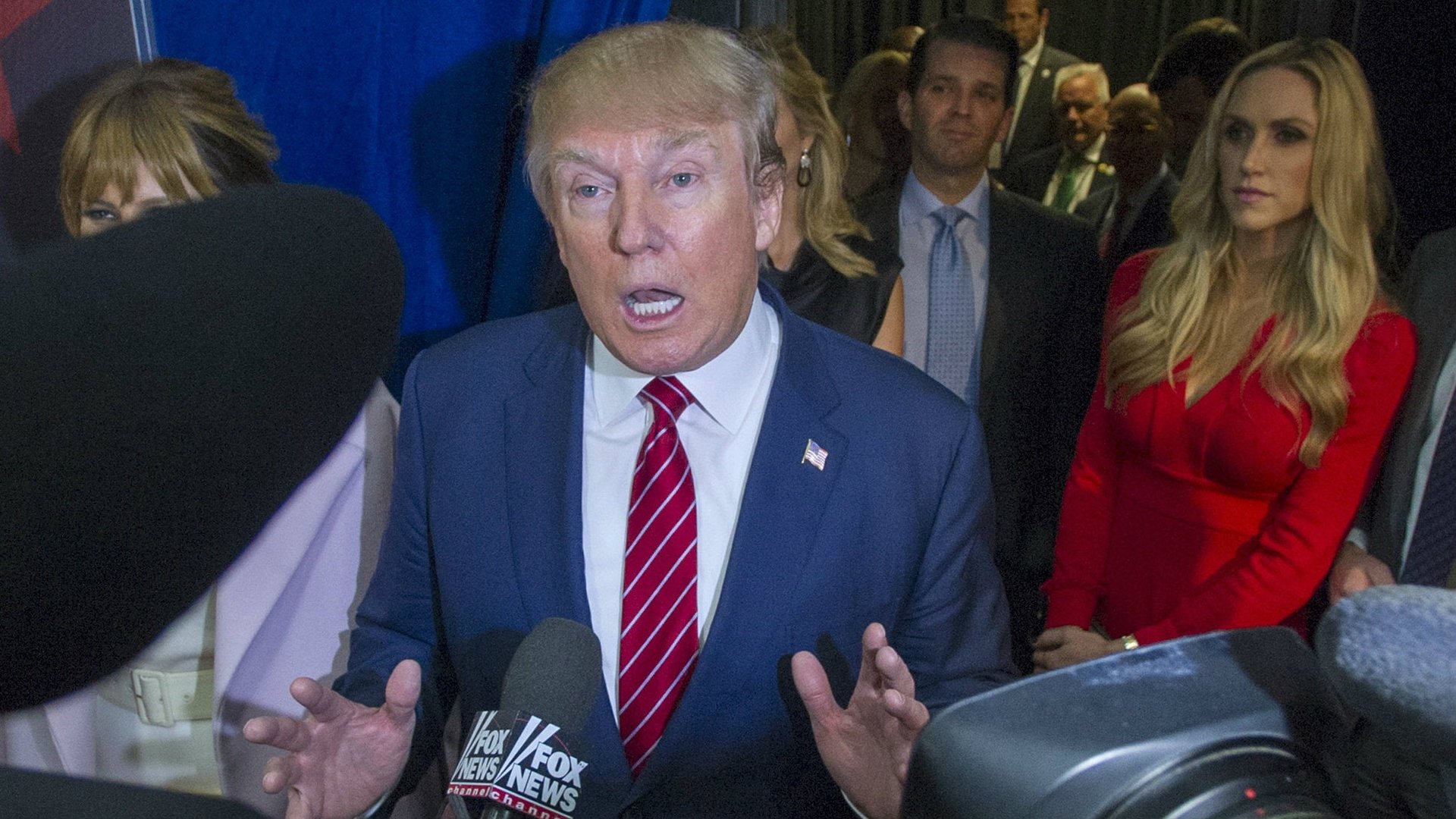

And then along came Donald Trump and Ben Carson, who proceeded to knock things up a notch or two. These two candidates for the Republican presidential nomination for 2016 have appeared to reach entirely new levels of political indifference to the truth.

Carson—who drew mockery for suggesting Egypt’s pyramids were built to store grain—has had several key anecdotes in his autobiography challenged. Meanwhile, fact-checking website Politifact has rated only one of his substantial claims during the campaign as “mostly true.” The rest were either “half true,” “mostly false,” “false,” or “pants on fire.”

Despite leading the race, Trump has made so many obviously or demonstrably false statements along the way that some experts have been forced to completely re-think long-held assumptions about:

the rules [of politics and elections] … and what the penalty would be for violating them.

In the past, a politician saying something factually inaccurate was cause for humiliation. Now there appears to be few consequences, if any. If journalism is supposed to be a force for truth, accountability, and enlightenment in the political process, then it appears to be failing on the biggest of stages.

Why?

Thoughtful analyses of this situation almost always point to one of two possible explanations: generally, that the media is “biased,” and/or that politics has become “dumbed down” for easier audience consumption—just like any other kind of entertainment.

Like many others, journalist Matt Taibbi blames journalism’s blunted edge on the commercial pressures in the newsroom:

We in the media have spent decades turning the news into a consumer business that’s basically indistinguishable from selling cheeseburgers or video games.

Though there is certainly some truth in that argument, it has a couple of major weaknesses.

One is that even if we do accept that there has been an increase in “soft” news, that doesn’t mean that the “hard” forms have gone away. Plenty of journalists are still out there asking the tough questions and undertaking comprehensive analysis.

Another is that the economic climate in the media means journalists need to keep justifying (or funding) their own salaries, and there is no better way of doing so than by “scooping” a rival, or taking down a big political name. Financial pressure often creates more journalistic adversarialism.

It would take a very cynical person to suggest that every working journalist today has sold their soul to corporate interests, or that there isn’t still a huge audience out there for investigative reporting, hard-hitting interviews, and the exposure of political malfeasance.

As proof of this, one only has to think about the extensive probing around the Whitehouse Institute scholarship awarded to Frances Abbott, or Sarah Ferguson’s post-2014 budget interview with Australia’s then-treasurer Joe Hockey.

So, while good journalism is still out there, there are few consequences for politicians who lie.

An alternative explanation

If we assume that journalists and politicians are co-dependent adversaries with competing interests (one side with political goals, the other dedicated to facts and truth), then there has been—as my colleague Brian McNair puts it—a “communicative arms race” going on between the two.

Right now, politicians tend to win the battles—not just because they have better resources (such as whole teams of media advisors), but because journalists (their enemy) operate in such predicable ways.

Journalism is an incredibly homogeneous activity. Around the globe, almost without exception, it looks the same, sounds the same, and follows same arbitrary rules. American media professor Jay Rosen uses the term “isomorphism” to describe this, and the consequence is that politicians have slowly worked out how to game their opponents.

For example, genre and production standards mean that if you repeat the same five-to-ten-second soundbite during an interview (no matter the question being asked), chances are that soundbite will survive the editing process and appear in the television news that evening.

Similarly, the limitations on space, time, and attention, coupled with an obsession with timeliness, mean it is quite easy for politicians to circumvent thorough journalistic analysis while still feigning transparency. This was evident when heavily “spun” pronouncements or weak policies were regularly released just before major newsroom deadlines.

Now, it is commonplace to bury bad news by releasing it late on the Friday before a long weekend—or, as in one famous example, waiting for a much bigger news story to come along.

Journalists are also heavily dependent on getting exclusives and “insider” information. Politicians can thus easily threaten to limit a less senior reporter’s access if their coverage ever becomes too critical.

All of this is made possible, ironically, by the objectivity on which journalists stake their reputations. Taibbi notes that when a lie gains attention, politicians can just:

Blame the backlash on media bias and walk away a hero.

Too often this objectivity means journalists will not call out or vigorously pursue a false statement for fear of being seen as biased, and instead rely on one of that person’s political opponents to do the job instead. This leads to “he said, she said” reportage that leaves ordinary citizens little the wiser.

I did an interview recently with a well-known Australian media producer who called this, appropriately, “balance disease.”

How to fix it

There are a number of things that may help journalists start winning the battle of truth.

First, and perhaps most importantly, we need to look very closely at the way we train future journalists, particularly in academic contexts. We need ensure that journalism programs are not a homogenizing force that leave graduates open for exploitation by clued-up politicians. We should encourage student experimentation, rule-breaking, and creativity, not deferential adherence to pre-defined operational standard.

Second—given the failure of “fact checking” as a practice to solve the issue of political lies, and the now widely shared assumption that politicians will lie regularly—journalists need to start paying less attention to “facts” and more attention to the internal logic of a politician’s own arguments.

Finally, journalists themselves need to regain some confidence. The co-dependence means that politicians need journalists just as much as journalists need access to politicians. If every journalist ended an interview the moment a politician clearly lied, or refused to answer a question, they would quickly realize just how much firepower they really have at their disposal.