Italy has way more problems ahead of it than its election results

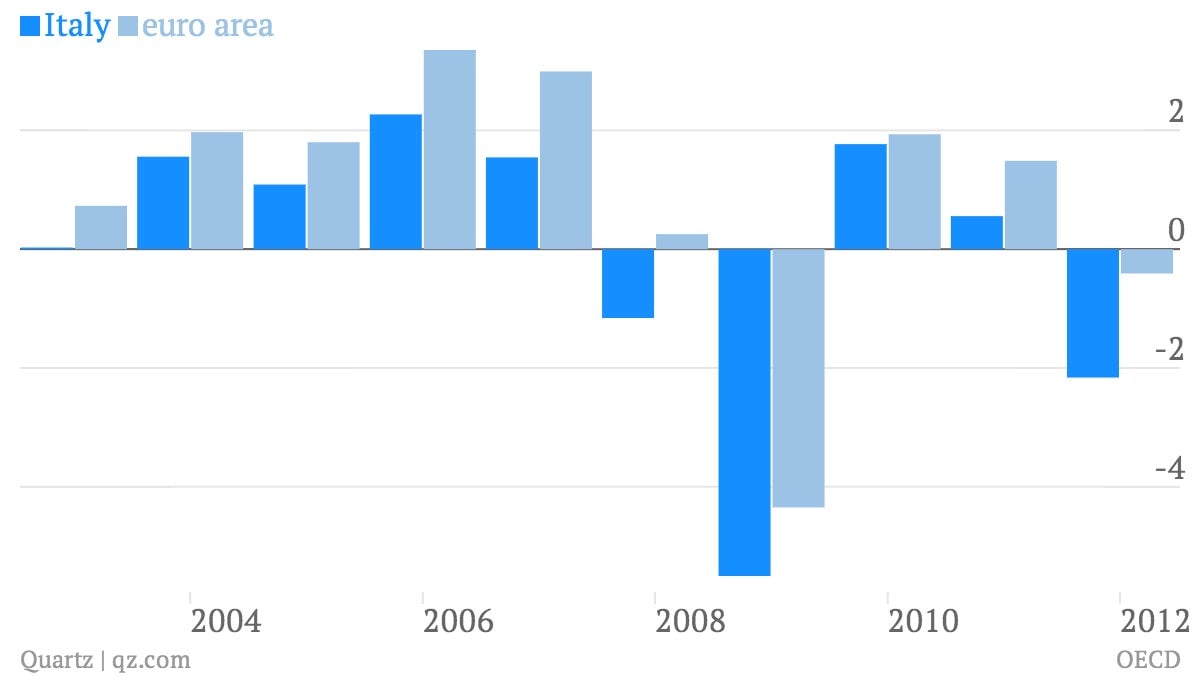

It’s no wonder Italians piled into the clown car. Their economy has been contracting for a year and a half, the longest recession in two decades. Sure, they don’t want to keep austerity in place. But a return to the Berlusconi years of 2001-06 and 2008-2011 isn’t that inviting either. The country has seen feeble growth in the last 10 years, compared with the euro area:

It’s no wonder Italians piled into the clown car. Their economy has been contracting for a year and a half, the longest recession in two decades. Sure, they don’t want to keep austerity in place. But a return to the Berlusconi years of 2001-06 and 2008-2011 isn’t that inviting either. The country has seen feeble growth in the last 10 years, compared with the euro area:

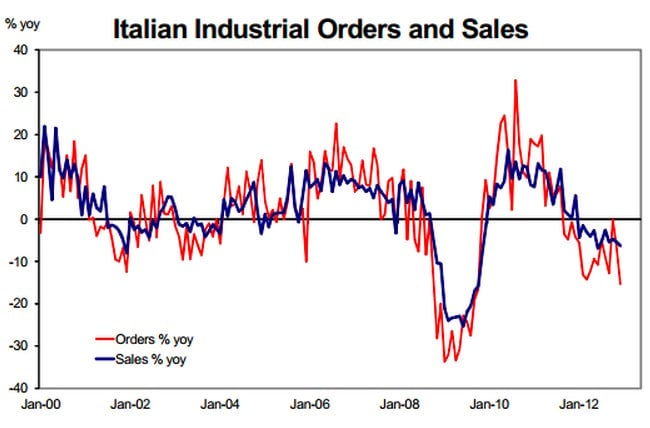

Italy has long been one of the sicker men of Europe. And the prognosis isn’t good. For instance, here’s a look at its industrial sector, returning to shrinkage after seeming to recover from the crisis:

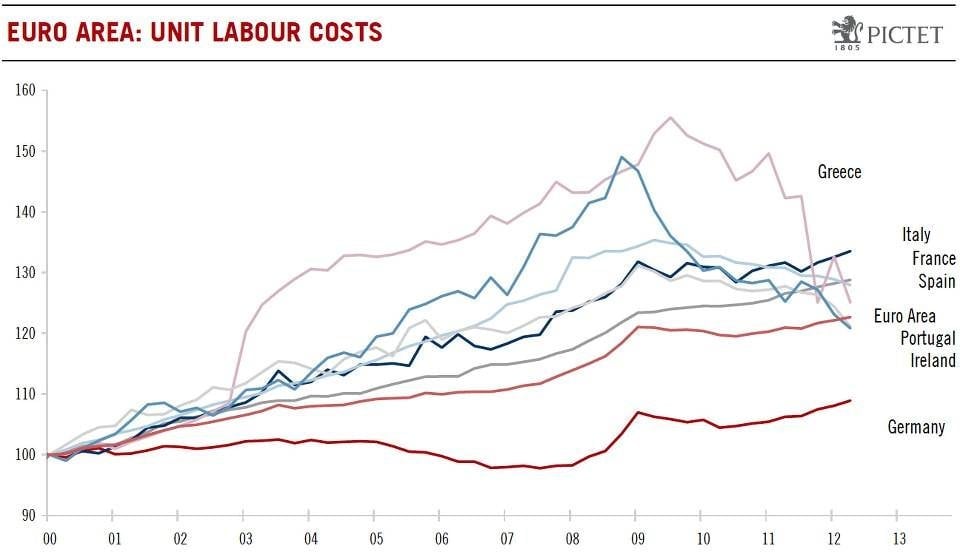

Here’s the underlying problem, though: Italy is not competitive. This chart shows how its labor costs stack up against the larger euro area’s. Since costs in Greece collapsed, Italy’s are now higher, relative to the year 2000, than any other country’s. (Note in particular where Germany is.)

Austerity hasn’t fixed the high labor costs. Of course, if Italy weren’t in a monetary union, it would stimulate its manufacturing by debasing its currency. But cheap credit would only stave off these fundamental problems for so long. Here’s The Guardian’s summary of Italy’s problems:

[E]conomists say much more needs to be done to effect the kind of deep and lasting change needed to get Italy growing again. They focus on Italy’s lack of competitiveness; its untapped labour market resources – women and young people; a thorough reform of product markets and of crucial institutions such as the justice and education systems. Only once these have been properly tackled, they say, will Italy be in a position to capitalise on its strengths….

On top of that, corruption and the gummed-up Italian legal system make Italy’s business climate closer to that of Greece. The International Finance Corporation and the World Bank ranked Italy 73 out of 185, just ahead of Greece’s 78 (Spain, by comparison, came in at 44, while Germany scored 20). Add to that the northern-southern economic divide, and the resurgence of organized crime in the south and you have a pretty awful outlook for the country.

There is good news, though. Italy doesn’t have a massive housing supply overhang or mortgage debt, the way Spain does. The bailout of many of its banks minimizes the threat of a financial-sector collapse. It is implementing reform of its pension system and labor market. And it has a solid manufacturing base that’s seen at least a hint of an uptick in exports in the last few months, even as the euro strengthened.

Of course, borrowing costs need to stay down if the country is to keep working toward economic growth. The election results—and the outlook for a coalition—make the risk of soaring interest rates chillingly real. But loose credit can only act as the economy’s stabilizer for so long. And the economic, social and political reform that Italy needs to undergo to escape of its own “lost decade” will need credible, competent leadership just as much.