America is full of buildings named for people who were horribly racist. What should we do about it?

It’s hard to walk through Princeton University’s picturesque New Jersey campus without passing a tribute to former US president Woodrow Wilson, an alumnus and favorite son.

It’s hard to walk through Princeton University’s picturesque New Jersey campus without passing a tribute to former US president Woodrow Wilson, an alumnus and favorite son.

Students live and study in Woodrow Wilson College, where a mural of the grinning ex-president covers a wall in the dining hall. Not far away rise the modernist columns of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

This week, the university’s Board of Trustees will begin taking comment from university students, alumni, faculty and staff on whether it’s time to take down some or all of these symbols of Wilson. Addressing the former president’s legacy was a primary demand of protestors who occupied Princeton’s Nassau Hall last month.

The demonstrations at Princeton and related protests at the University of Missouri, Yale University, Ithaca College and others are part of a nationwide movement demanding redress of the US’s legacy of racial injustice on college campuses and beyond.

In the Wilson case, it’s also about challenging the narrative of the past that America allows itself to remember.

Tributes and memorials don’t rise on their own as dispassionate records of history. They are created by people making specific comments about their values. And the things a culture obscures or refuses to recognize say as much about its ideals as the things they do.

The power of symbols

Wilson, the 28th US president and a president of Princeton, was celebrated for much of the 20th century for progressive policies like the creation of the Federal Reserve System and his championing of the post-World War I League of Nations.

He was also racist, even by the standards of the time in which he lived. In both Princeton and in Washington, Wilson used his power to actively pursue an agenda of white supremacy: barring black students from admission, purging African-American employees from the federal government.

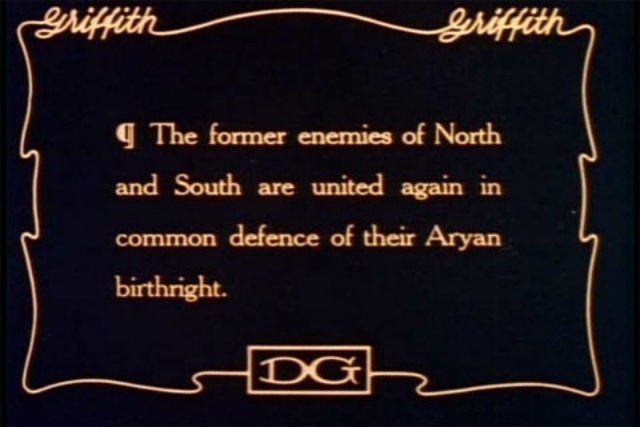

He screened in the White House The Birth of a Nation, the 1915 silent film celebrating the fictionalized origins of the Ku Klux Klan. Director D.W. Griffith used quotes from Wilson’s own academic writing in its subtitles.

“It is like writing history with lightning,” Wilson said admiringly afterward, “and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

But memorials and monuments—named buildings, statues, historical markers—say a lot more about the people who erect them than the people they commemorate.

The Wilson school was christened in 1948, 24 years after the ex-president’s death and before the Civil Rights Era.

This debate at Princeton is less about Wilson’s presidential record than it is about the decision to honor him and the values it implies.

“Every historic site is a tale of two eras. It’s a tale of what its about, and it’s a tale of when it went up,” said James W. Loewen, a historian and author of the books Lies My Teacher Told Me and Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. “Sometimes a monument has nothing accurate to tell us about what it’s about. They always have something to tell us about when they went up.”

A selective history

Take, for example, Kentucky’s Civil War monuments. Kentucky was a slave state but never seceded from the Union. It sent 90,000 troops to the Union army and 35,000 to the Confederacy, according to Loewen’s research in Lies Across America.

Today, Kentucky’s Confederate monuments outnumber memorials to the Union by more than four to one. Most of those markers went up between 1890 and 1940, decades after the Civil War’s end, during a period Loewen calls the “nadir” of US white supremacy. (Wilson’s presidency was smack in the middle of that, from 1913 to 1921.)

The selective history of the US landscape rankles all the more in contrast to the dearth of physical markers acknowledging the history of people of color.

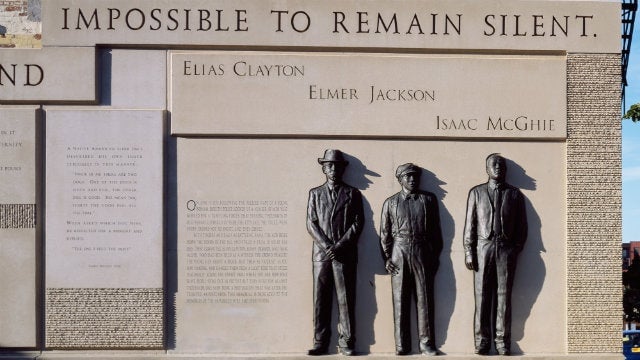

“If a community thinks something is significant, you represent it through monuments, memorials,” Equal Justice Initiative executive director Bryan Stevenson told Quartz. “To not talk about the legacy of slavery, of lynching . . . says something really significant about our failure to confront the history of racial inequality.”

There is, rightly, a national museum dedicated to the Holocaust. There is no national museum comprehensively detailing the experience of 450,000 Africans kidnapped and forcibly transported to the US and the subsequent millions born into slavery. (The Smithsonian will open the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall next year, but its remit is broad, and slavery is only a part of its collection.)

A memorial and museum to the roughly 3,000 people killed on Sept. 11, 2001 opened 10 years after the terror attacks. Between 1877 and 1950—that nadir period of racial oppression—almost 4,000 black Americans were lynched by their countrymen. Hardly any public monuments mark their lives or the campaign of terror that claimed them. Many of those murders occurred on the lawns of county courthouses adorned with Confederate memorials.

To rectify that imbalance, the Montgomery, Alabama-based EJI has erected three markers at lynching sites, with plans to put up 25 more next year.

This collective refusal to see the violence inflicted upon black Americans has been central to Black Lives Matter and the new civil rights movement. A society that can’t or won’t look at its full history will continue to make decisions based on inaccurate and incomplete information.

“Woodrow Wilson is pretty far down on my list of people I’m interested in challenging,” Stevenson said. “But it doesn’t mean that if you understand our history, that you would make some of the choices that have been made” about which names get the mythologized treatment.

Rethinking our heroes

Lionizing individuals is tricky. People and the times they live in are complicated, imperfect, multi-dimensional affairs. This isn’t just an old white man problem. Women’s rights and birth control champion Margaret Sanger was enthralled by the potential of eugenics. Mohandas Gandhi was a misogynist who wrote loathingly of women.

Their contributions to society were real and significant. Wilson profoundly changed America’s approach to foreign policy and domestic progressivism. These accomplishments should not be erased from history, and no one is seriously arguing that they should be.

But to highlight one facet of a legacy while rendering its others invisible, to mythologize at the expense of the truth, perpetrates the original injustice. It does a disservice to history, and to all of us who have to make sense of the present using the record of the past.

The final decision on Wilson’s legacy has been left with the Board of Trustees. The board is recruiting input from scholars on Wilson’s legacy, and is holding meetings this spring to hear testimony from students, alumni, faculty and staff.

If Wilson’s name stays on the buildings at Princeton, the laudatory, “Wilsonic temple” approach to his legacy should be rethought. As today’s students are often reminded, universities are places to be confronted with uncomfortable truths.

One of those may be that the US has been capable of choosing presidents willing to openly repress Americans based on the color of their skin, and that subsequent generations have found this unremarkable enough to overlook when inscribing them into history.