The ingredients of Harlem’s renaissance are captured in this new film

Alvin Starks gestured broadly as he spoke. He was standing in a gallery space in Harlem at the Schomburg Center, a research unit of the New York Public Library. Starks is the Director of Strategic Initiatives for the Schomburg, the leading research facility devoted to black culture. “The Schomburg is trying to take its material… and put it out,” he said, turning his palms outward and extending his arms, with a wide smile. “That’s a huge goal for us.” Nearby, a group of schoolchildren took in the current exhibition, neatly demonstrating the value of communicating what the Schomburg has to offer, whether it is physically held in the stacks or in the minds of its top-shelf curators.

SPONSOR CONTENT BY CITI

Alvin Starks gestured broadly as he spoke. He was standing in a gallery space in Harlem at the Schomburg Center, a research unit of the New York Public Library. Starks is the Director of Strategic Initiatives for the Schomburg, the leading research facility devoted to black culture. “The Schomburg is trying to take its material… and put it out,” he said, turning his palms outward and extending his arms, with a wide smile. “That’s a huge goal for us.” Nearby, a group of schoolchildren took in the current exhibition, neatly demonstrating the value of communicating what the Schomburg has to offer, whether it is physically held in the stacks or in the minds of its top-shelf curators.

For Starks, Harlem on My Plate, a delicious documentary co-produced by Sonia Armstead and Rochelle Brown, is a perfect embodiment of a project that is fulfilling that goal of showcasing the Schomburg’s resources. With the help of Citi, which is also providing crucial funding for an ambitious renovation of the Schomburg Center, Armstead and Brown drew heavily on the resources of the Schomburg to take a deep dive into the culinary past and present of Harlem, a neighborhood at the heart of black life in America. For Starks, the way the film connects food culture and the research center is fitting. He noted that Arturo Schomburg himself, the scholar who gave the institution its name, collected cookbooks and viewed chefs as every bit the artists that writers and painters are—“the poets and the cooks were one” to him, Starks said.

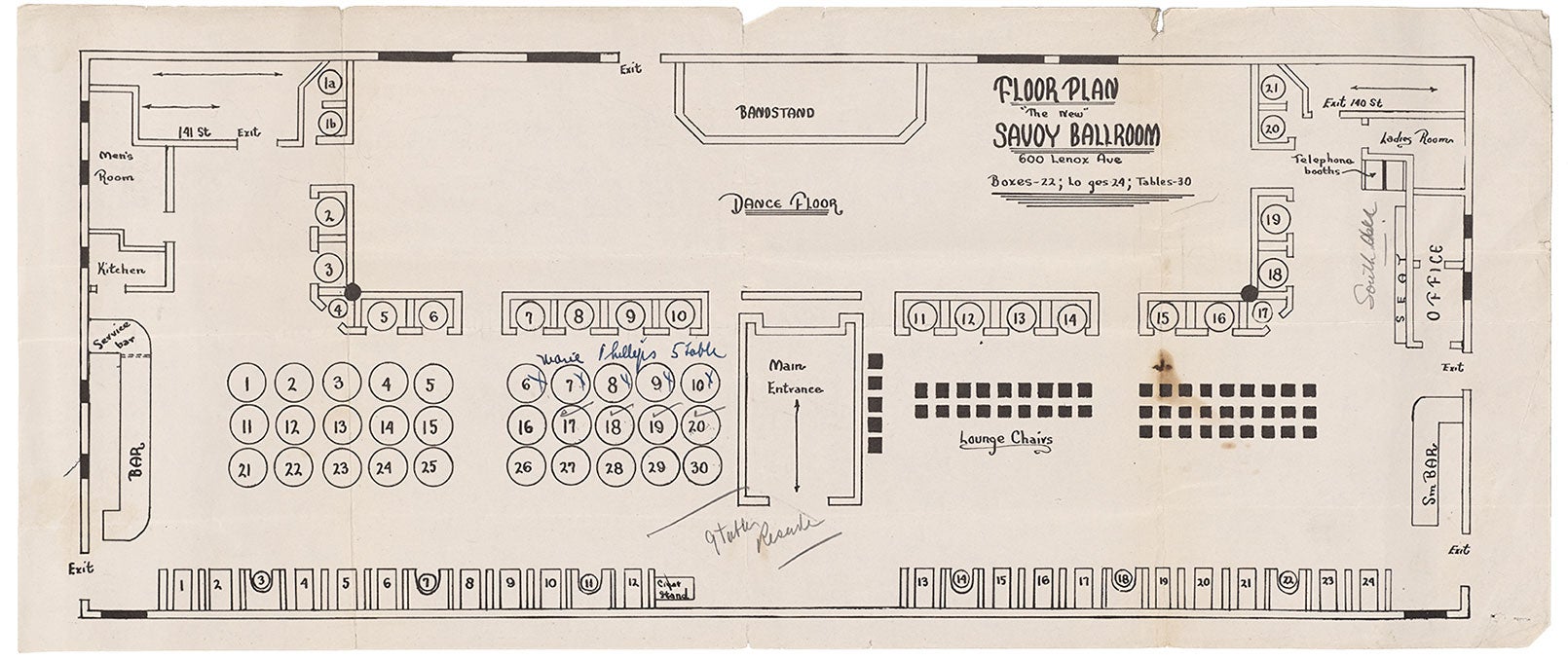

Commandeering a conference room for an intensive eight-week residency of a kind, the filmmakers and the company they founded, Powerhouse Productions, fully tapped into the expertise and knowledge of the center’s staff. The librarians took a lot of pleasure, Starks noted, in doing what they do best: sharing information. They pulled catalogs and archival boxes and maps and gave their hard-earned advice. Armstead and Brown were already deeply experienced in film productions related to food but still found themselves learning new things at every turn. “We were really being educated along the way,” Armstead said.

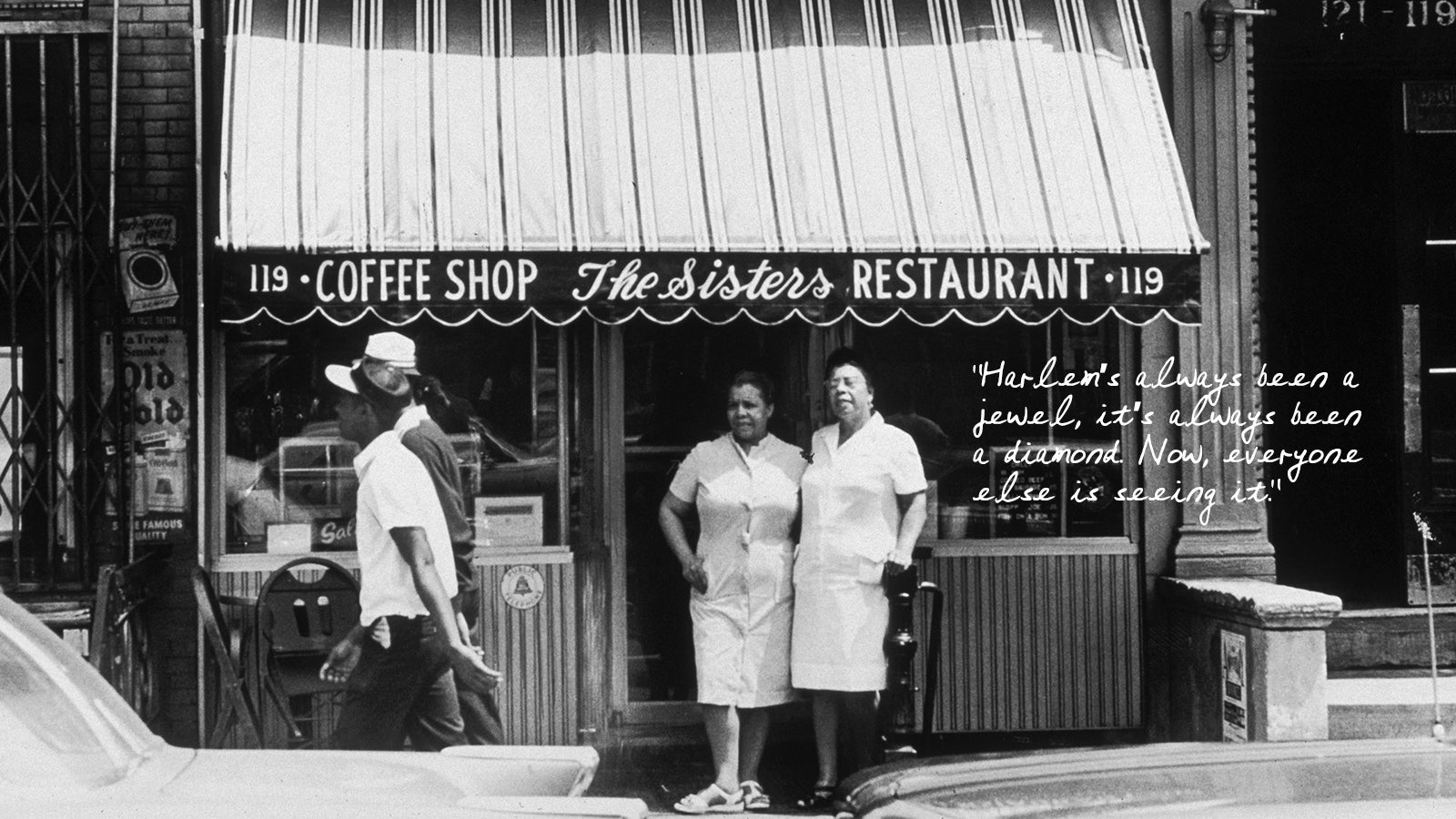

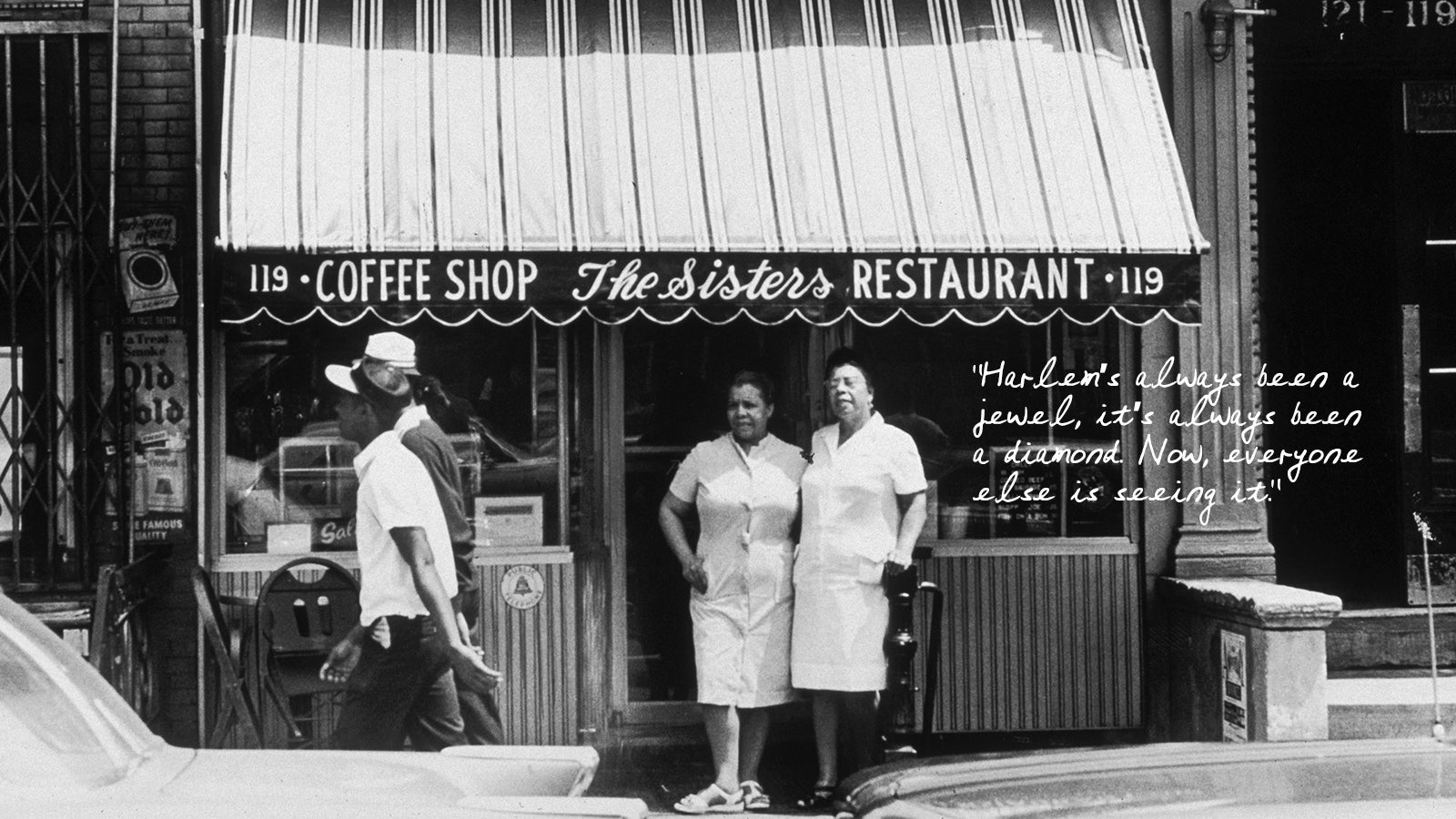

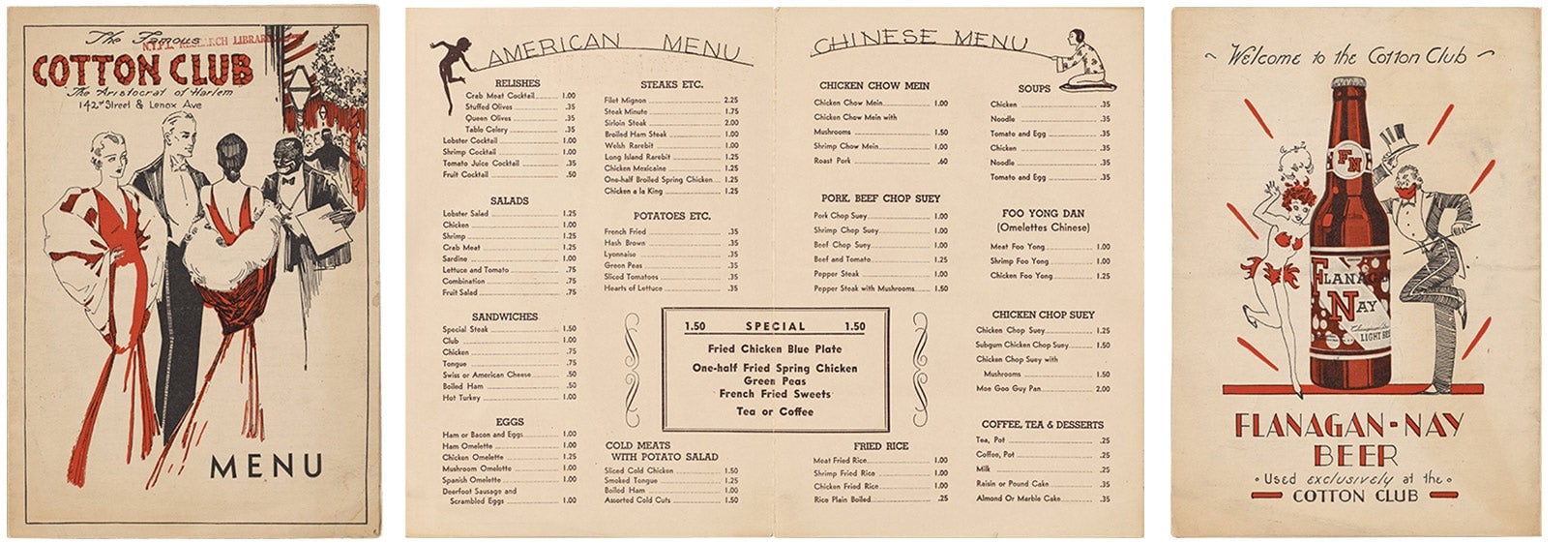

When the co-producers leafed through the Schomburg’s midcentury menus from the Cotton Club, boxer Joe Louis’s Bar & Restaurant, and other iconic Harlem spots, they felt the thrill of literally touching history. (They were surprised to find pages devoted to Chinese food—at about a dollar a dish.) Schomburg materials that supply crucial texture to the film also include black and white photographs of significant eateries and nightclubs, since departed, and archival footage of Harlem and its restaurants of yore. Collectively they show, as Armstead pointed out, that “going out to eat was an experience,” a significant moment to savor and celebrate.

The Powerhouse team journeyed outside the walls of the Schomburg as well, running with an idea and taking it beyond what anyone at Citi or the Schomburg had envisioned. They filmed in restaurants and on the neighborhood streets and interviewed culinary luminaries of the past and present.

They were capturing Harlem at an opportune moment, with the area in the midst of a boom. Melba Wilson, former employee of the iconic Sylvia’s and now owner of Melba’s, says in the film, “Harlem’s always been a jewel, it’s always been a diamond. Now, everyone else is seeing it.”

But culinary culture reflects much more than economic growth. “Food is birth, and it’s death—it’s everything,” Armstead said. Clearly infected with her enthusiasm, Starks chimed in: “Food is part of people’s collective memory.”

With Harlem on My Plate, Armstead and Brown are not only tapping into that collective memory but documenting it for the future. They found one of several historical goldmines in the form of white-haired Geraldine Griffin, proprietor of the now-defunct Adele’s Kitchen, a soul food go-to for generations. As she recounts in the film, when Harlem fell on hard times, her restaurant would advise customers, “No drugs. This is a food place. I sell chicken, not drugs.” Griffin was deeply grateful to the filmmakers for documenting an establishment and an era that could have slipped into obscurity without an effort to give it new life. “I could die tomorrow,” she told them, touchingly, “and people would know my story.”

At a recent intimate preview screening put on by Citi and Powerhouse, Brown introduced the film with a smile. “We’re good at this. We know how to tell a story. I’m 45 now and we’ve been doing this a while—I can say that.”

The reaction of the crowd to the movie, right from the start, put to rest any doubt that Brown was speaking the truth. Footage of dishes both traditional and inventive produced widespread murmurs of appreciation and appetite, and the remarks of those interviewed brought the crowd alive. Rep. Charlie Rangel, who has served as Harlem’s US Congressman for a quarter century, scored the biggest laugh when he impishly expressed the joys of champagne and chitlins.

Alvin Starks said of the Schomburg, “Harlem on My Plate really made us look internally. It led to a lot of self-discovery.” The project has been such a success, he felt, that the staff began to think about how else they could showcase the work of the center for generations to come.

The trailer for Harlem on My Plate, from Powerhouse Productions.

Harlem on My Plate is now hitting the festival circuit, where audiences in other cities are recognizing that it really tells a national story. The life of the film is only just beginning; it will be held in perpetuity at the Schomburg Center. At the preview screening, scholars and artists and library users from across the spectrum experienced the film themselves, just as future viewers will. Surely some minds were wondering what else might be accomplished with the resources of the Schomburg Center as it moves into a new era, with financial assistance from Citi. As the lights came up to vigorous applause, a sense of possibility rippled through the crowd.

Read more about how innovative financing is driving progress here.

This article was produced on behalf of Citi by the Quartz marketing team and not by the Quartz editorial staff.