The offshore gas bonanza Israel was counting on might never materialize

Tel Aviv, Israel

Tel Aviv, Israel

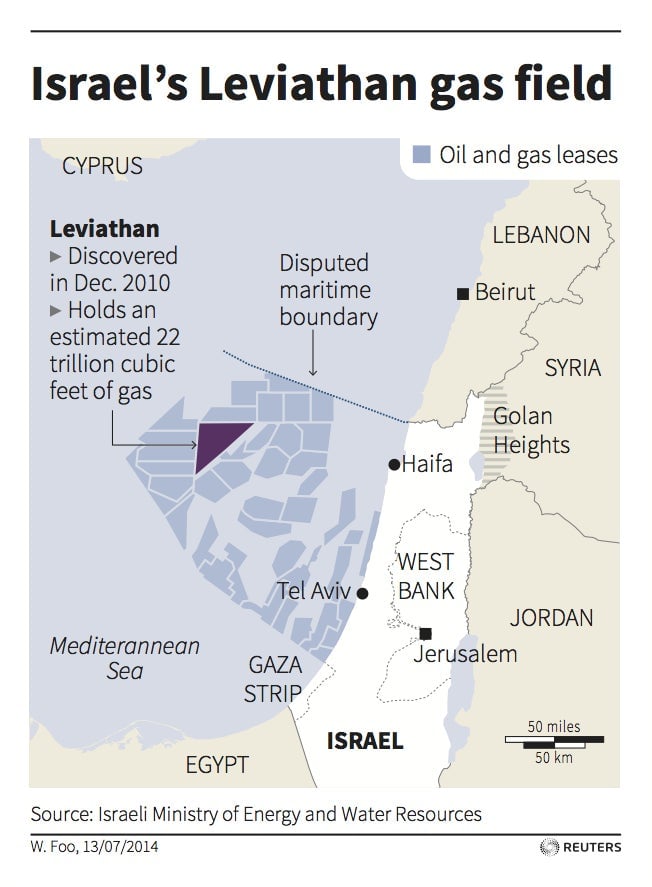

In 2010, Israel discovered a large natural gas off-shore reserve. Dubbed Leviathan, it was supposed to be a game-changer for the country. Five years later, it’s no longer looking like a sure bet.

In theory, cheap energy from the gas field could boost the economy and provide enough power generation for decades. Tens of billions of dollars in royalties and tax revenue could pad public coffers.

Most critically, according to prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu, Leviathan has enough gas to yield Israel’s first-ever energy export deals—offsetting the state’s increasing isolation over its reluctance to hold comprehensive peace talks with the Palestinians. ”Our ability to export gas enhances the strength of the state of Israel… It makes Israel much more resilient to international pressures,” he recently told the Knesset’s economics committee.

To that end, Netanyahu and his top aides have traced out a regional energy alliance in which Israeli gas would become a linchpin knitting together an arc of so-called moderates spanning from Amman to Athens. This vision involves Israel exporting gas to Egypt and then on to Europe, as well as a pipeline to transport Israeli and Cypriot gas to Greece. Providing gas to Europe might defuse efforts to boycott goods from West Bank settlements, according to Netanyahu’s advisors. Meanwhile, looking east, Israeli exports to Jordan would bolster the Hashemite Kingdom’s energy shortfall, and block efforts by Iran to become Jordan’s supplier.

“A new Middle East of energy,” joked Alon Liel, a former diplomat, who likened the government’s plan to the half-baked Israeli visions for regional economic interdependence that were floated in the 1990s, at the height of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

But the fate of Leviathan now looks hazy. Though the gas field’s developers, Houston’s Noble Energy and Israel’s Delek Group, signed a tentative deal last year to supply $30 billion worth of gas to liquefaction facilities in Egypt, the prospects of that happening seemed to recede last week. On Dec. 6, hours after an international arbitration court awarded Israel’s electric utility $1.7 billion for a cut-off in Egyptian gas exports that followed the fall of president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, Cairo announced a freeze of negotiations over sending Israeli gas to Egypt. The discovery of a massive gas reserve off the coast of Egypt this past summer also makes Israeli gas less of a long-term necessity.

Turkey could have been a customer for Israeli gas—some argue it’s still the best bet—but after five years of political estrangement between the former close allies, it’s looking like a long shot.

Leviathan is estimated to have 470 billion cubic meters (16.6 trillion cubic feet) of gas. Together with Tamar, a natural gas field discovered in 2009 which has 300 BCM, the two reserves are thought to be enough to supply Israel for nearly 40 years. Tamar was rushed in to production to ease a shortage after the supply cut from Egypt in 2011.

But without a big export deal, officials, executives and analysts say there’s a chance Leviathan may remain untapped. ”You need to show where the money is going to come from—a contract for 15 to 20 years. Nothing short of that will produce the credit to finance” development of Leviathan, said a former Israeli gas executive who asked to remain anonymous. ”Absent an anchor client… we are not going to have exports. For the moment we are stuck.”

In addition, Netanyahu’s government is facing a political headache over the regulatory framework for the gas deal.

The 36-page arrangement, approved by the Knesset in September, formalizes a pricing mechanism, deadlines for developing Leviathan, and pre-requisites for exporting Israeli gas. But it hands Delek and Noble Energy a monopoly that would be exempt to government price oversight. Street protests have accused Netanyahu of signing away control over a public resource to the corporations. Israel’s Electricity Authority warned that the arrangement could cost the economy nearly $2 billion in overpriced electricity bills over 15 years. The antitrust commissioner (who later resigned) ruled that the framework would establish a powerful monopoly that could gorge consumers. Netanyahu responded by invoking an obscure legal clause that allows an override of antitrust rulings on national-security grounds. Opponents are preparing to challenge him (link in Hebrew) in the country’s supreme court.

The companies involved are frustrated too. Griping about government foot-dragging and shifting regulatory requirements, Noble and Delek have warned they’ll abandon Leviathan if the government tries to reopen the terms of the gas deal. Regulatory delays on Leviathan have also put a damper on investment in exploration in Israel’s other offshore gas concessions.

If the gas from Leviathan stays in the ground, the government could lose up to $2.4 billion in tax revenue by 2022, according to an estimate by the finance ministry. There’s also the problem of energy security: Israel would have to find a source for imports instead of relying solely on the Tamar field, which currently supplies half of Israel’s energy.

Though Netanyahu and the gas companies blame the delays on calls for more regulation, Amir Mor, who runs the Israeli consultancy EcoEnergy, says Israel lost valuable time because the government itself didn’t make developing gas regulations a priority.

“I hope Israel didn’t lose the window of opportunity to export gas to Egypt,” Mor said. “We’ll be smarter in the next few months.”