The five questions universities should use to reckon with their racist legacies

Wander around the stunning grounds of Princeton University, through the quads and past mock-Tudor Gothic buildings, and you might be fooled into believing that you are in Oxford, England. Their appearance is not all the two universities have in common.

Wander around the stunning grounds of Princeton University, through the quads and past mock-Tudor Gothic buildings, and you might be fooled into believing that you are in Oxford, England. Their appearance is not all the two universities have in common.

Both were built on the backs of generous donations and bequests from rich and powerful white men. And in the past month, student protesters at both universities have made headlines for similar reasons.

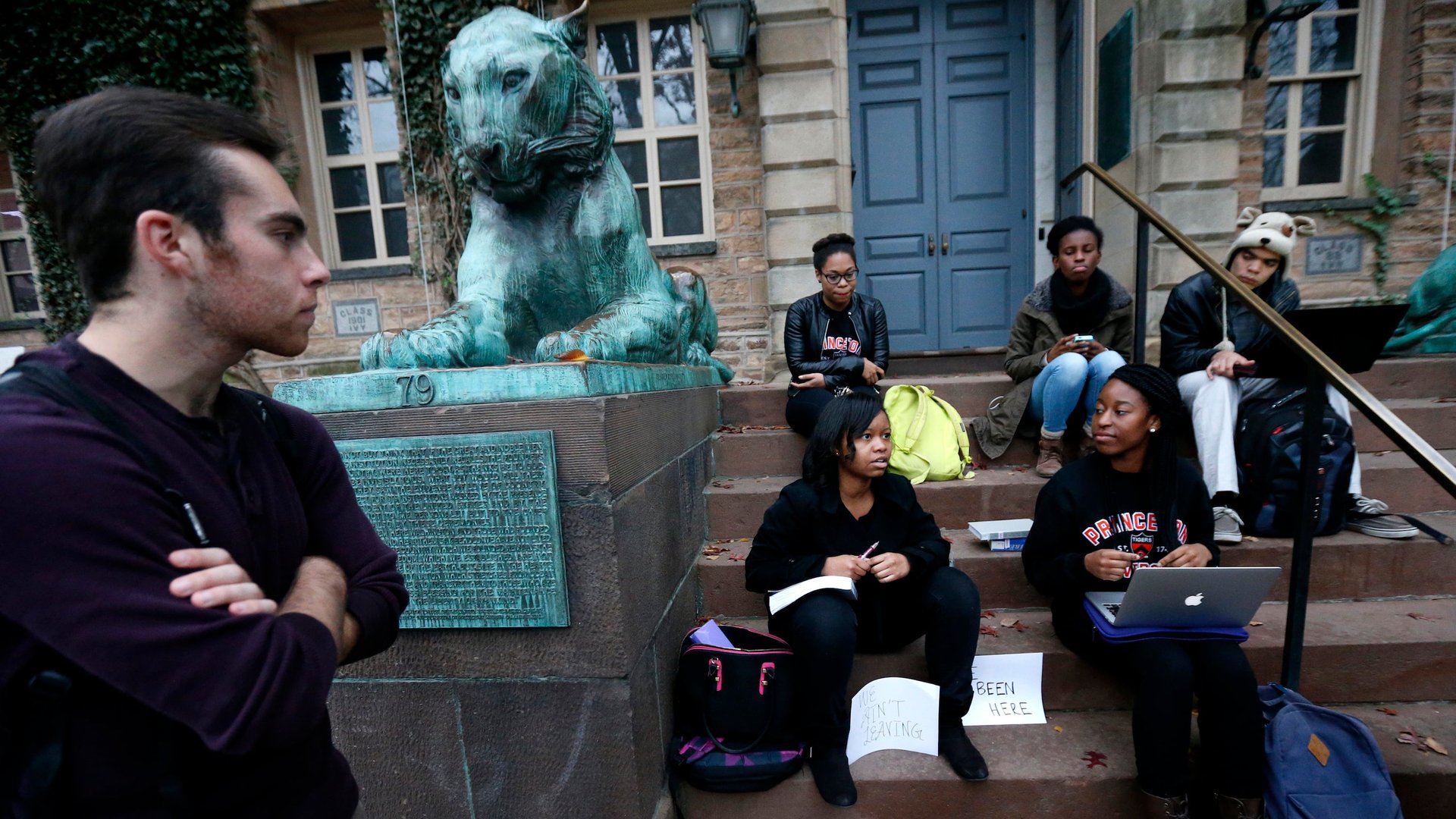

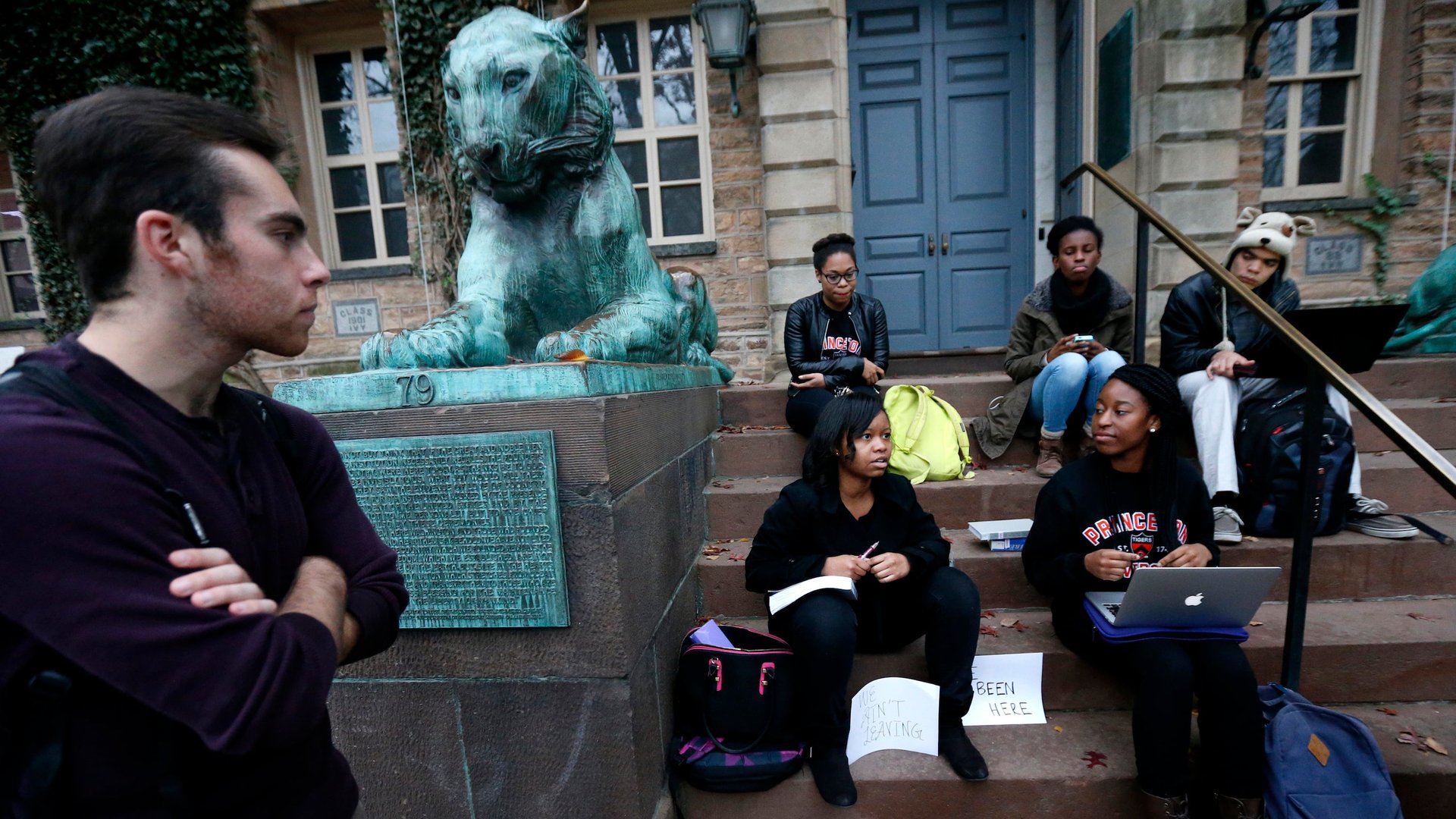

Students at Princeton are demanding that the name “Wilson” be removed from Wilson College—a residential complex—and from the internationally renowned Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Wilson was president of Princeton before he became the 28th president of the US. He was also a racist. His values, demonstrators say, are not in keeping with today’s Princeton.

An almost identical protest has taken place at Oriel College in Oxford, where there’s a campaign to remove a statute of Cecil Rhodes. Rhodes attended the college and left a significant sum of money to the college upon his death in 1902. He was, of course, a potent force in the promotion and expansion of British colonialism.

Authorities at both Oxford and Princeton say they are considering the demands. So how should they respond?

It’s important to note that moral values evolve—and, we hope, progress—over time. It is therefore inevitable that the vast majority of historical figures held views that we deem offensive today. But while it would be impractical (not to mention expensive) to remove the names of every rich, famous and powerful man with problematic views, there are circumstances under which it might be the right thing to do.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of considerations to take into account when determining whether historical figures should have their names or images stripped away.

- Were the views of the person in question commonly held at the time? If so, he is not as blameworthy as he would be if his opinions were widely regarded as offensive even during his lifetime. Of relevance here is the consistency of the historical figure’s opinions. He should be regarded more leniently if, say, he changed his mind about his early, wild misogyny than if his nasty outlook continued throughout his life.

- What were the consequences of the person’s views? Obviously, it is less serious if the offensive opinions were held in private and never acted upon than if they were central to his ideology, motivated many of his actions and damaged numerous lives.

- How does the objectionable aspect of the person mesh with his other attitudes and accomplishments? For example, it may be that a given historical figure was a dreadful bigot in one area, but progressive in many others.

- How strongly do people feel about the historical figure? By this I do not mean just the degree of offense felt by those having regularly to walk past, say, a statute of Rhodes—important though this is. I also mean the opposite. If a historical figure is widely venerated, it may be that to remove his name would provoke a backlash that reinforces the very values that the protesters want to undermine.

- What is the financial cost of the de-honoring? We might decide that the symbolic significance of removing a name is not worth tens of thousands of dollars – and that the money could be more productively spent in other ways.

These considerations can’t be inputted into a straightforward algorithm. But at one extreme, it’s clear that the Heinrich Himmler School of Diplomacy would be inappropriate, whilst the Orwell Prize can be left as it is. The Orwell Prize, named after George Orwell, is a prestigious British award for political writing. Orwell, the record shows, held anti-Semitic views (depressingly common in the first half of the 20th century). But he was an outstanding writer, an unblinking opponent of totalitarianism, and a searing critic of social injustice.

If universities reflect on the points sketched out above and decide that removing a historical figure’s name or image cannot be justified, this need not be the end of the discussion. It is a simple step to add a plaque distancing an institution from some of the more repugnant views of a long-dead patron.

Similar debates are bound to crop up again. Universities, in their desperate and often-grubby attempts to raise funds, have developed the habit of plastering benefactor names in every available space, from laboratories and lecture halls to corridors and benches. Some of the characters they accept money from already have dubious reputations. But because none of us is perfect, and because most of us hold opinions that our descendants will disapprove of, de-honoring controversies will never go away.

Just imagine what future generations will think of the Trump Tower.