Interior design junkie Adolf Hitler invented the modern politician’s at-home interview

With the current barrage of political grandstanding in the US, it can be refreshing to see politicians looking unguarded, once in a while. It’s not by accident that US Republican presidential contender Donald Trump opened his gilded Manhattan triplex and lavish upstate New York estate for the current US Weekly (Feb. 8) issue. The Clintons have hosted Oprah in their Chappaqua residence, while George W. Bush and John Kerry have graced the covers of Ladies Home Journal.

With the current barrage of political grandstanding in the US, it can be refreshing to see politicians looking unguarded, once in a while. It’s not by accident that US Republican presidential contender Donald Trump opened his gilded Manhattan triplex and lavish upstate New York estate for the current US Weekly (Feb. 8) issue. The Clintons have hosted Oprah in their Chappaqua residence, while George W. Bush and John Kerry have graced the covers of Ladies Home Journal.

Being seen relaxing at home can warm up anyone’s public image. Opening their doors to the press was a tactic that Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and his wife Asma famously deployed in 2011, when they allowed themselves to be photographed playing with their children on their kitchen floor. After the Assad regime was accused of human rights atrocities months later, Vogue magazine tried in vain to scrub the Internet of its glowing family profile.

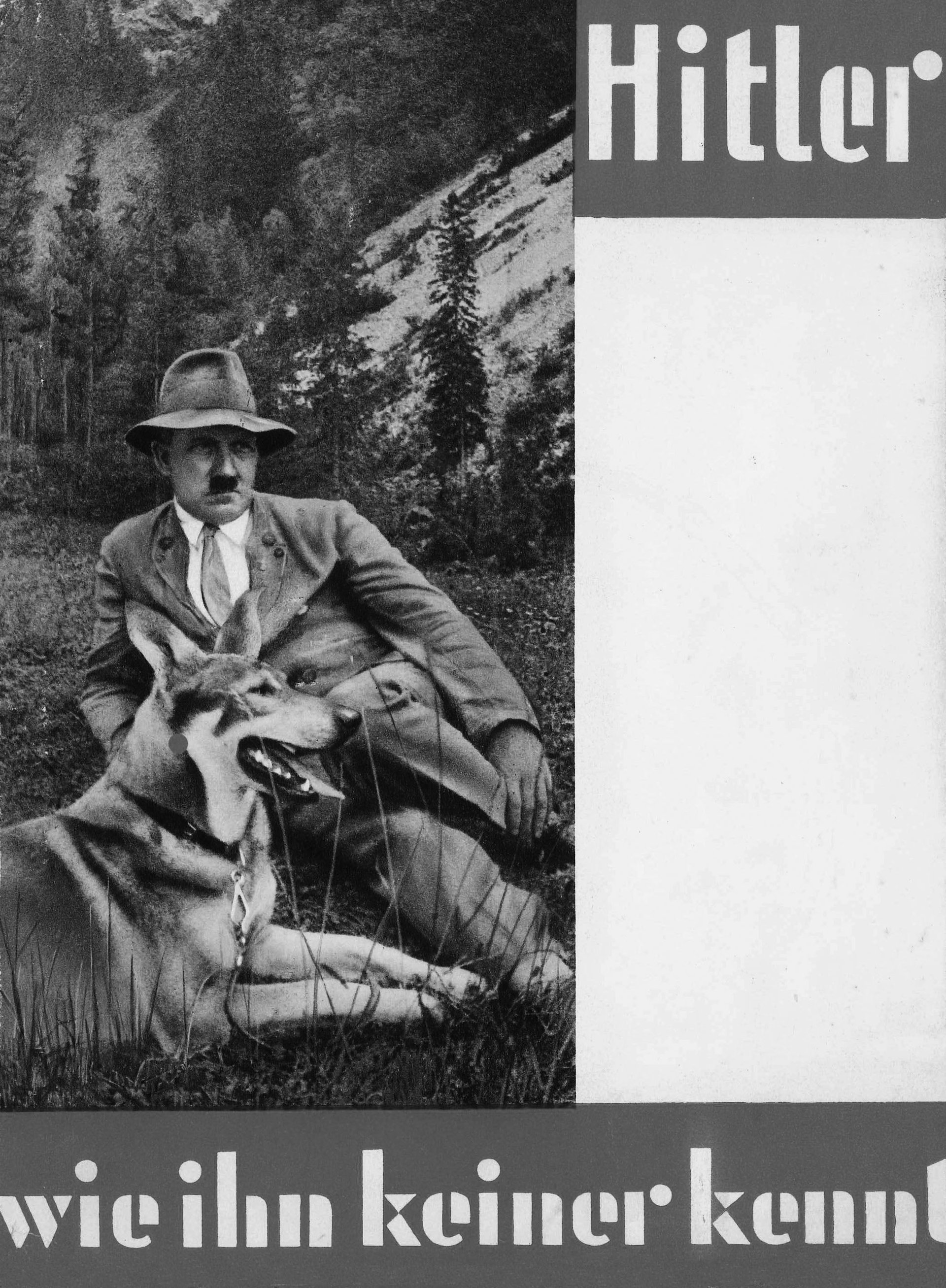

Readers and writers alike are easily enchanted by the idea of meeting a powerful leader in their private residence. But the origin of this PR tactic is sobering, as architecture historian Despina Stratigakos explains in her provocative new book, Hitler at Home.

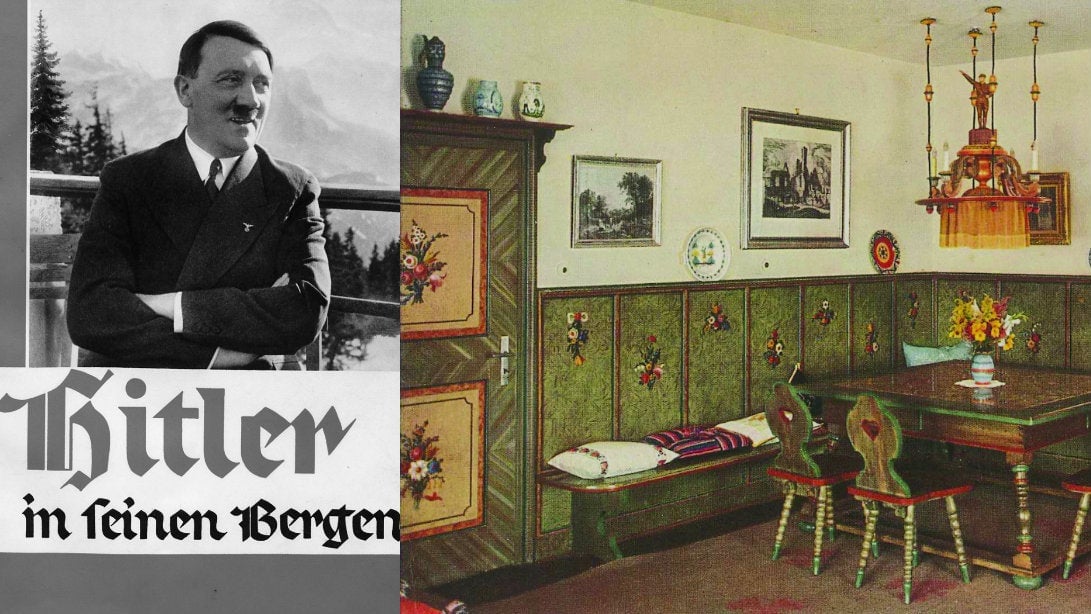

“Today it’s almost normal for politicians to trot out their personal lives but it wasn’t [the case] when Hitler was doing it,” she tells Quartz. Just before the outbreak of World War II, the New York Times Magazine published a long, favorable article about Hitler’s “unobtrusively elegant” Berghof mountain retreat, Stratigakos reminds us. The dreamy title of that 1939 piece: Herr Hitler: At Home in the Clouds.

Although daunting, totalitarian architecture is typically associated with the Nazi aesthetic, Stratigakos posits that images of Hitler’s domestic life, framed by tasteful interiors, had an equally indelible effect on the public imagination. And in this realm, there was perhaps no one more influential than a woman named Gerdy Troost.

Hitler’s favorite interior designer

The creative partner and wife of one of Hitler’s most cherished architects, Gerdy Troost defined and defended the Nazi propaganda aesthetic until she died in 2003. Troost worked on the renovation of Hitler’s homes and transformed the Prince Carl Palace in Munich to an urbane apartment for state visitors (notably for its first guest Italian dictator Benito Mussolini). Later, she even handcrafted jewel-encrusted medal boxes for the regime.

Troost was Hitler’s favorite tastemaker, and his trusted counsel in matters of design and architecture. But despite her 15-year collaboration with the German dictator, Troost’s name has been relegated to a footnote in history books, observes Stratigakos.

While many scholars tend to disassociate Hitler’s private domain from his politics, Stratigakos believes that there was no separation in the Nazi’s relentless propaganda machine. In fact, Hitler’s tranquil, designer homes provided the backdrop to his most effective portraits—these, says Stratigakos, helped him move on from the ”screaming reactionary” reputation he once cultivated in the 1930s.

Drawing on sealed personal papers at the Bavarian State Library in Munich, Stratigakos’s remarkable volume (released on Sept 2015) is the first to limn the extent of Troost’s influence on the Nazi head of state.

Troost and Hitler’s design teamwork

Raised as a pacifist and with a curiosity for modern art that Hitler rejected, Troost was initially skeptical of the politician who came to see her husband so frequently. But a few weeks after their first meeting in Sept 1930, Troost was head-over-heels for Hitler’s charisma. “Contrary to the unappealing hue and cry of his public persona, Hitler in person…behaves like a truly splendid, serious, cultivated chap,” she wrote to her mother.

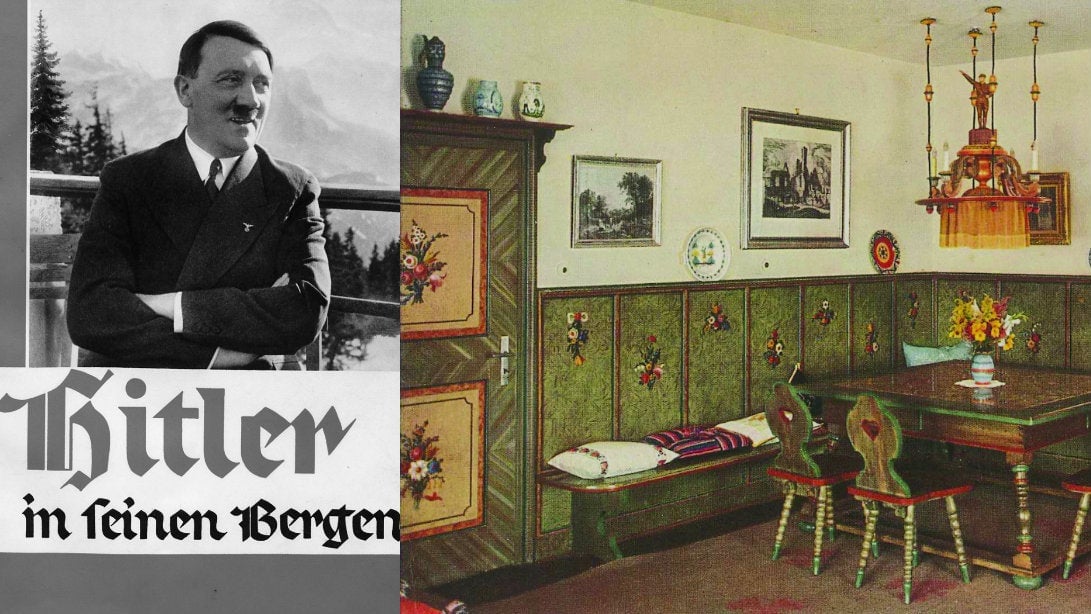

After her husband’s death in 1934, the two remained such good friends that Hitler’s German Shepherd Blondi and Troost’s German Shepherd Herras were even paired to mate.

In the impeccable homes that Troost created for him, Hitler readily welcomed cameras. Carefully orchestrated photo shoots showed him laughing with friends, stopping to greet children, cavorting with dogs, and he’s even shown feeding baby deer.

For the perfect backdrop to these staged vignettes, Troost paired traditional, neoclassical architecture with quiet, subtle color harmonies—a counterpoint to the bombastic, swastika-branded venues Hitler was usually photographed in. Through these warm and fuzzy “domestic performances,” as Stratigakos puts it, the world was shown a softer side of the Third Reich.

Stratigakos connects Hitler’s strange and strategic obsession with home makeovers with his rise to power. After his niece committed suicide at their shared apartment in 1931, Hitler, then a budget-conscious bachelor and the leader of the nation’s second-most powerful party, became concerned that the scandal would thrust his modest abode into the spotlight.

Throughout the rest of his reign, he worked with closely with architects and designers to change his image from rabble-rouser to a refined intellectual.

A cautionary tale

The woman who designed Hitler’s personal makeover was not an easy subject for Stratigakos, a self-described feminist historian—and the daughter of a someone who lived through the brutal Nazi occupation in Greece. Among the many achievements in Stratigakos’ groundbreaking research about Troost is that she’s able to paint a full picture of such a divisive character.

“It was very, very tough, writing about her and ‘living with her,’ as you do with your subject,” she tells Quartz. “But what I hoped to show was her complexity.”

Stratigakos suggests that unmasking the design aspect of Hitler’s onetime appeal offers a cautionary tale, today.

“It was important for me to make readers reflect about their own consumption,” she explains referring to our lust for tabloid stories about the inner lives of famous people. “As a historian, my primary responsibility is to show how things work ideologically but I also wanted to show how we can be seduced by our own desires.