The most innovative global businesses will help drive sustainable development

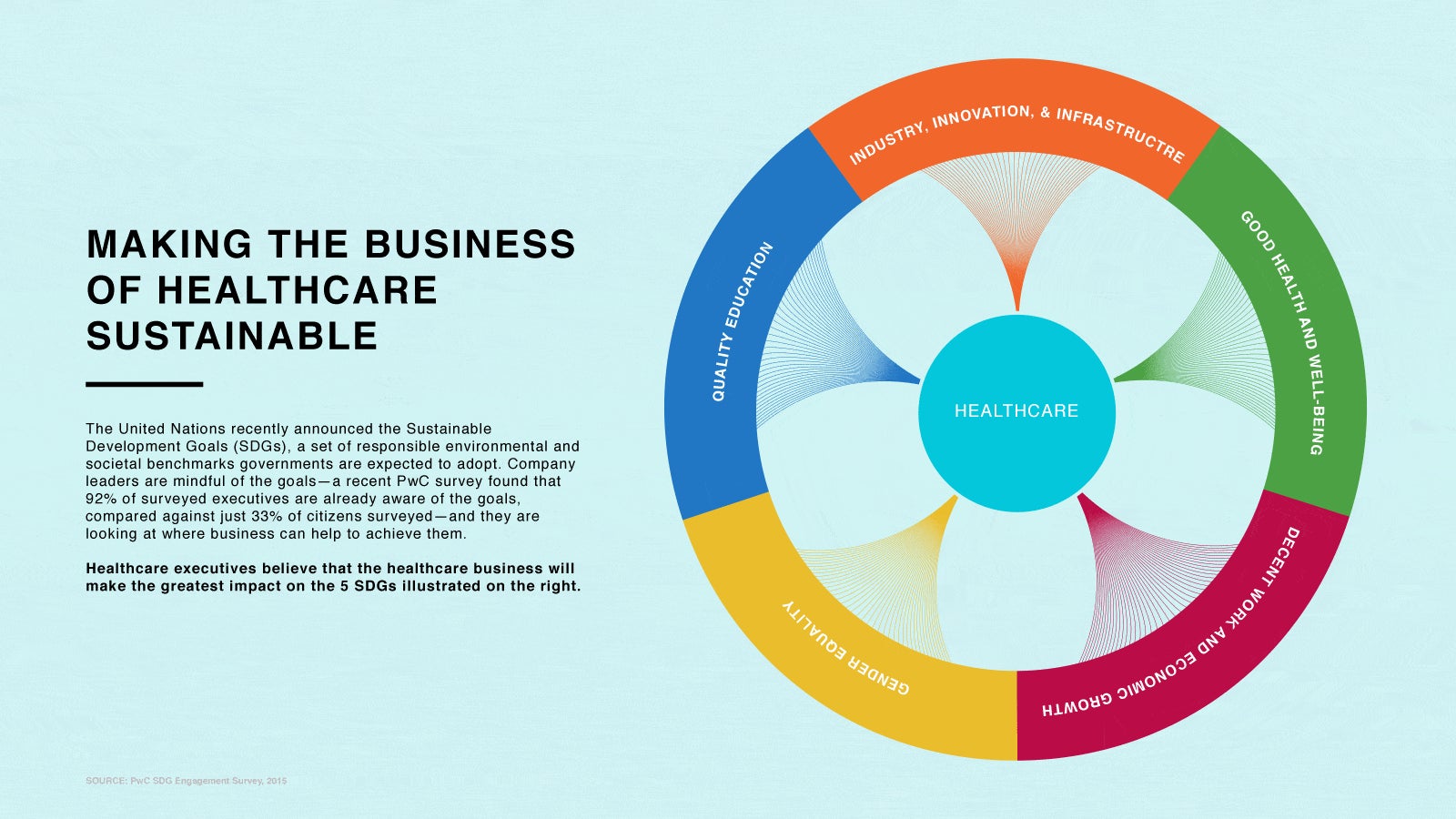

(See the infographic enlarged.)

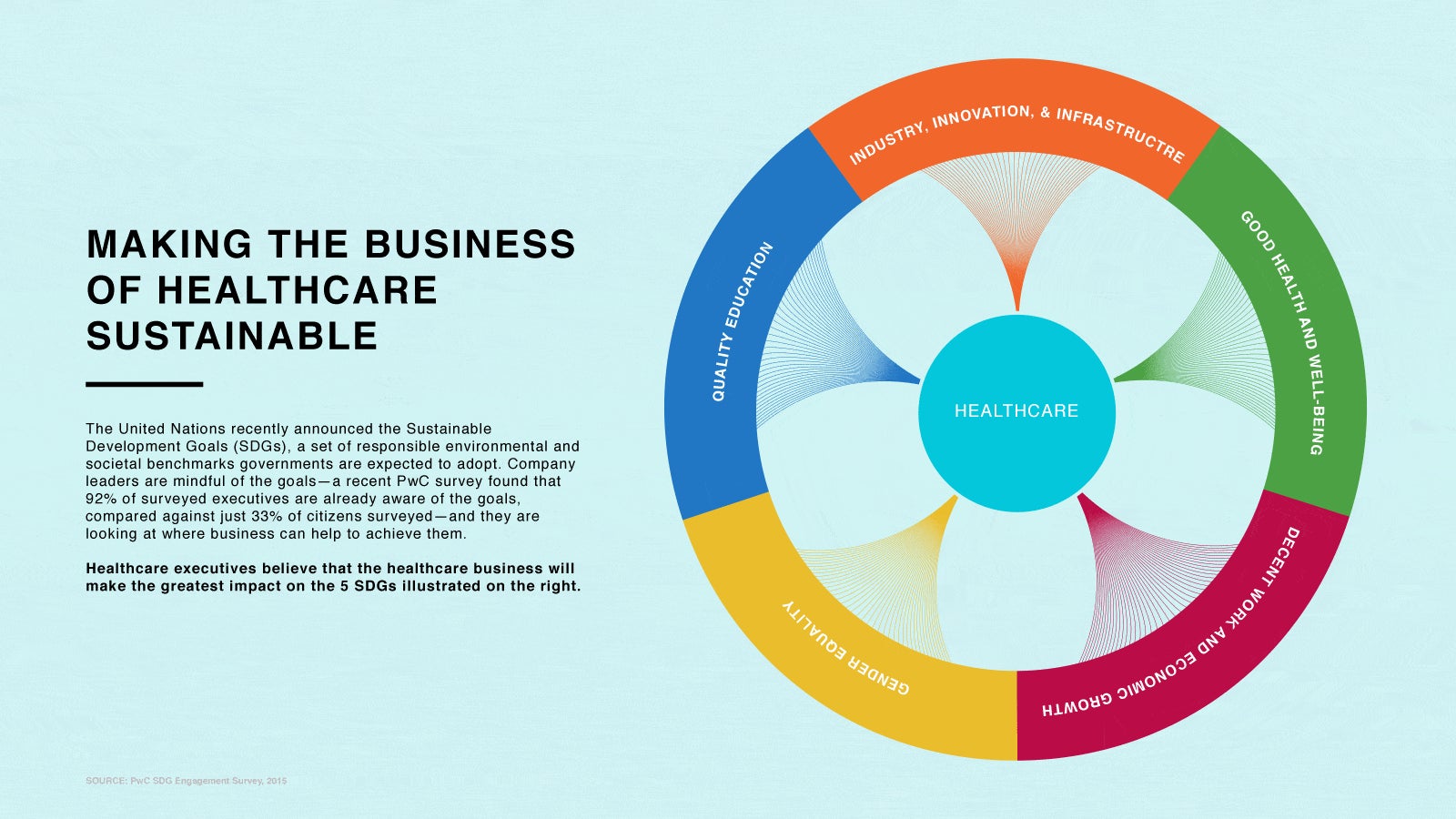

(See the infographic enlarged.)

Recently, the UN officially adopted a new global framework for development goals. Since 2000, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have set the benchmarks for progress on key indicators across national governments and civil society. For the most part, they’ve been effective. Look at the improvement in reducing child mortality: the number of deaths of children under age 5 fell from 12.7 million in 1990 to 6.3 million in 2013. And HIV infections are slowing, declining by 38% between 2001 and 2013.

That kind of progress is encouraging. But the MDGs were largely viewed as measures for developing nations—burgeoning economies or poorer countries—that didn’t necessarily present an opportunity for business to participate in. That changes with the newly enshrined Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): by focusing on issues that will help shape the future of sustainable enterprise—like smart economic growth, efficient trade, and skilled employment—the new framework was constructed in hopes that global multinationals will play a more significant role.

“The post-2015 development agenda presents a historic opportunity for businesses to engage more deeply as a strong and positive influence on society,” said Peter Bakker, President & CEO of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, in a PwC report on the SDGs.

Thanks to decades of hyper-globalization, the hopes and fates of citizens, businesses, and governments have become increasingly intertwined. And multinational corporations’ ability to deliver impact at scale will be crucial to advancing progress. In that respect, perhaps there has never been a time when the joint ambitions of public and private entities meant more to successful development.

That sentiment rings particularly true for healthcare. Even with MDG progress in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and other emerging markets, affordable healthcare solutions that focus on primary and preventative care treatment are still in need.

One multinational, General Electric, is looking to get ahead of the SDGs. GE has a history of partnering with health ministries, private providers and NGOs to help build out the infrastructure and skills needed to scale up care facilities. But the recent announcement of a $300 million investment in high-value, low-cost medical technologies in India, South Asia, Africa and Southeast Asia is further recognition that partnering on development projects in emerging healthcare systems is good business.

Terri Bresenham, CEO of GE Healthcare’s new Sustainable Healthcare Solutions (SHS)—the group responsible for shepherding that investment—sees her group’s business aligning with the SDGs: “Globally there are 5.8 billion people estimated to have little to no access to healthcare. Our first hand experience in India and South Asia, where GE has a Healthcare Innovation Center, commercial sales and service activities and our Global Research Center, has allowed us to work across the ecosystem and better understand the numerous challenges that face healthcare providers in developing countries.”

She goes on to describe the need for public-private cooperation in order to expand access: “Healthcare deliverers, for example, won’t simply accept a box of standard equipment from us.” And innovation in both products and business models is a key part of that, she mentions, “They’ve made it clear that we need to look right and left of equipment and understand all the issues that both they and their patients need solved in order for a better outcome.”

Bresenham has plenty of experience with emerging market care systems. Originally hired as a biomedical engineer right out of university, she’s led GE’s healthcare efforts in South Asia for the last four years and has seen the challenges of scaling up, firsthand. She says SHS will need to be nimble to improve health outcomes and can look to startups for inspiration.

“The ‘Lean Startup’ model lets us rapidly test new ideas that can lead to more affordable technologies, products and services to maximize effectiveness for customers before we scale up,” Bresenham said. “It’s kind of the best of both worlds as we can combine that nimbleness with GE’s technical capabilities, scale, and our partners’ expertise to tackle these complex, structural healthcare challenges.”

With an estimated shortage of 2.4 million doctors, nurses and midwives across the globe, and a paucity of data about where health shortages are most acutely felt, those challenges are daunting. But Bresenham is optimistic: “If we can achieve just one of the sustainable development goals, it would make a huge impact. However, I believe that GE’s SHS has the potential of achieving a lot more.”

This article was produced on behalf of GE by the Quartz marketing team and not by the Quartz editorial staff.