Louis Vuitton: The humble origins of the world’s most coveted and copied luxury brand

Louis Vuitton’s rise as today’s top luxury brand began at place much like a contemporary pack-and-ship facility. As the new exhibition Volez, Voguez, Voyagez in Paris demonstrates, the brand’s fame started with handmade traveler’s boxes and cases.

Louis Vuitton’s rise as today’s top luxury brand began at place much like a contemporary pack-and-ship facility. As the new exhibition Volez, Voguez, Voyagez in Paris demonstrates, the brand’s fame started with handmade traveler’s boxes and cases.

On display at beginning of the nine-room showcase at the Grand Palais is the company’s first breakthrough product: an unadorned, perfectly rectangular grey trunk. After observing that the traveling trunk’s traditionally domed lid made it unwieldy to stack and transport, founder Louis Vuitton introduced a flat-top model, engineering an airtight box made of lightweight material and covering it in his signature grey canvas. Before Vuitton’s design innovation in 1858, the trunks’ curved domes were thought necessary to repel water that might otherwise seep in when loaded in the cargo of ships or trains.

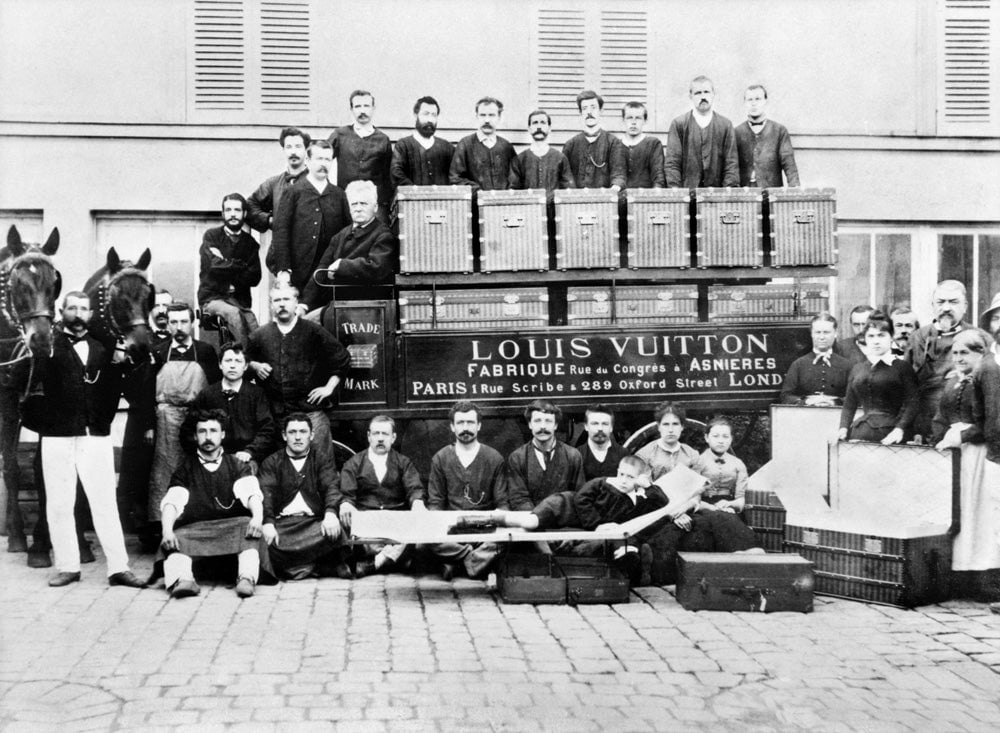

Orphaned at an early age, Vuitton started working as a packer and box-maker at the workshop of Romain Maréchal in Paris, at the age of 16. Using carpentry skills picked up doing odd jobs along his long trek (by foot) from his hometown in the Jura region to the French capital, Vuitton flourished as a maker of custom-designed wood boxes that housed anything from mirrors, clocks, flowers, paintings, to “ladies trimmings.” When he opened his own shop—Louis Vuitton Malletier—in 1854, he marketed himself as a specialist packer for discerning travelers seeking a professional who “safely packs the most fragile of objects.”

His service was in high demand by travelers eager to explore newly established shipping and train routes at the time, and his business boomed after the empress of France, Eugenie de Montijo, appointed Vuitton as her personal packer and trunk-maker.

Vuitton’s vertical steamer trunks were particularly popular. Designed like portable pieces of furniture equipped with drawers, compartments, and hangers, they allowed travelers to transport their wardrobes without needing to unpack.

Cases for all occasions

Before it made popular handbags styles like the doctor’s bag-shaped Speedy, or the capacious Neverfull, produced in its factories in France, US, Spain, Germany, and Italy, Louis Vuitton’s metier was made-to-order trunks and cases.

From a round, oversized chauffeur’s case to house a spare tire and a change of clothes, to a handsome tea service set ordered by the Maharaja de Baroda, among the most fascinating objects in the exhibit are the one-of-a-kind Vuitton leather-clad branded boxes specially designed to conform to the needs of their clients. For the traveling reader who didn’t want to delay progress on Proust’s lengthy opus In Search of Lost Time, Vuitton made a small, monogram leather box to house all the volumes of the world’s longest novel.

Today, the brand’s special-order atelier, located in the former Vuitton family residence in Asnières-sur-Seine, is run by Vuitton’s great-great-grandson, Patrick. It is the only production factory under the direct stewardship by a member of the Vuitton clan. To this day, one can still order any kind of case to fulfill any conceivable need or whimsy, even a small box to house your child’s baby teeth like one customer requested—anything but an exact replica of an existing Louis Vuitton case, an exhibition docent told Quartz.

Anti-counterfeit monogram

Copycats and counterfeiters have plagued the Louis Vuitton brand through much of its 161-year history.

Vuitton’s groundbreaking flat-top travel trunk—the template for the modern luggage—became such a coveted status symbol in Victorian-era circles that many of his competitors began to copy his design. As an anti-counterfeiting measure, Vuitton introduced new patterns to distinguish his trunks: a stripped canvas called Rayée, followed by a checkered pattern called Damier. The iconic LV monogram with the Japanese-style flowers and quatrefoils was introduced in 1896, four years after Vuitton passed away. Created by his son Georges, who took over the business, the custom step-and-repeat geometric motif was meant to be the brand’s most unique and distinguishing pattern.

Ironically enough, the monogram pattern has become one of the most replicated branding insignias today—from cheap iPhone cases to waffle makers to body tattoos—as a graphic shortcut for luxury and wealth.

The World Customs Organisation ranks Louis Vuitton as the sixth-most counterfeited brand in the world, but with the availability of fake Louies in so many markets and street vendors worldwide, including peddlers online, it would seem much higher. For discerning but budget-strapped buyers, there are even classes of replica Louie Vuitton with the “most authentic fakes,” (aka Class A bags) commanding higher prices.

LVMH, Louis Vuitton’s parent company, is aggressive about cracking down on trademark violators and counterfeiters, as well as their outlets, like eBay. To protect its brand equity, valued at $28.1 billion, the company earmarks €15 million annually for its robust legal department, according to Forbes.

Conceivably, a tenth room exploring the counterfeiting phenomena so core to the brand from the start could have elevated curator Olivier Saillard’s excellently staged exhibition from a worthwhile, yet unsurprising, showroom experience to one that explores Louis Vuitton’s rooted cultural resonance across economic and ethnic boundaries.