The day of the year you’re most likely to die a natural death

The depressing realization that all New Year’s resolutions have already been abandoned is far from the worst feature about January 1.

The depressing realization that all New Year’s resolutions have already been abandoned is far from the worst feature about January 1.

It just so happens that the first day of every year is also the deadliest.

Various studies have shown that self-harm, homicides, and car accidents spike on New Year’s Day. But in 2010, UC San Diego sociology professor David Phillips investigated whether the date itself was a risk factor for death. As the Washington Post reports, the answer, unfortunately, is yes—but we still don’t know why.

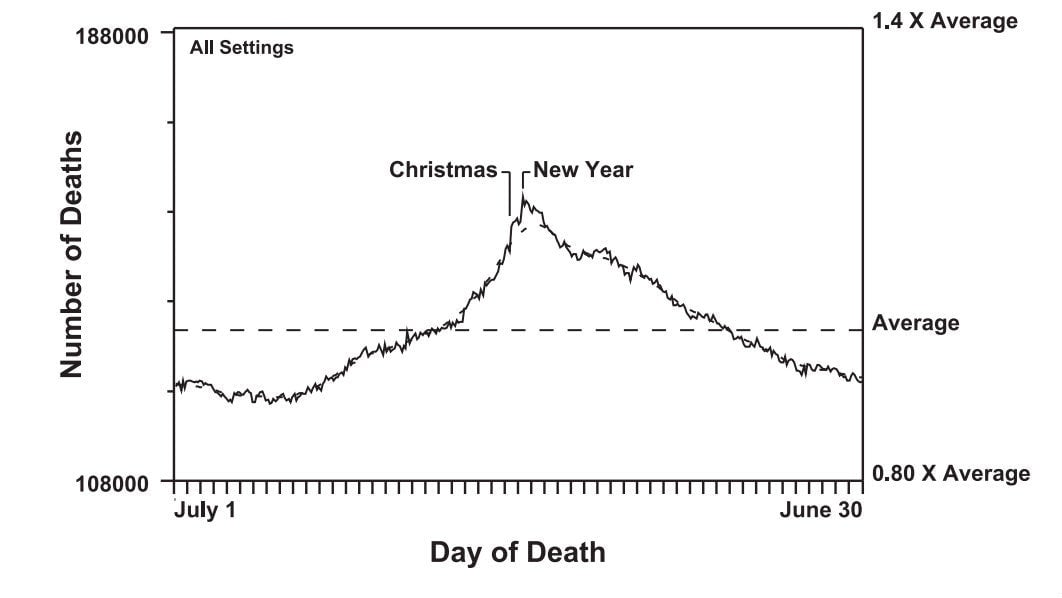

Phillips examined more than 57 million official US death certificates, issued over 25 years from 1979 to 2004, and found that deaths from natural causes peaks on New Year’s Day.

A rise in drink and drug abuse can’t be the cause writes Phillips in his paper, published in the journal Social Science & Medicine, as the mortality spikes aren’t significantly different when you exclude those whose deaths were linked with substance abuse.

Seasonal cold weather and wintry illnesses, such as influenza, can also be disregarded as a cause, as Jan. 1 sees a distinct rise in deaths compared to other equally cold and virus-riddled days in the month.

Phillips examined several other hypotheses and, though some seem more plausible than others, none have enough evidence to fully explain the spike.

Some theorize that people may try to postpone death to reach symbolic events, such as family Christmas festivities or the start of the New Year. However, writes Phillips, there’s no drop in deaths ahead of New Year, which suggests that postponement isn’t particularly successful.

It might be possible that psychological stress shifts suddenly on New Year’s Day. But Phillips says there’s not enough evidence to verify this theory. “We have no nationwide, detailed, rigorous measures of the size, nature, and timing of these putative change,” he writes. “In addition, we know of no unambiguous evidence that heightened psychological stresses can cause abrupt, sharp increases in mortality from a wide range of diseases and for a wide range of demographic groups.”

There is more evidence support the belief that, as medical professionals take time off over the holidays, Emergency Departments are overcrowded, leading to an increase in deaths. Phillips noted a particularly large spike in natural deaths from illnesses that require immediate attention, suggesting that Emergency Department overcrowding could be a contributing factor, as patients are less likely to receive the necessary help. And the spike in New Year’s death has increased over the past 25 years, which correlates with the rise in Emergency Department overcrowding.

But there are other “holiday related-changes in medical care,” writes Phillips. “For example, medical professionals may increasingly suspend work during the holidays and/or patients may increasingly avoid hospital visits during the holidays.”

Phillips tells the Washington Post that some people may ignore serious symptoms over the holidays so that they can spend time with their families, which is a “very foolish thing to do.”

So no matter how much you’re enjoying the countdown to midnight, don’t wait until the clock strikes twelve to get medical help. Some health issues just can’t wait until next year.