Creative people’s brains really do work differently

What makes highly creative people different from the rest of us? In the 1960s, psychologist and creativity researcher Frank X. Barron set about finding out. Barron conducted a series of experiments on some of his generation’s most renowned thinkers in an attempt to isolate the unique spark of creative genius.

What makes highly creative people different from the rest of us? In the 1960s, psychologist and creativity researcher Frank X. Barron set about finding out. Barron conducted a series of experiments on some of his generation’s most renowned thinkers in an attempt to isolate the unique spark of creative genius.

In a historic study, Barron invited a group of high-profile creators—including writers Truman Capote, William Carlos Williams, and Frank O’Connor, along with leading architects, scientists, entrepreneurs, and mathematicians—to spend several days living in a former frat house on the University of California at Berkeley campus. The participants spent time getting to know one another, being observed by researchers, and completing evaluations of their lives, work, and personalities, including tests that aimed to look for signs of mental illness and indicators of creative thinking.

Barron found that, contrary to conventional thought at the time, intelligence had only a modest role in creative thinking. IQ alone could not explain the creative spark.

Instead, the study showed that creativity is informed by a whole host of intellectual, emotional, motivational and moral characteristics. The common traits that people across all creative fields seemed to have in common were an openness to one’s inner life; a preference for complexity and ambiguity; an unusually high tolerance for disorder and disarray; the ability to extract order from chaos; independence; unconventionality; and a willingness to take risks.

Describing this hodgepodge of traits, Barron wrote that the creative genius was “both more primitive and more cultured, more destructive and more constructive, occasionally crazier and yet adamantly saner, than the average person.”

This new way of thinking about creative genius gave rise to some fascinating—and perplexing—contradictions. In a subsequent study of creative writers, Barron and Donald MacKinnon found that the average writer was in the top 15% of the general population on all measures of psychopathology. But strangely enough, they also found that creative writers scored extremely high on all measures of psychological health.

Why? Well, it seemed that creative people were more introspective. This led to increased self-awareness, including a greater familiarity with the darker and more uncomfortable parts of themselves. It may be because they engage with the full spectrum of life—both the dark and the light—that writers score high on some of the characteristics that our society tends to associate with mental illness. Conversely, this same propensity can lead them to become more grounded and self-aware. In openly and boldly confronting themselves and the world, creative-minded people seemed to find an unusual synthesis between healthy and “pathological” behaviors.

Such contradictions may be precisely what gives some people an intense inner drive to create. As psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi said after more than 30 years of observing creative people: “If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it’s complexity. They show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes; instead of being an ‘individual,’ each of them is a ‘multitude.’”

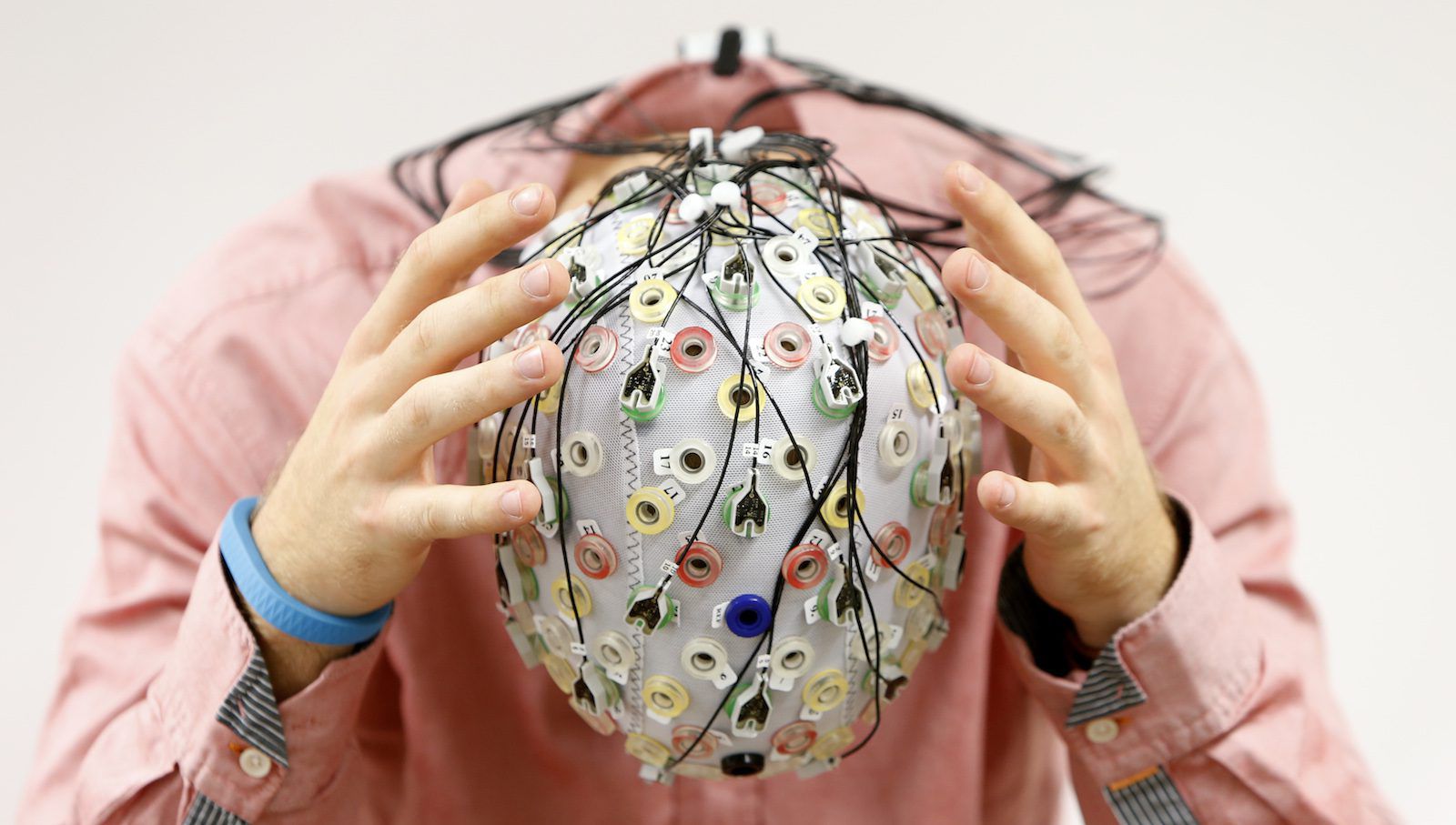

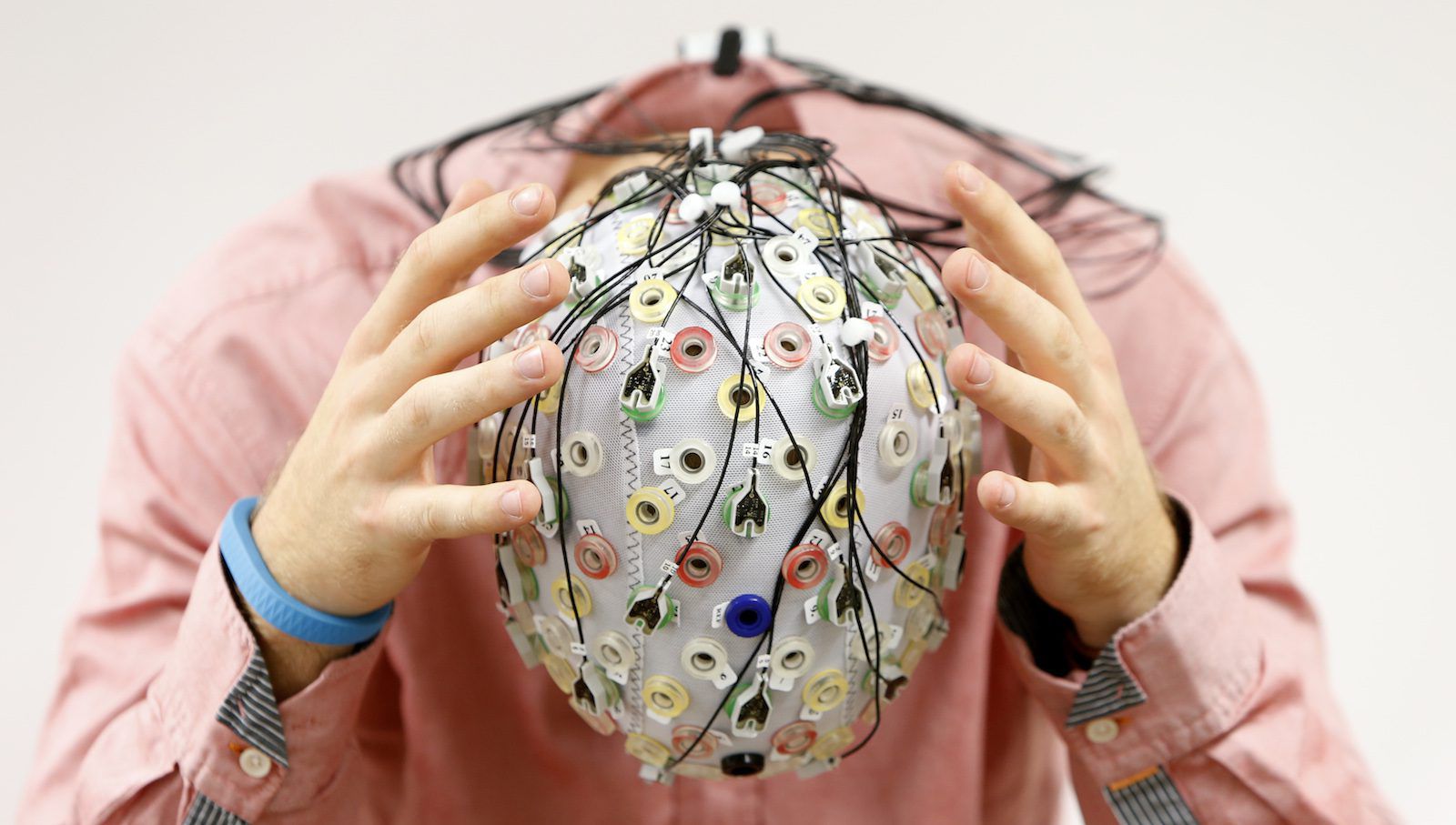

Today, most psychologists agree that creativity is multifaceted in nature. And even on a neurological level, creativity is messy.

Contrary to the “right-brain” myth, creativity doesn’t just involve a single brain region or even a single side of the brain. Instead, the creative process draws on the whole brain. It’s a dynamic interplay of many different brain regions, emotions, and our unconscious and conscious processing systems.

The brain’s default mode network, or as we like to call it, the “imagination network,” is particularly important for creativity. The default mode network, first identified by neurologist Marcus Raichle in 2001, engages many regions on the medial (inside) surface of the brain in the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes.

We spend as much as half our mental lives using this network. It appears to be most active when we’re engaged in what researchers call “self-generated cognition”: daydreaming, ruminating, or otherwise letting our minds wander.

The functions of the imagination network form the core of human experience. Its three main components are personal meaning-making, mental simulation, and perspective taking. This allows us to construct meaning from our experiences, remember the past, think about the future, imagine other people’s perspectives and alternative scenarios, understand stories, and reflect on mental and emotional states—both our own and those of others. The imaginative and social processes associated with this brain network are also critical to developing compassion, as well as the ability to understand ourselves and construct a linear sense of self.

But the imagination network doesn’t work alone. It engages in an intricate dance with the brain’s executive network, which is responsible for controlling our attention and working memory. The executive network helps us focus our imagination, blocking out external distractions and allowing us to tune in to our inner experience.

The creative brain is particularly good at flexibly activating and deactivating these brain networks, which in most people are at odds with each other. In doing so, they are able to juggle seemingly contradictory modes of thought—cognitive and emotional, deliberate and spontaneous. This allows them to draw on a wide range of strengths, characteristics and thinking styles in their work.

Perhaps this is why creative people are so difficult to pin down. In both their creative processes and their brain processes, they bring seemingly contradictory elements together in unusual and unexpected ways.