Masculinity and privilege are killing older white men—no, really

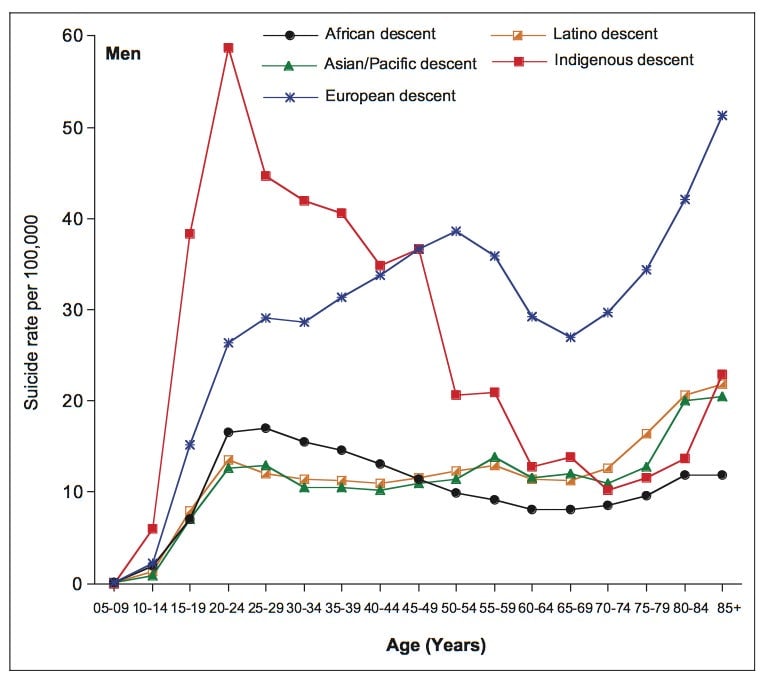

One of the constant findings in suicide studies is that the majority of victims are older white men. Data from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention shows that in 2014, men accounted for 77.4% of all suicides in the US—and white males for about 70%.

One of the constant findings in suicide studies is that the majority of victims are older white men. Data from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention shows that in 2014, men accounted for 77.4% of all suicides in the US—and white males for about 70%.

While most research on suicide has not compared different demographics, a study published in Nov. 2015’s issue of Men and Masculinities Journal by Silvia Sara Canetto, a professor of psychology at Colorado State University does so, with a few interesting findings that might help us understand why older white men (and particularly, those of European origin) are more at risk of suicide than any other demographics.

What is particularly interesting in Canetto’s findings is that the high suicide rates don’t seem to be directly linked with specific life hardships: White older men are less likely to experience widowhood and have better physical health than older women, the report found. Further, they have better financial conditions than both ethnic-minority men and women in general. Nor can depression be considered the determining factor: “medical conditions are just one piece of the story,” Canetto told Quartz, and “depression is as or more common in women,” though they don’t kill themselves as much.

In the paper, Canetto looks at each of the issues that could be blamed for high suicide rates—health conditions, loss, financial hardship—finding that none of them affects older white men more than other demographics. This supports the professor’s theory, which she developed in her years of studying suicide, and through analysis of previous literature: Suicide might be more of a cultural issue than previously accounted for. “There is a signature [to suicide] that is gendered and ethnic,” Canetto told Quartz, noting for instance that the gap between male and female suicides is smaller in Asian cultures.

Older white men belong to a culture that, the professor explained to Quartz, approaches suicide with a “relative permissibility and acceptability.” Further, Canetto found, traits of masculinity are associated with killing oneself; “Surviving a suicide is considered un-masculine,” she explained.

But to worsen the situation for white men is something that affects them at a more individual level, and it’s exactly what worked in their favor for the rest of their lives: privilege. After a lifetime of social privilege (compared to women, or other races), they might not be equipped to suddenly face their own mortality and might resort to suicide more easily than other demographics because of that. “Coping with stereotyping, discrimination or loss may be easier for women or minorities,” said Canetto, since life has likely toughened their skin by the time they reach seniority.

And so, white male privilege works against men too, eventually.

“It’s a cultural phenomenon,” Canetto told Quartz, “therefore it’s amenable to change.”