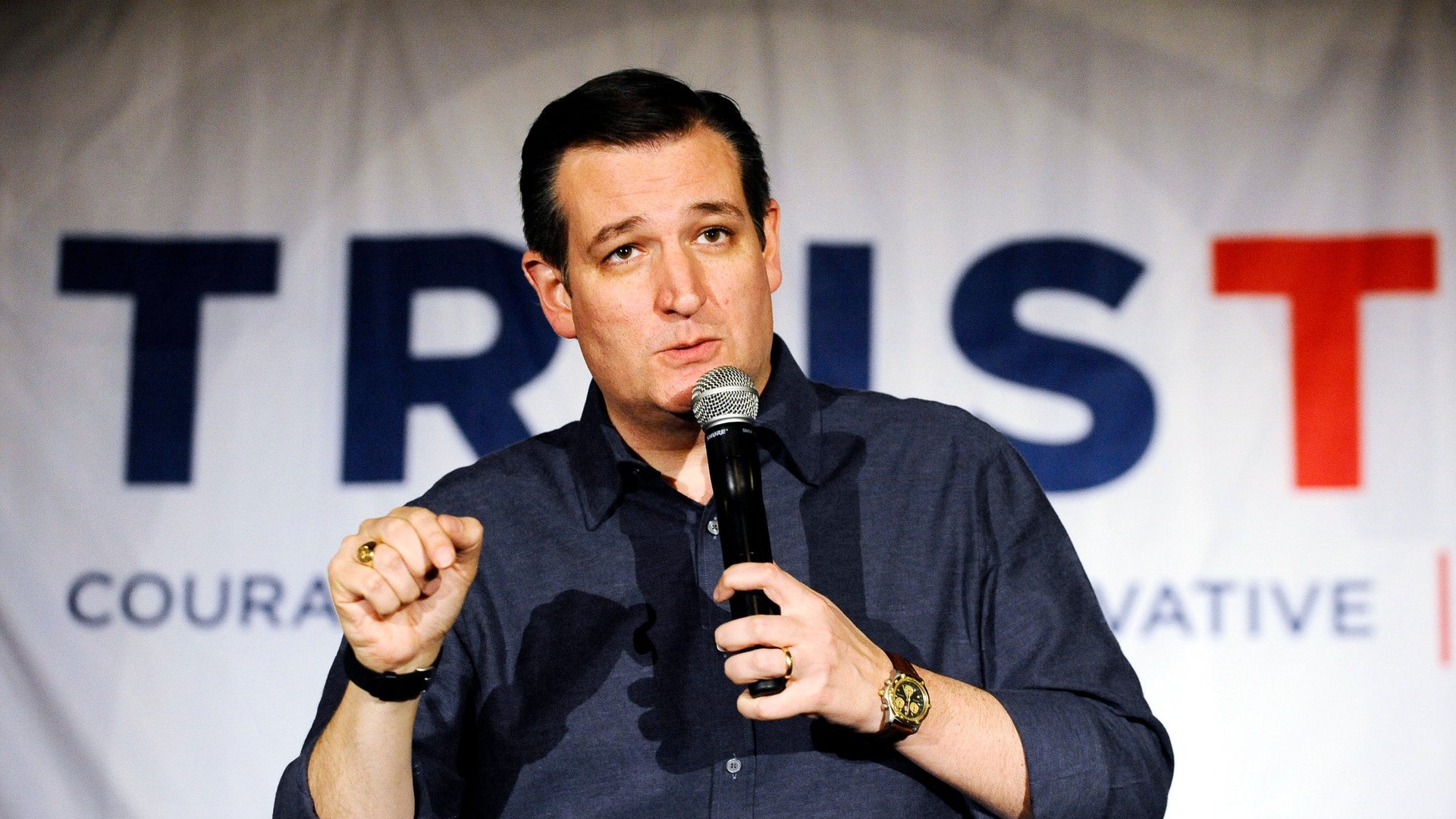

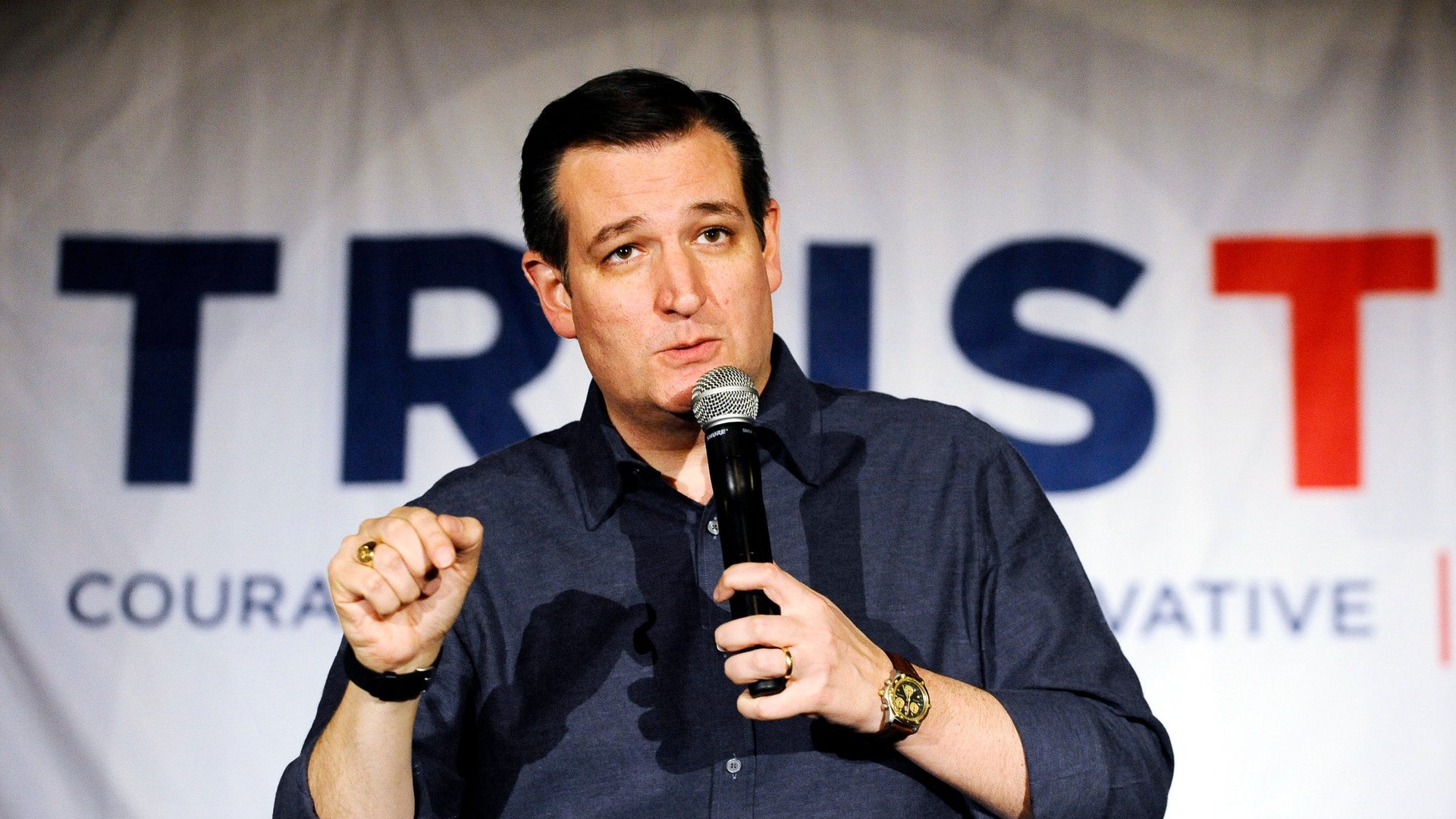

Wall Street critic Ted Cruz funded his senate campaign with a loan from Goldman Sachs

The Tea Party, or however you call the United State’s conservative populist movement, often portrays its origin story as an outraged response to the government bailout of Wall Street during the 2008 financial crisis.

The Tea Party, or however you call the United State’s conservative populist movement, often portrays its origin story as an outraged response to the government bailout of Wall Street during the 2008 financial crisis.

But that rhetoric has never quite jibed with the pro-bank voting record of its representatives. Now the New York Times has revealed that one of the most prominent voices in the movement, Senator-turned-presidential candidate Ted Cruz, received but did not disclose loans of up to $1 million from Goldman Sachs and Citigroup to fund his first Senate campaign in 2012. Receiving the funds is legal. Failing to disclose them to the Federal Election Commission is not.

The real heart of the allegation is that Cruz didn’t disclose the loans because he knew they would conflict with his already strained image as a populist. Cruz, a Princeton and Harvard law graduate whose wife is a long-time employee of Goldman Sachs, isn’t exactly a man of the people. Revealing that New York banks were funding his campaign wouldn’t have helped.

During the campaign, he portrayed his funding as the liquidation of his family’s savings, going all in behind his principles. But the Times’ examinations of financial disclosures released after he was elected to the Senate also show that the family’s assets actually increased during the time period.

As for quid pro quo, it’s worth noting that these loans do not appear to have been given on particularly advantageous terms, for high net worth clients of the bank’s wealth management practice. The Goldman loan was borrowed against the Cruz family’s stock portfolio, a common practice that allows the wealthy to access cash without disturbing their investments.

While Cruz has criticized Wall Street, he also says he would repeal Dodd-Frank, the financial reforms bitterly opposed by the banks. Regardless, Cruz hasn’t had many opportunities to vote on financial regulation in his brief term in office. But his role as a firebrand—holding up votes with procedural objections and egging on conservatives in the House in futile objections to health care reform—may have made it easier for financial sector lobbyists to win key points in the background.

When Cruz and other ultra-conservative members use annual spending bills as a battleground for ideologically charged amendments, members of congress are more focused on excising extremist amendments and avoiding a government shutdown than the construction of the bill itself.

Take the 2014 bill to set government spending, which Cruz delayed in a fight over Obama’s executive orders on immigration. It also reversed a rule in the post-crisis financial regulations that requires banks to “push” financial derivatives out of their federally-insured institutions and into separately capitalized subsidiaries. The rule was designed to make sure that taxpayers aren’t the hook for risky investments and to force banks to fully back their own bets. As such, it was a top target of the financial sector lobby and its allies in both parties.

With so much pressure to avoid a shutdown, opponents of the banks could not strip the reversal out; now the FDIC says major banks could be keeping as much as $10 trillion of these investments on their balance sheets, benefitting from the subsidy of assumed federal protection.

“Sticking these provisions in much bigger, more complex, must-pass legislation enables them to disguise and hide their support for Wall Street and prevent the American people from knowing what they are up to and holding them accountable,” Dennis Kelleher, CEO of the reform group Better Markets, wrote last year.

In other words, if Congress had been focused on what was actually in the bill, rather than Cruz’s strained attempts to use it to block the president’s immigration policy, the actual substance might have changed. Even members of his own party were mad at Cruz’s antics—”I don’t see how conservative ends are achieved,” Senator Jeff Flake told Politico. The only winners were the banks.

Cruz has already sparred with his competitors for the Republican ticket over financial regulation, saying he would not have approved bank bailouts in 2008, while other candidates say they would need to be realistic about protecting the US economy, as George W. Bush was. Expect some pointed rejoinders for Cruz at tonight’s Republican primary debate.