This startup wants to compose music for you with the help of AI

Think back to the last time you watched a vlogger-produced YouTube video, or listened to the opening chords of a podcast intro. Odds are, you heard a little riff of music—nothing recognizable, just a burst of sound a little bit like the commercial jingles you hear on FM radio airwaves.

Think back to the last time you watched a vlogger-produced YouTube video, or listened to the opening chords of a podcast intro. Odds are, you heard a little riff of music—nothing recognizable, just a burst of sound a little bit like the commercial jingles you hear on FM radio airwaves.

These snippets help video content creators brand their work by establishing a mood, but it’s rare for a video creator to actually compose the piece himself; the skillset needed to edit a short video differs wildly from the know-how required to string chords together. “Music is the one area of the video creation process that people don’t have a hand in themselves,” Ed Rex says. “So we thought we could give them a tool to create their own music really easily.”

Rex is a composer-turned-coder and CEO who runs a young company called Jukedeck. The startup sprang from a curious thought Rex had while studying music theory at Cambridge University. “If computers could be involved in the music making process,” he wondered, “what would that mean?” The question hints at a broader debate that continues to engage programmers and artists alike: Can machines exercise creativity?

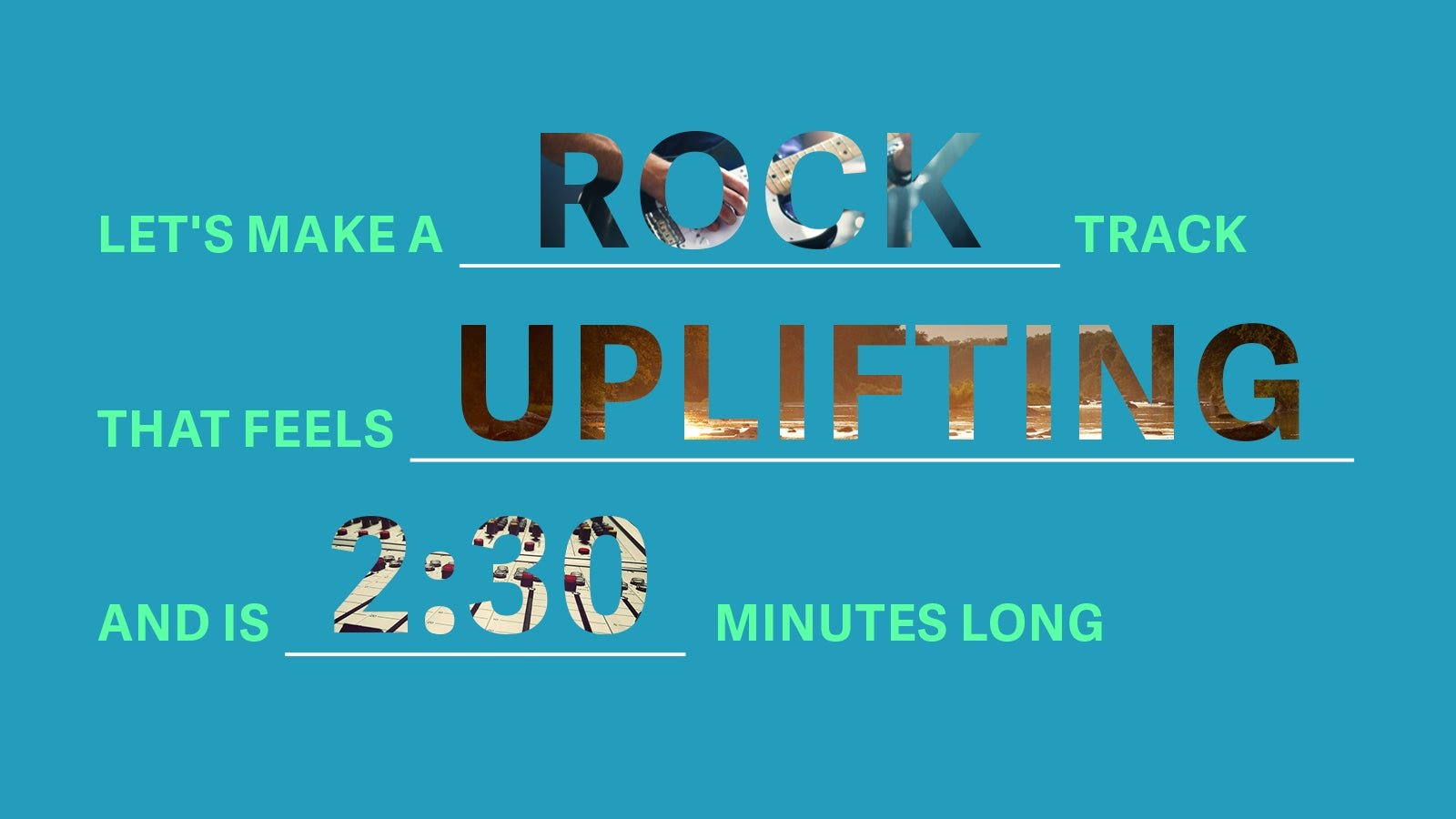

Jukedeck’s platform, which uses artificial intelligence to write music, seems to suggest that the answer to the question is yes. Rex and his cofounder Patrick Stobbs—who he’s known since they sang in the King’s College Choir at eight years old—built a system that uses machine learning algorithms to choose one note after another, generating a short and sonically pleasant piece of music. From a user’s standpoint, Jukedeck works by first offering you four categories of music—folk, rock, electronic, ambient—and then asking what kind of mood you need. Uplifting? Meditative? Angry? Tell it how long the piece should last, and Jukedeck takes about 20 seconds before delivering a custom-made MP3. Users can request as many as they’d like, and Rex says no two are alike.

Bespoke music designed by algorithms is the stuff of the future. Replacing human musicians is far from the point—Rex says, “it’s not as simple as codifying it and making music,” partly because “we as a society haven’t really agreed on what makes a good piece of music.” Instead, Jukedeck is harnessing data about music to empower video producers, who generally can’t make music or negotiate through copyrights on existing music.

Rex plans to keep Jukedeck competitive by expanding its catalog (if you can call it that, given that everything gets generated on the spot) by adding more available genres. “We’ve had requests for funk and hip hop and lounge music.” After an invite-only trial, Jukedeck launched to the general public in December at Techcrunch Disrupt London, and it already has had over 100,000 tracks created, many by vloggers, Rex says.

As much as that pool of users gets to benefit from the site’s data-driven approach to music creation, Jukedeck can grow by using the data its users create. In other words: every time a user chooses an MP3, Jukedeck learns a little bit more about what musical qualities are most desirable. With that, Jukedeck can cater to its niche base of users, and perhaps also contribute a bit of knowledge to the study of musical theory—ultimately generating and sharing data that’s good for machines, artists, and music enthusiasts everywhere.

***

Some may recall the old adage: “early is on time, on time is late.” This sentiment holds particular relevance in today’s rapidly evolving tech landscape: Being up to date is not good enough. Companies need to proactively anticipate what the future holds and adjust accordingly—that’s the idea behind Dell’s “Future Ready” initiative, aimed at helping customers stay ahead with cutting edge tech solutions and services. This piece is one of a four part series in which Dell and Intel highlight companies that embody the “Future Ready” mentality, striving to foster and embrace innovations in mobility, security, scale, competitive strategy, and sustainability.

Is your business Future Ready?

This article was produced on behalf of Dell and Intel by the Quartz marketing team and not by the Quartz editorial staff.