It’s time to stop segregating Oscar nominees by gender

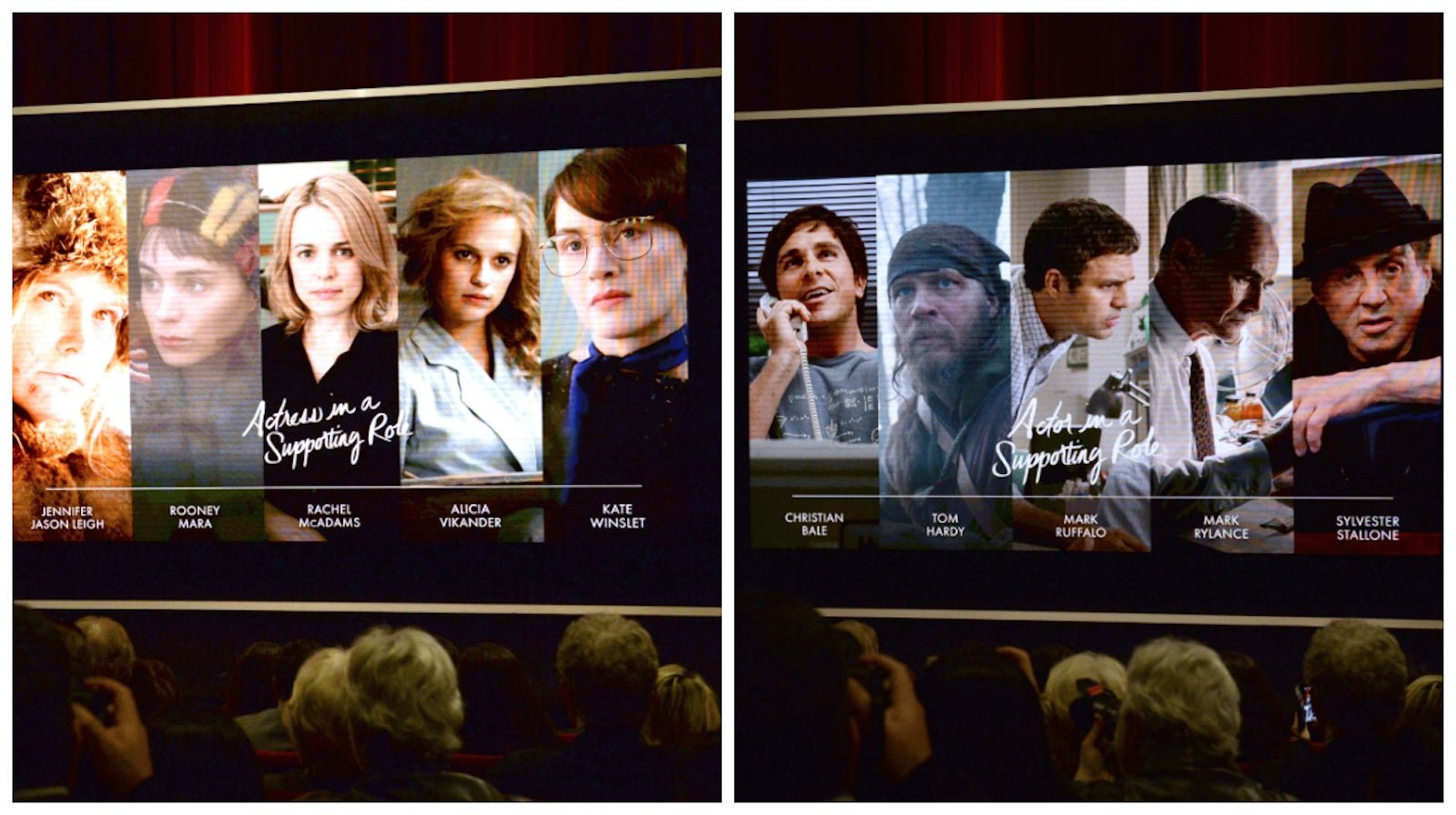

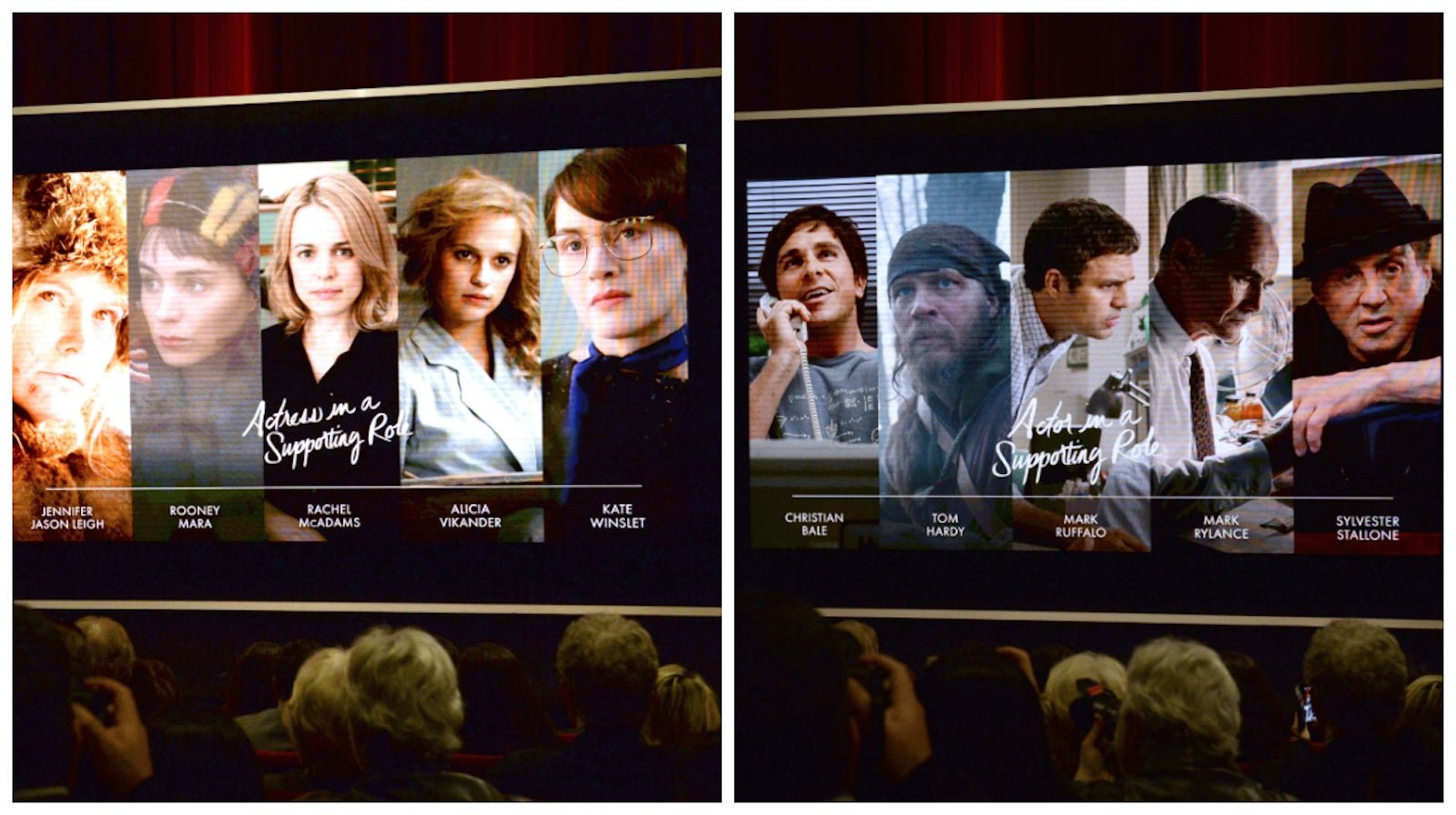

On January 14, 2016, the nominees for the 88th Academy Awards were announced at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills—and, almost across the board, those nominees were largely white and male. Again.

On January 14, 2016, the nominees for the 88th Academy Awards were announced at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills—and, almost across the board, those nominees were largely white and male. Again.

At a time when the entertainment industry is producing so many great features that break away from the white, male point of view, it’s still somewhat shocking to see so many talented women and people of color passed over for their industry’s highest honors. On the other hand, in many ways this kind of slight is business as usual in the movie industry.

Outraged celebrities like Jada Pinkett Smith and Spike Lee are publicly boycotting the Oscars because of the nominees’ prevailing whiteness, and social media users have been mocking the ceremony’s monochromatic shine for weeks. But hashtags can only do so much. It’s time to move from acknowledging the issue to actually addressing it.

Amid the backlash, the Academy has unveiled changes to its member requirements in an effort to make Oscar voters more diverse. This is an important step, but it is far from comprehensive. How can we ensure recognition of a diverse array of talent within an industry that’s got an obvious and seemingly unshakeable bias towards white men?

A few years ago, Pacific Standard offered a novel solution to the lack of gender parity at the Oscars: What if every award, from Best Director on down, were segregated by gender? It’s hard to argue with the fact that gender segregation within acting awards has brought many more women to the table, raising their profiles and giving them more clout in Hollywood in the process. This year, 20% of female Oscar nominees were nominated in acting categories (compared to 6.4% of male nominees).

If Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and other awards were also split into two separate gender categories, the theory goes, the Academy would have no choice but to recognize women in Hollywood. The hope is that this recognition would help to budge the stubbornly low percentage of women working as screenwriters, directors, producers, and other essential roles in film.

In practice, however, history suggests that more awards for women moviemakers wouldn’t necessarily change the discrimination that keeps them a minority within the industry. A better solution might be a move in the opposite direction. Rather than further segregating the Academy Awards by gender, we should remove gender segregation entirely, evaluating actors on their talent alone, with no consideration for gender.

The notion that women and men have some inherently different attitude or approach towards acting is antiquated and should be abandoned. This is especially true as our evolving understanding of gender, and the increased prominence of trans and gender non-conforming people within Hollywood, makes it less sensible to segment nominees into pink and blue boxes.

Would removing gender segregation from the Academy Awards result in fewer nominations and awards for women? Perhaps. Literary and fine art prizes rarely segregate by gender, and it’s no secret that they tend to be dominated by white male nominees and winners. But in the same way that the blinding whiteness of the 2016 Oscars has brought attention to racial discrimination within Hollywood, an entirely male slate of acting nominees might force us to finally confront Hollywood’s bias against women.

Or maybe it would actually start leveling the playing field, with the added bonus of breaking down some of the archetypal roles that male and female actors so often seem slotted into. Imagine a Best Actor category including both Michael B. Jordan for Creed and Hillary Swank for Million Dollar Baby.

Acting Oscars have divided by gender since the first-ever Academy Awards, yet things remain grim for actresses in Hollywood—not quite as grim as their writing and directing counterparts, but grim nonetheless. A recent report from the Geena Davis Institute found that just 30% of film roles are written for women. In the world of movies, male characters outnumber female ones by a ratio of 2:1. Again, that’s significantly better than the gender breakdown among directors, where there are more than 14 men for every single woman. But if over 80 years of gender segregation in awards has yet to solve the issue of women’s underrepresentation in film, that doesn’t speak particularly well of the tactic’s success rate.

For all the weight that awards carry in the world of movies, they are just awards—not jobs, not equal pay, not respect. Giving more awards to women, or to people of color, will not fix a broken and biased system. If anything, guaranteeing diverse representation at the Academy Awards through awards divided by gender merely makes it easier to ignore the aggressive lack of parity within the inner workings of Hollywood. If women receive equal screen time at the awards show, it’s easier to turn a blind eye to other, more important, places they’re not receiving equal levels of representation, attention, and money.

We need to take a multi-pronged approach to this issue. Trying to force diversity into the Oscars by creating more gender-based categories may be a short-term solution, but it won’t do much to challenge outdated notions about who’s best suited to write or direct a blockbuster, or whether films that feature female or people of color as leads can do well in overseas markets. Doing away with gender categories could increase overall diversity in the long term, but those changes could take years to evolve. And ultimately, any updates to the Oscar system will face an uphill battle if the culture of Hollywood remains the same.

At the end of the day, studios big and small need to make the conscious decision to hire more women. This decision won’t guarantee that the Oscars will become more diverse, but it will make it much, much harder to ignore movies made by people other than white men. More importantly, it will ensure that women are consistently getting work within the film industry. That’s far more important than any Academy Award.