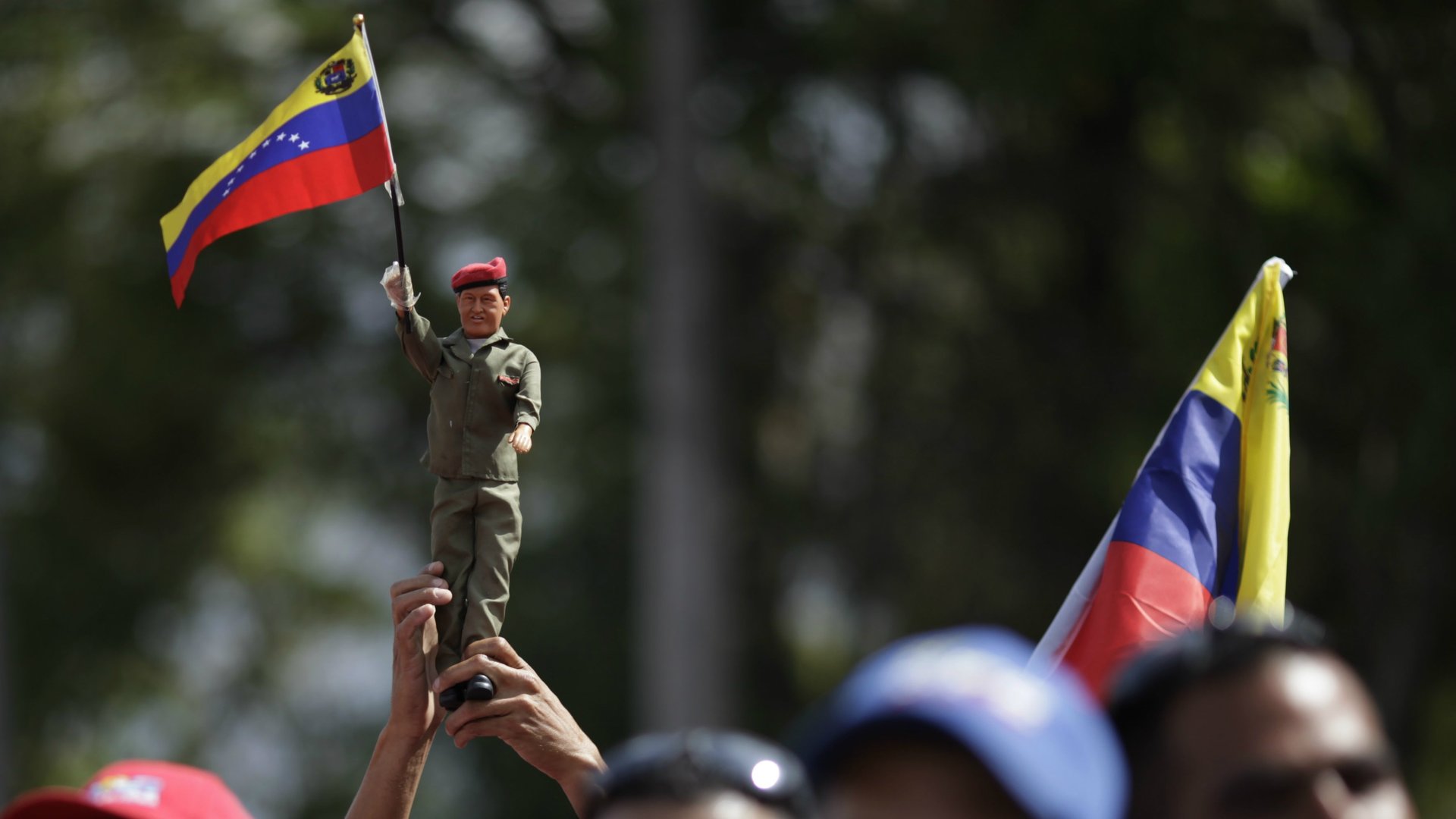

Today’s Hugo Chávez’s funeral but Venezuela won’t let go so easily

Hugo Chávez may be dead, but he is not going away.

Hugo Chávez may be dead, but he is not going away.

Like Eva Peron and “Che” Guevara, Chávez is poised to join the pantheon of heroes to the Latin American left, living on as a political force for years or even decades to come.

That’s hardly good news for wealthy elites in Venezuela, along with US media elites, pundits and the US government. They are hoping that with Chávez’ funeral in Caracas today, his Chavismo movement that led the poor to rise up and take power for the first time in Venezuelan history will become a thing of the past.

The oligarch-owned Venezuelan newspaper El Universal headlined the day after El Comandante’s death that “The Chávez-less era begins,” as if 14 years of Chávez’s rule could be magically wiped off the slate and a new Venezuela—really the same old pre-Chávez Venezuela—be created.

But the “Chavistas” are not going anywhere. Venezuela changed forever when Chávez won the presidency in 1998. The poor majority will no longer accept an oil-rich country where a tiny ruling class lives in gated mansions and everyone else struggles to eat.

In an extraordinary spectacle on Wednesday, Chávez’s body and coffin were carried through the streets of Caracas for miles as hundreds of thousands of red-shirted admirers marched behind him for hours in the scorching sun. His funeral on Friday promises to be one of the most memorable events in modern Latin American history.

Anointed successor, Vice President Nicholas Maduro, seems poised to easily win the new election for president, which may take place within a month. His likely opponent, Henrique Capriles, is a state governor and an oligarch. He spent the weekend before Chávez’s death visiting relatives on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The New York Times reported that Capriles’s sister has a $4.1 million apartment there.

In contrast, Maduro hails from the sprawling slum of Catia in Caracas. He was at Chávez’s side from the time the former paratrooper first emerged on the public stage by leading a coup in 1992 against a hated government.

Chávez, who himself was born in a mud hut in rural Venezuela, was the poor people’s president—the first in Venezuela’s history. He was a beacon to millions around the world, though hated by many others.

He was demonized by the elites in life, and now—says the left-leaning media watchdog group FAIR, which stands for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting—he is being demonized in death as they try to write and rewrite his legacy—to bury him once and for all. (True to form, even in death, Chávez won’t go away. He’s going to be embalmed and permanently on display in a glass casket.)

Of course, Maduro is no Chávez—no one in Venezuela is. Chávez was a once-in-a-century figure, a gifted orator who had a quasi-religious connection with the poor majority who viewed him more as a messiah than a politician. It’s possible that with him gone, his movement will collapse.

But it’s much more likely his followers will never forget the man who turned Venezuela upside down.