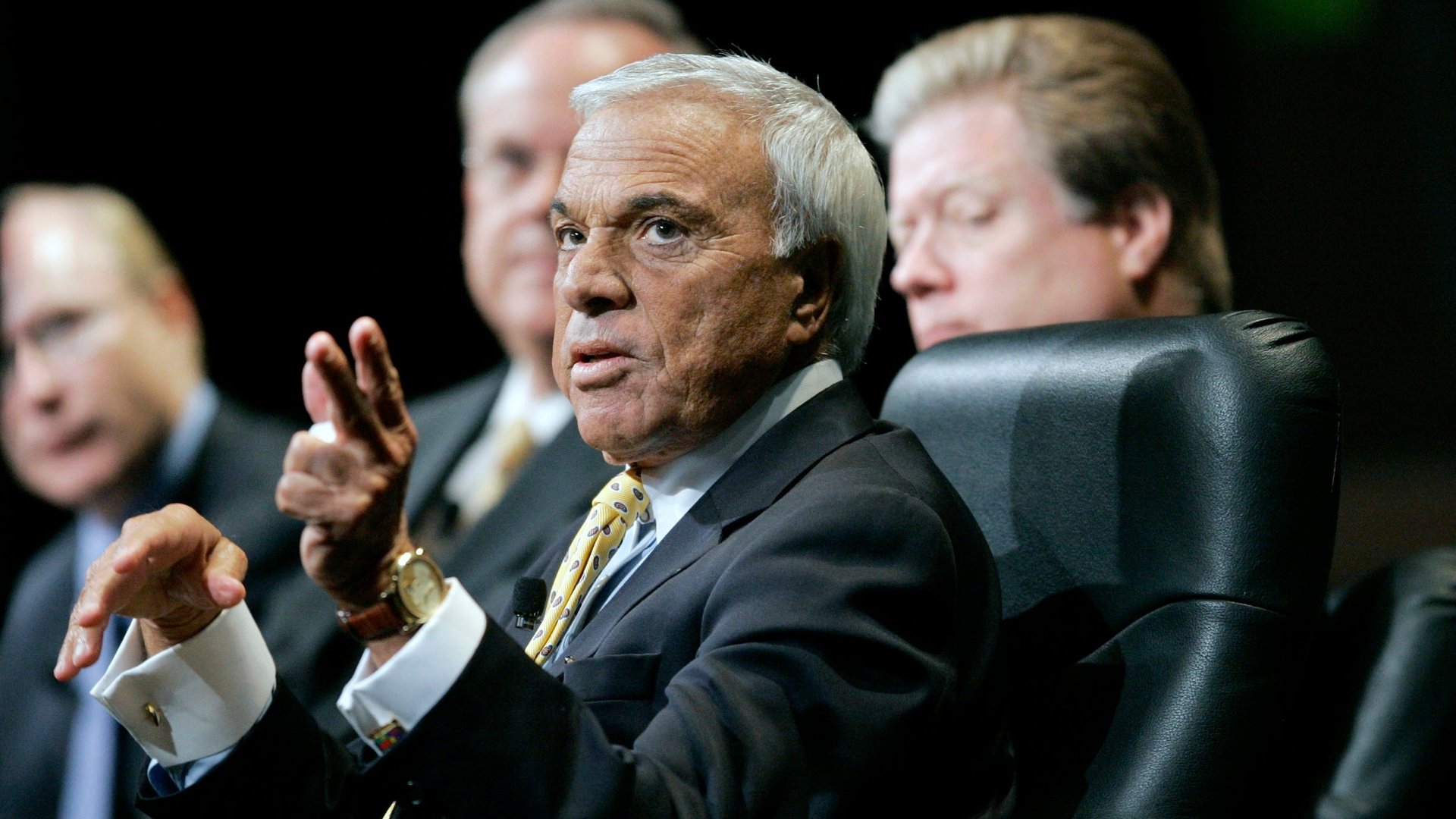

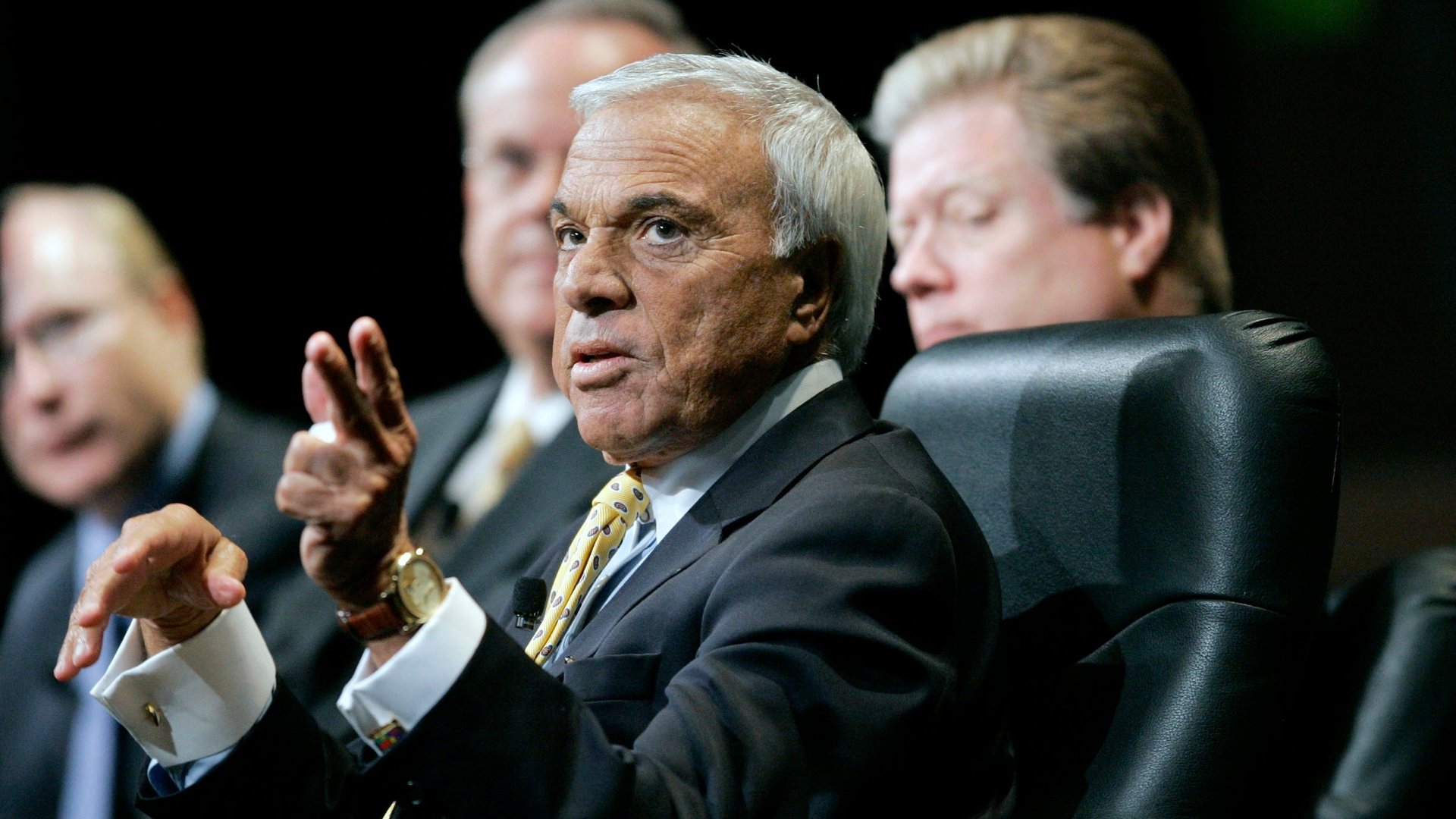

Former Countrywide shareholders hope for another chance to bring Mozilo to justice

With the statute of limitations on civil cases in the US usually limited to five years, many of the root causes of the US financial crisis are now falling beyond the civil courts’ reach. So a lawsuit before the Delaware Supreme Court could be one of the last chances for investors to hold people accountable for their losses: in this case, former Countrywide CEO Angelo Mozilo, who headed a company that was at the nexus of the subprime mortgage disaster.

With the statute of limitations on civil cases in the US usually limited to five years, many of the root causes of the US financial crisis are now falling beyond the civil courts’ reach. So a lawsuit before the Delaware Supreme Court could be one of the last chances for investors to hold people accountable for their losses: in this case, former Countrywide CEO Angelo Mozilo, who headed a company that was at the nexus of the subprime mortgage disaster.

Countrywide, one of the biggest mortgage lenders in the US, was on the verge of bankruptcy because of bad loans it made, until it was sold to Bank of America in 2008. Its actions contributed to the financial crisis that caused a record number of home foreclosures, the collapse of several banks and thousands of job losses. The shareholders are alleging that fraudulent actions by Countrywide pushed it into the merger with BofA at a fire-sale price, making the merger itself fraudulent.

Many of the lawsuits to bring Mozilo and other Countrywide directors to court were dismissed or settled. In October 2010, Mozilo settled with the SEC regarding securities fraud and insider trading allegations and agreed to pay $67.5 million. As a result, he was able to avoid a trial.

To win their case in Delaware, the former Countrywide shareholders must first prove they are allowed to sue. Hearings will likely occur later this spring. Former investors who no longer own stock because of a merger usually lose their standing to bring a lawsuit, but Delaware allows for a “fraud exception,” and the two sides are arguing over what qualifies under that rule.

The shareholders argue that Countrywide misled the public on numerous issues, including on the quality of its loans and the company’s financial situation. They say all of those actions were part of the larger fraud of the merger, since those decisions necessitated the sale to Bank of America.

The Countrywide side argues that shareholders are wrongly trying to expand the law by including alleged actions by Countrywide directors in the lead up to the merger, when the law requires proving solely that the merger itself was a fraud.

If the shareholders win, it could have broader implications for ailing companies that may have engaged in questionable behavior before selling themselves. In a 2010 opinion on Countrywide, the Delaware Supreme Court seemed to open the door to allow the shareholders’ argument. The court said that the investors claims “suggest a potential relationship between the directors’ alleged premerger fraudulent conduct and the rapidly and severely depressed stock price on which the merger consideration was based.”

Regardless of what happens in the Countrywide case, history will likely show that very few executives were held liable for the financial crisis and many, despite settlements they paid, are still living the high life. For Mozilo, the SEC fine represented only a fraction of his $600 million net worth.