These architects are in the process of reshaping New York City’s skyline

New York has long been a laboratory for architecture—a “theater of progress,” as Rem Koolhaas called it in his seminal 1978 text, Delirious New York. Yet even within that tradition, 2016 is poised to be a defining year for New York’s future development. Already dubbed “the Manhattan skyline’s biggest year ever,” 2016 and the brewing changes it holds will impact, most importantly, city life, as the architects shaping New York push the boundaries of what the modern city can be.

New York has long been a laboratory for architecture—a “theater of progress,” as Rem Koolhaas called it in his seminal 1978 text, Delirious New York. Yet even within that tradition, 2016 is poised to be a defining year for New York’s future development. Already dubbed “the Manhattan skyline’s biggest year ever,” 2016 and the brewing changes it holds will impact, most importantly, city life, as the architects shaping New York push the boundaries of what the modern city can be.

Some of these changes are already transforming New York city’s neighborhoods. The most prominent example of this, and one of the most significant projects of recent years, is Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line. Not only did it pave the way for a new, holistic approach to urbanism focused on reviving existing, untapped space through designs that address contemporary needs, the High Line’s success has also led it to become a locus for new development. With a kind of gravitational pull, the High Line has propelled a residential boom from the Meatpacking District through Chelsea that will see dozens of very exciting projects. The most recent addition is SHoP’s proposal for a 10-story timber-framed structure. This would be the tallest of its kind in the city and a departure from the traditional steel and concrete palette of high-rise construction.

Nearby, the recent opening of Renzo Piano’s new building for the Whitney Museum of American Art in May 2015 was the first in a wave of projects that will reshape New York’s cultural sphere. Some of the city’s leading institutions—the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and The Frick Collection—have all recently announced plans to expand and revitalize their current residences. Early glimpses at some of these projects show that architects are focused on defining a vital new role for museums in the city by expanding their accessibility and creating gallery spaces tailored to the experience of the works on view.

The biggest changes to the skyline, in the traditional, vertical sense, are concentrated in a small area near 57th Street, where four of the world’s tallest towers will rise between West 53rd and West 59th, slated for completion by 2019. This massive growth can be attributed to the area’s coveted proximity to Central Park, the evolving nature of the real-estate market (all of the towers will be residential), and its location within a district with unique sanctions to build skyward. The maximum allowable floor area ratio (FAR) is high in this area and, when air rights are factored in (there is a swarm of low-lying landmarks here, so there’s ample vertical square footage up for grabs), the sky really does become the limit. For Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park Avenue, for example, upwards of 115,000 buildable square feet were added to the structure from the transfer of air rights.

In addition, a rezoning proposal for the East Midtown area—from East 39th Street to East 57th Street, between 3rd and 5th Avenues—has been in the works for quite some time (it was originally attempted by former mayor Michael Bloomberg) and could lead to an increase of super-tall developments in the area. This new crop of slender “pencil towers” is made possible in part by progress in building techniques but also due to a clearly defined function. Residential buildings require fewer elevators than office towers, allowing them to take up less area. It would also be amiss not to factor in the influence of their future residents, who aspire to own the best possible views, which is facilitated by many apartment units that occupy entire floors and offer 360-degree access to the city.

On the sustainability front, we haven’t heard too many offices touting their LEED Platinum certification lately—but that’s only because this has become the standard in recent years. With the urgency of climate change, architects now have to ask bigger questions, which has led to more active forms of addressing the environment. Take Bjarke Ingels Group’s proposal for the Dryline, for example. The protective barrier was designed to encompass the western waterfront of Manhattan, from West 54th Street all the way down and around the island through Battery City and back up to East 40th Street. The 10-mile area would see the creation of a green, urban oasis for leisure and sporting activities, equipped with flooding defenses to protect the city in the event of another Sandy. The optimistic project would be introduced gradually: in the short term it would provide a new, much-needed green space for residents while in the long term it would set up a new system to protect the city from its low-lying vulnerabilities.

For architects today, the challenge is largely centered around how to evolve with the current times. During a panel discussion at the 92nd Street Y this month titled “The Future of New York’s Skyline,” Rick Cook, a founder of COOKFOX Architects, summed this up in just one word: resilience. As architects continue to ask themselves “How will we meet the sky?” “How will we meet the water?” and “How will we connect to nature?” they will answer with new forms of cohabitation within the city.

Tadao Ando—

Based in Osaka

Tadao Ando’s discreet statement at 152 Elizabeth Street in Nolita is re-envisioning the state of architecture in the city in a different manner than the soaring towers and ambitious formal innovations of his contemporaries. For his first building in New York, the Pritzker-prize winner transposes his signature use of concrete to the corner lot. Described as a “crystalline box,” the poured concrete and metal structure is elegantly cloaked by sheets of glass. The chosen glass features airport-quality soundproofing, so despite the building’s overall transparency, from the inside residents will feel like they are cocooned in a space that is at once visually engaged with the surrounding city and safeguarded from its incessant noise.

Throughout the boutique building—which will contain only seven residences—Ando (who also worked alongside Gabellini Sheppard Associates on the interior design) was focused on incorporating the elements—light, sound, air, and water—and using each as a distinct material in his architectural vision. The site will include one of the largest living green walls in New York City, a floor-to-ceiling water wall in the entrance vestibule and, most curiously, a volumetric fog and light installation carved into one of the exterior walls that will change at different times of the day, according to weather conditions. Altogether, Ando’s New York debut retains his signature approach of creating cohesion between architecture and its natural surroundings—and endeavors to embed a small sanctuary to nature into an unsuspecting corner of the city.

Annabelle Selldorf—

Based in New York

Understated elegance is the hallmark of Annabelle Selldorf’s diverse portfolio, which includes apartment renovations for New York’s elite, the transformation of former roller rink and nightclub The Roxy into Hauser & Wirth’s 18th Street gallery, and the careful restoration of the Neue Galerie on the Upper East Side. She brings a sensitivity for materials to her projects, always responding to the palette of her context with one eye toward tradition and the other toward contemporary expression. At 10 Bond Street, for example, she clad the façade in terracotta—a material traditionally reserved for ornamentation. The curved panels were glazed in a deep copper hue, echoing the building’s primarily brick surroundings.

Within her oeuvre, the Sims Sunset Park Materials Recovery Facility in Brooklyn seems a bit out of left field, but Selldorf deftly converted the industrial site with her minimalist touch. With recycled materials used throughout, the building embodies its program. The site fill is made out of recycled glass, asphalt, and rock reclaimed from the Second Avenue subway construction; the structure is made from recycled steel and the plazas are finished with recycled glass. The facility will also contain one of the largest applications of photovoltaic panels in the city and a 160-foot-tall wind turbine that supplies up to 10% of the facility’s power. But the building doesn’t only consider the impact of recycling in a physical way; one of the project’s defining features is the inclusion of an education center that contains classrooms, exhibition space, and a viewing platform onto the processing facility where visitors can see the recycling process in action.

Bjarke Ingels—

Based in Copenhagen and New York

Bjarke Ingels moved to New York from Copenhagen in 2010 to oversee construction of Via at West 57th Street, and has since developed numerous stateside commissions. Via at West 57th Street is near completion on its Hudson River-facing site and is the project that most clearly draws on Ingels’s Danish roots. Its sloped pyramid form is a hybrid of the European perimeter block with an interior courtyard and the typical Manhattan high-rise. The skewed slope of the building ensures that western sun reaches inside the courtyard—a communal garden that Ingels has likened to a “bonsai Central Park”—and secures the opportunity for each apartment to have views of the river and outdoor space.

Ingels sees his practice as hitting the sweet spot between utopian ideas and pragmatic realities. As he once explained, each project is a specific response to a complex network of factors:

Some people use only the color white, or only 90 degrees. What defines their style is the sum of all their inhibitions. And I think we try to put ourselves in a position where we can be free to choose any weapon of choice in each and every case to match the context, the culture [and] the climate in the best possible way.

When he received the commission for 2 World Trade Center, the last skyscraper to be built at the revered site, he had to mitigate some of the most delicate dynamics involved in building in New York City. He views the adjacent 9/11 Memorial as a sacred place for remembering and considers 2 WTC a symbol of the city manifesting its defiance in the face of terror. As such, he conceived of the building as having two distinct faces: the smooth, tall, and slender side, which faces the Memorial with solemn respect, while the stepped green terraces of the northern side greet TriBeCa with vibrancy. At the 92nd Street Y last week, he recalled meeting a man whose brother was a first responder during 9/11 and tragically lost his life that day. He interpreted the tower itself as a unique memorial, a clear symbol within New York’s skyline—a stairway to heaven.

SHoP Architects—

Based in New York

Since their high-profile work on Barclays Center, SHoP Architects have become one of the definitive voices shaping New York—and not just Manhattan. With major commissions in the works in four of the five boroughs—including the Domino Sugar Factory redevelopment, a plan for Atlantic Yards, a mixed-use tower in Hudson Yards, and a residential complex in Hunter’s Point, among others—the studio seems almost impossibly busy.

Though most of their slated projects are still on the drafting board, you might be familiar with the sight of two towers rising along the East River at 626 1st Avenue, characterized by a slight lean around mid-height, as though they were being pinched together. Once completed, the structures will stand out because of the distinctive gleam of their façade. The north and south faces are clad in copper panels with a gradient of apertures, while the east and west faces feature a glass curtain. The two towers will bring a total of 800 new apartments to the downtown area, along with a plethora of amenities like the enviable pool that will be suspended over the city in the towers’ connecting bridge.

In Midtown, the studio is working on what will become one of the tallest towers in the city and the skinniest skyscraper in the world. 111 West 57th Street rises straight up in the north while its southern façade employs a series of very subtle setbacks, reducing the shade that the tower will cast. The exterior makes a nod to the golden era of Manhattan skyscrapers in the 1920s, with a dark glass curtain wall covered with terracotta and bronze trimming.

David Adjaye—

Based in London and New York

London-based architect David Adjaye was unanimously selected by the Studio Museum in Harlem’s board to design a new home for its collection at the 125th Street location. This comes as no surprise, as the project is a natural extension of Adjaye’s portfolio, which includes a wide range of works in the cultural sector. Most notable is Adjaye’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is currently under construction in Washington DC, where it will fill one of the last remaining voids along the National Mall. This project in particular has come to exemplify Adjaye’s core ethos, as he has explained:

My practice absolutely believes that architecture is the physical act of social change, and the manifestation of it. I believe in architecture as a social force that actually makes good. And one that edifies communities.

The Studio Museum was originally founded in 1968 in a small loft space and moved in 1979 to a former New York Bank for Savings building that was renovated and extended to form its current site. Adjaye’s project will be the first structure designed specifically for the Studio Museum and its focus is on increasing interior spaces while retaining a dynamism that reflects and resonates with its vital neighborhood, Harlem. As such, the design draws on Harlem’s existing architecture, its traditional brownstones, churches, and vibrant sidewalk life. The expansion will double gallery space (which will allow the museum to significantly extend its schedule of exhibitions), grow its artist-in-residence program, and increase public programming areas by 60%. Ultimately, the project will deepen the Studio Museum’s role as an inviting, central meeting place for the community at large. The design features a transparent ground level with an “inverted stoop,” a set of steps that begin at the sidewalk, descend, and can be used as a stage for lectures, screenings, and performances (some of these spaces will be open free of charge to increase accessibility).

Diller Scofidio + Renfro—

Based in New York

The High Line is a prominent example of Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s interest in carving out intimate, alternative public spaces in the city. Though it runs nearly 1.5 miles long, the linear park actually covers a tiny footprint—walking along it can often feel more like waiting in line—yet manages to inject the site with a unique assemblage of gathering places. Similar ideas are explored in the nearly complete Medical and Graduate Education Building for Columbia University Medical Center. Its major design gesture is the “Study Cascade,” a 14-story grand staircase with oversized landings from which an intricate network of social and study spaces offshoot. Similar to the endlessly varied meander that the High Line provides, the “Study Cascade” offers an unexpected group of interconnected spaces that are conducive to both collaborative teaching and solitary work.

Meanwhile, the firm’s fantastical proposal for the Culture Shed at Hudson Yards pulls out another thread that runs through the studio’s interdisciplinary portfolio. The design, a collaboration with Rockwell Group, establishes a highly flexible cultural center adaptable to the visual arts, performing arts, and creative industries. It proposes a column-free exhibition space covered by a 140-foot retractable “shed” that can be deployed using industrial crane technologies to expand or contract the space for changing needs. Or, the structure can be opened fully to create a large and freely accessible open-air plaza.

This brings to mind DS+R’s Blur Building—a pavilion for the 2002 Swiss Expo that was sited 400 feet out into Lake Neuchatel and consisted of a simple metal framework that was periodically activated by a fog-mist system, enveloping visitors in what essentially amounted to be a man-made cloud—as well as their unrealized proposal for the Bubble—a pneumatic structure that would serve as an expansion to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC to create pockets of space for public programs, as needed. What unites these projects is a sense of architecture as ephemeral atmosphere, a view that is centered on building for the fluidity of events and creating spaces that can adapt to the complexity of urban life. (This spirit is also present in their new project for the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, which opens to the public on January 31st.)

Zaha Hadid—

Based in London

Among the many architects now leaving their mark in the area, it is the arrival of architecture doyenne Zaha Hadid that will undoubtedly set the bar high for the High Line’s future development. Slated for completion in early 2017, the 11-story steel and glass 520 West 28th will gently hug the linear park and continues Hadid’s career-long exploration of fluid, dynamic forms. Hadid cites Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim as inspiration for the sculptural work, which seeks to establish a series of dynamic continuities: between the city and the High Line, between the public realm and the private residences.

The structure follows a clever and elegant design whereby its 11 stories give way to 21 floors staggered along a central chevron device. While the building’s sleek volumes are not quite as futuristic as those we’ve come to expect from Hadid, its sculptural facade—handcrafted out of metal—embodies the industrial spirit of its surrounding neighborhood. As the exterior looks to the history of its setting, the interior defines a sense of modern luxury, with unparalleled amenities like a private IMAX theater, a robot-operated garage, and a fully-equipped spa suite. The curvilinear logic of the structure is followed into each of the 39 residential units, which echo the motif in furnishings designed by Hadid herself, like a swooping kitchen island and textured bathroom walls.

RAAD Studio—

Based in New York

While most architects working in New York strive to eschew the density by building higher and higher, James Ramsey of RAAD design studio has found untapped potential in the city’s real estate by going in an unlikely direction—underground. Together with co-founder Dan Barasch, Ramsey has spearheaded The Lowline, an alternative public space housed in a linear, one-acre site on the Lower East Side in the defunct Williamsburg Bridge Trolley Terminal (it’s been out of service since 1948). The Lowline’s proposed solar technology system will draw light down into the cavernous space and revive the historic site—which has retained its original architectural features despite being abandoned for several decades—as the world’s first underground park. To do so, Ramsey developed “remote skylights”—a series of solar collection dishes above ground that gather, concentrate, and funnel light underground. Once the light has been captured and transmitted, a series of domelike fixtures underground use lenses and reflectors to distribute the light throughout The Lowline. This would allow enough light in for photosynthesis to take place and an abundant landscape to thrive.

Through the way it harnesses technology to radically transform an unconsidered urban space, the project has emerged as a kind of magical, slightly sci-fi twist to its predecessor, the High Line. After a successful Kickstarter campaign to raise initial funds in 2012, the Lowline Lab has been open to the public since October 2015 as a working prototype just a couple of blocks from the intended site. Over the past few months, the Lab’s experiments have seen over 3,000 plant types emerge—and even a miniature tree frog—proving that the Lowline is more than just a wild idea.

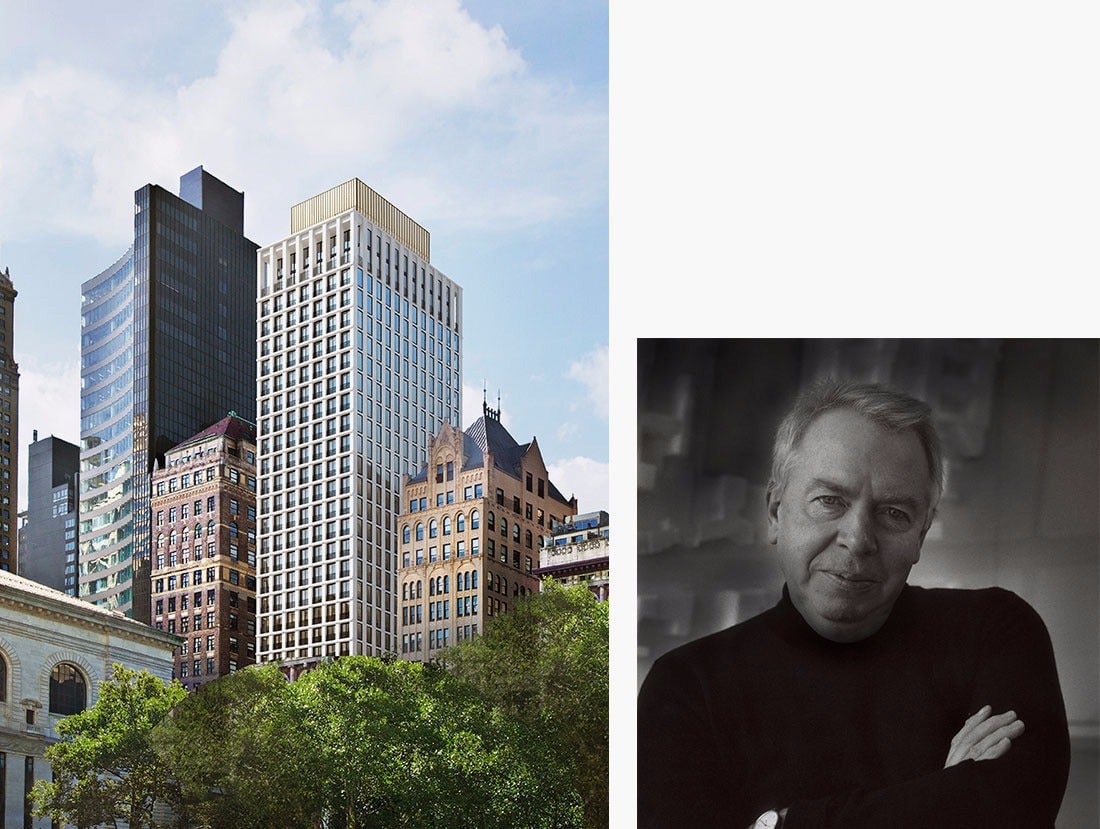

David Chipperfield—

Based in London

In contrast to the many synthetic, glass-clad buildings in Midtown’s predominantly business-oriented neighborhood, David Chipperfield’s The Bryant (16 West 40th Street) will overlook Bryant Park with a distinct, solid appearance. The concrete building—likely inspired by the monolithic, brick Bryant Park Hotel, originally designed by Raymond Hood and restored by Chipperfield in 2001—exemplifies an approach to architecture focused on its core elements: solid and void, mass and space, light and shadow. Each unit will benefit from a continuous band of floor-to-ceiling windows, framed by smooth terrazzo pillars (a seamless transition from the building’s facade) and custom millwork designed by Chipperfield to conceal all storage and appliances.

Jean Nouvel—

Based in Paris

Jean Nouvel’s “MoMA Tower” at 53 West 53rd Street has been underway for quite some time. The first drawings were submitted to the city in 2006, but the so called “Death Spire,” soaring at 1,250 feet, was considered too tall—and too expensive. After several revisions, the structure was reduced to a (mere) 1,050 feet before being approved, and the foundation was finally laid in December 2015, after nearly a decade of planning.

The structure is distinguished by its tapered form, composed of three separate volumes that peak at different heights and are burnished in different tones: silver, black, and gold. The exposed steel structural system, known as a “diagrid,” marks the exterior with its signature zigzagging pattern—but even though fragments of it peek through to the inside like bits of a sculpture, it also comes with some significant design inconveniences. The windows, for example, are inoperable and require a special ventilation system as well as custom shades.

As part of the larger redesign of the MoMA campus—which saw the much-contested demolition of the American Folk Art Museum—the tower will have the rare distinction of being integrated into Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s new MoMA expansion. The otherwise residential building will contain three new gallery levels on floors two, four, and five, which will be connected to and accessible from the museum’s other exhibition spaces.

Jeanne Gang—

Based in Chicago

It’s fitting that Jeanne Gang moved from her hometown in rural Illinois to Chicago to found her practice, Studio Gang, in 1997. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the city embodied the power of architectural imagination—despite its swamp-like terrain, it was here that the first building to be considered a skyscraper was erected in 1885. Gang has remained firmly rooted in this spirit of structural and material innovation, even as her growing studio has expanded out of the Midwest. Working across architectural and urban scales, Gang is focused on developing synergies between the manmade environment and nature.

A reverence for nature manifests throughout her built work, both visually and strategically. (She keeps birds’ nests on her windowsill as a reminder of organic beauty and resourcefulness.) Throughout Gang’s design for the American Museum of Natural History’s new Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, dramatic arched forms reminiscent of geologic formations weave through the museum’s space, carving out niches that will be used for special installations and forming fluid connections between galleries, classrooms, and other facilities. Allowing for surprising vistas to develop between the museum’s spaces, Gang’s intervention is a keen reflection of nature’s ability to induce wonder and exploration—and as such, becomes a metaphor for the AMNH’s overarching mission. Once the proposal gets all necessary approvals from the city, it will be slated for completion in 2019, to coincide with the institution’s 150th anniversary.

For the Solar Carve, which will take up residence on the High Line, Gang realizes lessons from nature more indirectly. The 12-story office tower has asymmetric profiles that almost seem like they have been shaved down or carved out of the structure. This is the result of studies of the sun’s path, which dictated the building’s form in order to minimize obstructing shadows while maximizing the flow of air and views of the Hudson. The resulting “gem-like” structure serves as a model for the benefits of solar-driven design and the ways in which sustainability can drive innovative architectural ideas.

Herzog & de Meuron—

Based in Basel

Referred to by many as the “Jenga” tower, the nearly complete structure at 56 Leonard Street presents a radical redefinition of the tower. In their design, the architects took a stance against the typical city tower—commonly defined by a simple vertical form with repetitive floor plans—by designing a sculptural figure composed of irregularly stacked, cantilevered volumes. The exterior shape is informed by a pixelated logic, with a variable staggering of the units, which becomes more dramatic toward the top. This free form generates 145 distinct apartments, which the architects describe as “houses stacked in the sky.”

The building is nuanced and singular, and like Herzog & de Meuron’s diverse portfolio, is guided by the principle of using “well-known forms and materials in a new way so that they become alive again.” In several of their past commissions, the interaction of art and architecture has taken on an important role, as in the silkscreened facade of the HdM Ricola Europe Building, or their collaboration with Ai Weiwei on the Beijing Bird’s Nest Stadium. The Tribeca tower upholds this tradition through a commissioned sculpture by Anish Kapoor—his first permanent public work in New York City—anchoring the tower to the street.

Rafael Viñoly—

Based in New York

It’s impossible to miss Rafael Viñoly’s super-skinny, super-tall 432 Park Avenue, the most prominent addition to the city’s skyline since Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s One World Trade Center. Looming over Midtown (it’s about 150 feet taller than the Empire State Building), the structure has generated a fair amount of criticism of its stark, minimal aesthetic, but there is something to be said for its bold simplicity. “I thought that a building that could be as tall as this one needed to have a well-balanced relationship between form and the actual structure of the building,” Viñoly has said. He cites Manhattan’s street grid, the sculptures of Sol Lewitt, and even a 1905 trash can designed by Austrian architect Josef Hoffman as sources of inspiration for the facade. The primarily residential tower has an exposed concrete structural frame, which allows for column-free interiors. At regular intervals throughout its vertiginous 1,396-foot rise, there are open spaces that house the building cores, a necessity for deflecting wind pressure and ensuring the tower’s stability despite its lean physique.

Viñoly is also working on a quieter expansion project for Rockefeller University, which will add two acres to the existing campus by building over the FDR East River Drive to create new laboratories, administrative space, a conference facility, a dining commons, and an outdoor amphitheater. The organic, sprawling nature of this project, which will also see upgrades to the adjoining section of the East River Esplanade, contrasts sharply with the monolith at 432 Park, but this variation follows Viñoly’s focus on each project as a site-specific study. “To me the critical thing in every building is the possibility of changing convention,” he has explained. “We effectively look at every project differently, we don’t believe that you have to be specialized.”

This post originally appeared at Artsy.