California’s gas leak is finally capped, but the next disaster could be right around the corner

Engineers have finally staunched a leaking gas well in southern California’s Aliso Canyon. Since the leak was discovered four months ago, the well has bled 96,000 metric tons of methane, the equivalent of running an extra 505,000 cars on the road for a year.

Engineers have finally staunched a leaking gas well in southern California’s Aliso Canyon. Since the leak was discovered four months ago, the well has bled 96,000 metric tons of methane, the equivalent of running an extra 505,000 cars on the road for a year.

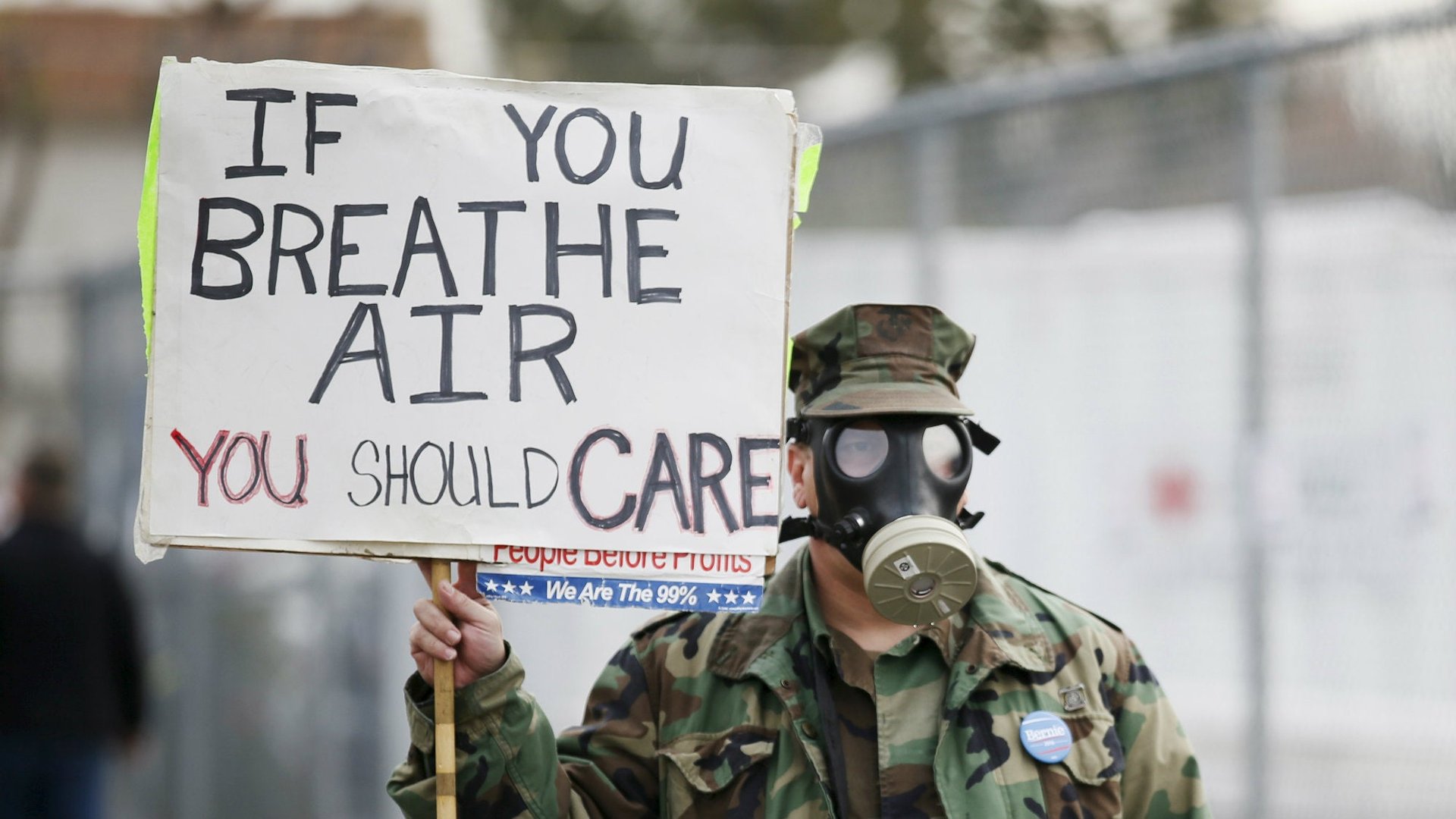

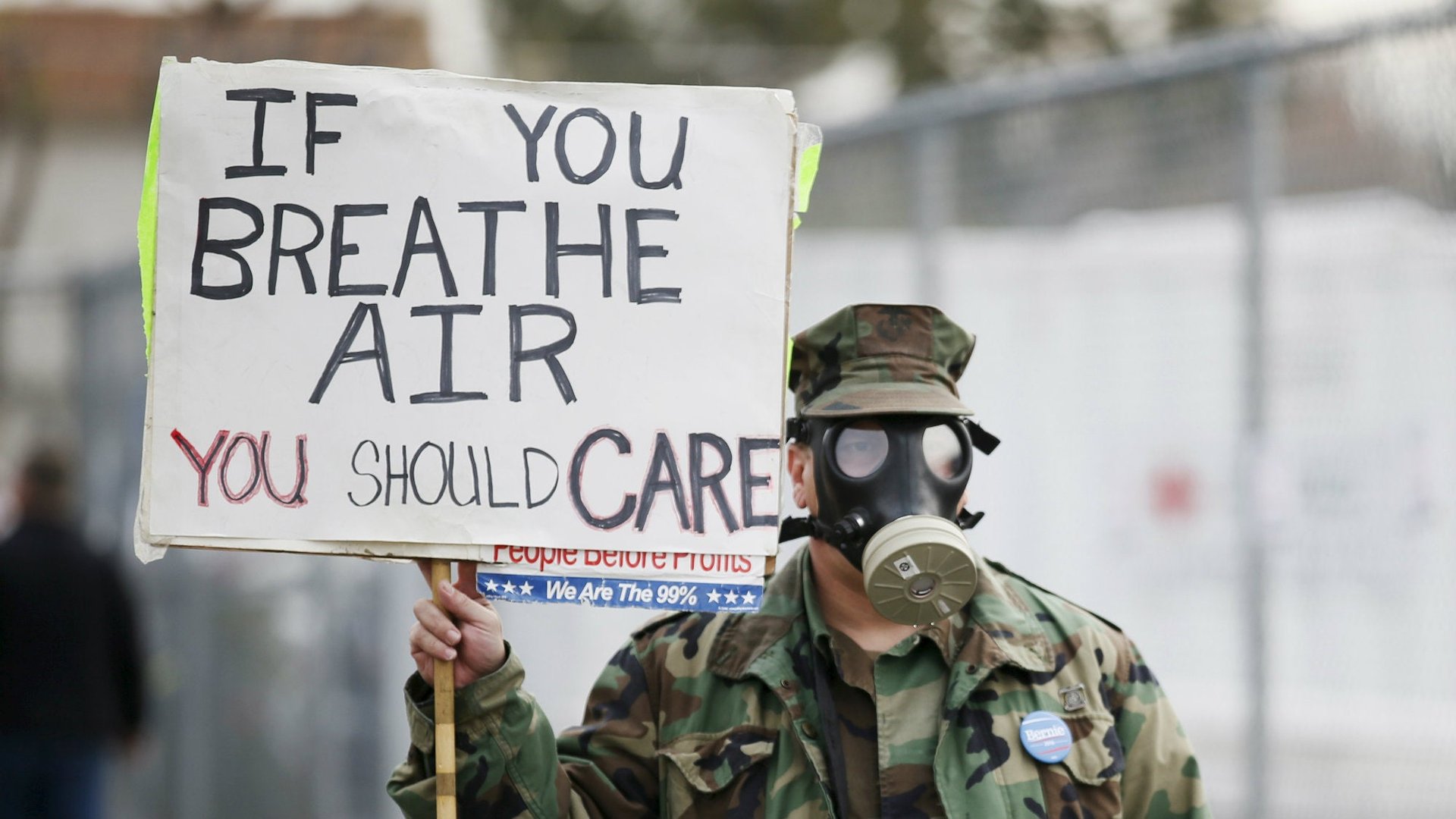

For neighbors, it’s been a nightmare. Residents started complaining of bad smells, headaches, and nausea in October. Under a court order, the well’s owner, Southern California Gas Co., has temporarily relocated more than 11,300 people. They’ll have seven days to move back home once regulators confirm that the well is permanently sealed.

The disaster in Porter Ranch, like the lead contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, is the result of aging infrastructure. In California, it’s a corroded storage well; in Flint’s case, rusting water supply pipes are to blame. The question isn’t if another Flint or Porter Ranch will happen; it’s where, and when, and how long a community will have to shout before someone hears them.

Like a negligent homeowner, the US is woefully behind on repairs to its most basic systems. Existing roads, bridges, ports, water systems, and other infrastructure need an estimated $1.6 trillion in upgrades, according to a 2010 report from the Department of Homeland Security.

Take a look just at the oil and gas sector. Drilling in California began a century ago. Only a tiny fraction of wells were safely sealed after their operators abandoned them for more productive or better constructed options. Today, the state is littered with 20,000 idle oil and gas wells.

Even active production and storage facilities are worryingly neglected. The gas well at Aliso Canyon was drilled in 1953 and converted to storage in 1973, without a single upgrade. The state regulator responsible for the wells has all but admitted that its inspection program is useless. The agency’s own report dated Oct. 8—less than three weeks before the leak’s discovery—found “outdated regulations that in some cases do not address the modern oil and gas extraction environment.”

“It’s been a long-standing concern that this agency is too close to the industry that it regulates,” said Briana Mordick, senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council. In California, the NRDC is lobbying for a complete overhaul of the regulatory system.

Infrastructure failures could cost the US $3.1 trillion by 2020, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) estimates. By their count, an annual investment of $157 billion a year could stave off the worst disasters. In an era of strapped budgets, the likelihood of states taking proactive action on a budget item that can almost always be convincingly delayed is slim.

It doesn’t help that most of the worst risks are in low-income communities, which typically have to fight a lot harder to be heard. While nobody should have to put up with environmental catastrophe on their doorstep, the response times for the disasters in California and Michigan are striking. The gas leak lasted four months in Porter Ranch, a predominantly white, upper-middle-class community.

In Flint, a lower-income, predominantly black city, regulators dismissed residents’ complaints of water that looked, smelled, and tasted bad for almost two years, even as scientists and doctors reported elevated lead levels in the water and the people who were drinking it. No one has been relocated. Flint is still charging residents for water that makes them sick.

“It’s a game of as long as its not happening to you, you don’t think about it,” said Casey Dinges, senior managing director at ASCE. “People can always convince themselves to do nothing.”