Why are Republican candidates vowing to spend billions on a troubled South Carolina nuclear plant?

Aiken, South Carolina

Aiken, South Carolina

Aiken isn’t big. The South Carolina county boasts only 164,000 people, give or take. But in the last four days—the homestretch of the state’s crucial Feb. 20 primary—all but one Republican presidential candidate swept through the area, the kind of attention counties twice its size can expect.

Stranger still, though, is Aiken’s uncanny knack for getting big-government-hating GOP candidates to promise big government spending.

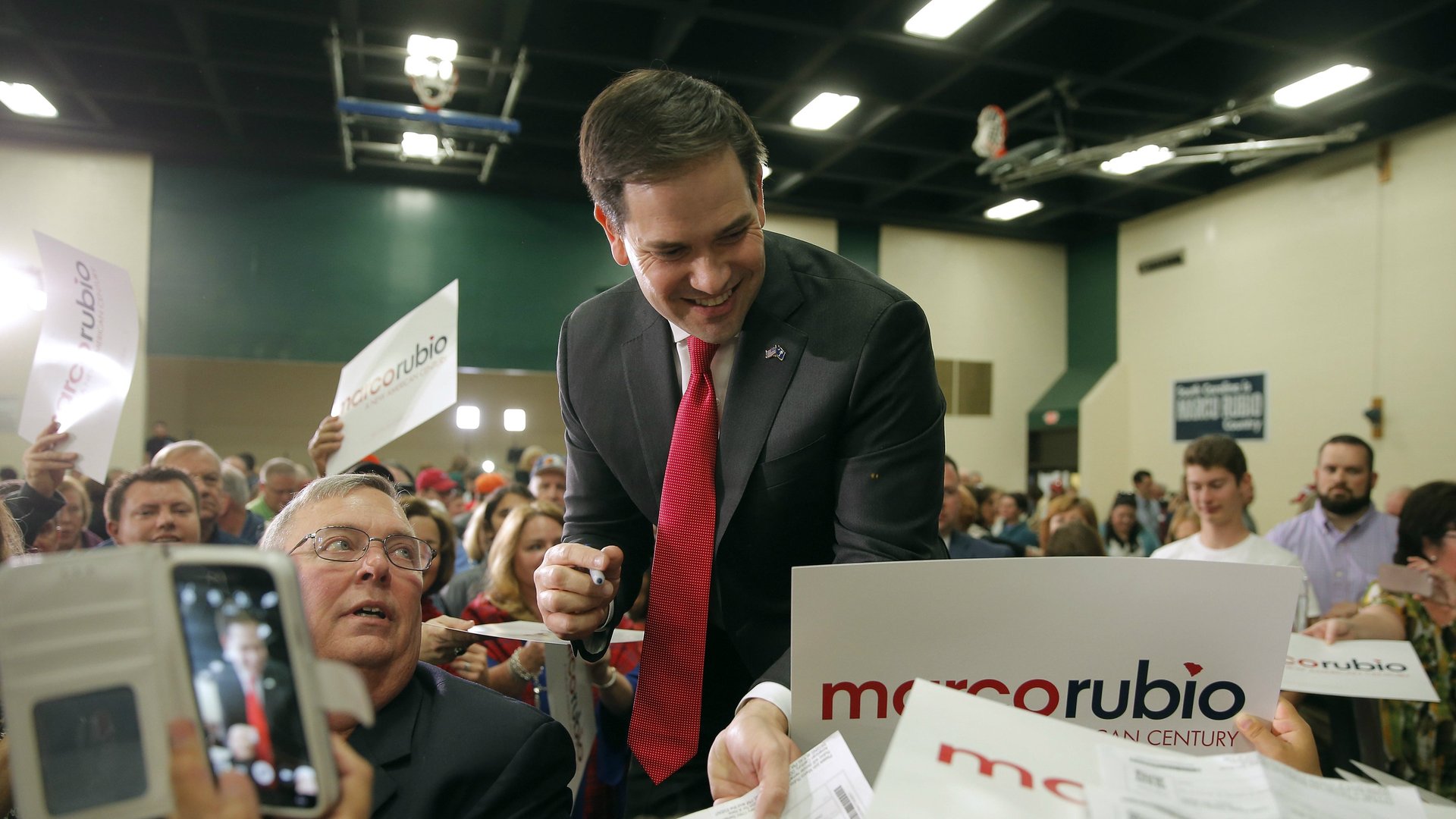

Take, for example, this scene from an Aiken gymnasium, where crowds hankering to see Marco Rubio swelled so big, they threatened to break the fire codes. Midway through, the Florida senator vowed to shrink the federal government’s size, saying, “today it’s involved in all kinds of things that really belong” to states and local communities.

Seconds after the perfunctory-sounding applause that followed, Rubio abruptly about-faced:

“Look what [the federal government’s] doing to this community now—the MOX facility. It refuses to fully fund it. It made a promise, people went out and spent money, and now they say we’re not going to give you the rest of the money. When I’m president we will fully fund and complete that facility.”

The crowd hooted its appreciation. This last bit was new material; the rest of Rubio’s speech differed little from the one he gave in Aiken in early January.

For the non-South Carolinians out there, “MOX” refers to mixed-oxide fuel fabrication, a way of turning weapons-grade plutonium into fuel for nuclear reactors. The federal government long ago named Aiken’s huge nuclear reserve the US’s sole MOX processor, and already has invested nearly $5 billion in its construction. After massive cost overruns and delays, the Obama administration now wants to shut down the project. Rubio opposes that reversal, as did rival candidates Jeb Bush and Ben Carson at an Aiken GOP forum on Feb. 16.

The MOX controversy is far more politically, er, explosive than the tech-speak makes it sound—a battle embroiling billions of dollars, oodles of Obama-hatred, interstate hostility, US-Russia relations, 34 tonnes of plutonium, and, ultimately, the fate of one of South Carolina’s biggest economic success stories.

Oh, and after this last week, the oaths of at least a few men who aim be America’s next president.

A brief history of MOX

When the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, most of America cheered. For Aiken county, however, its passing was bittersweet. Making nuclear weapons had been a crucial part of its economy since the 1950s, when the US government chose the area as a special site for making America’s atomic arsenal, christening the project the Savannah River Site.

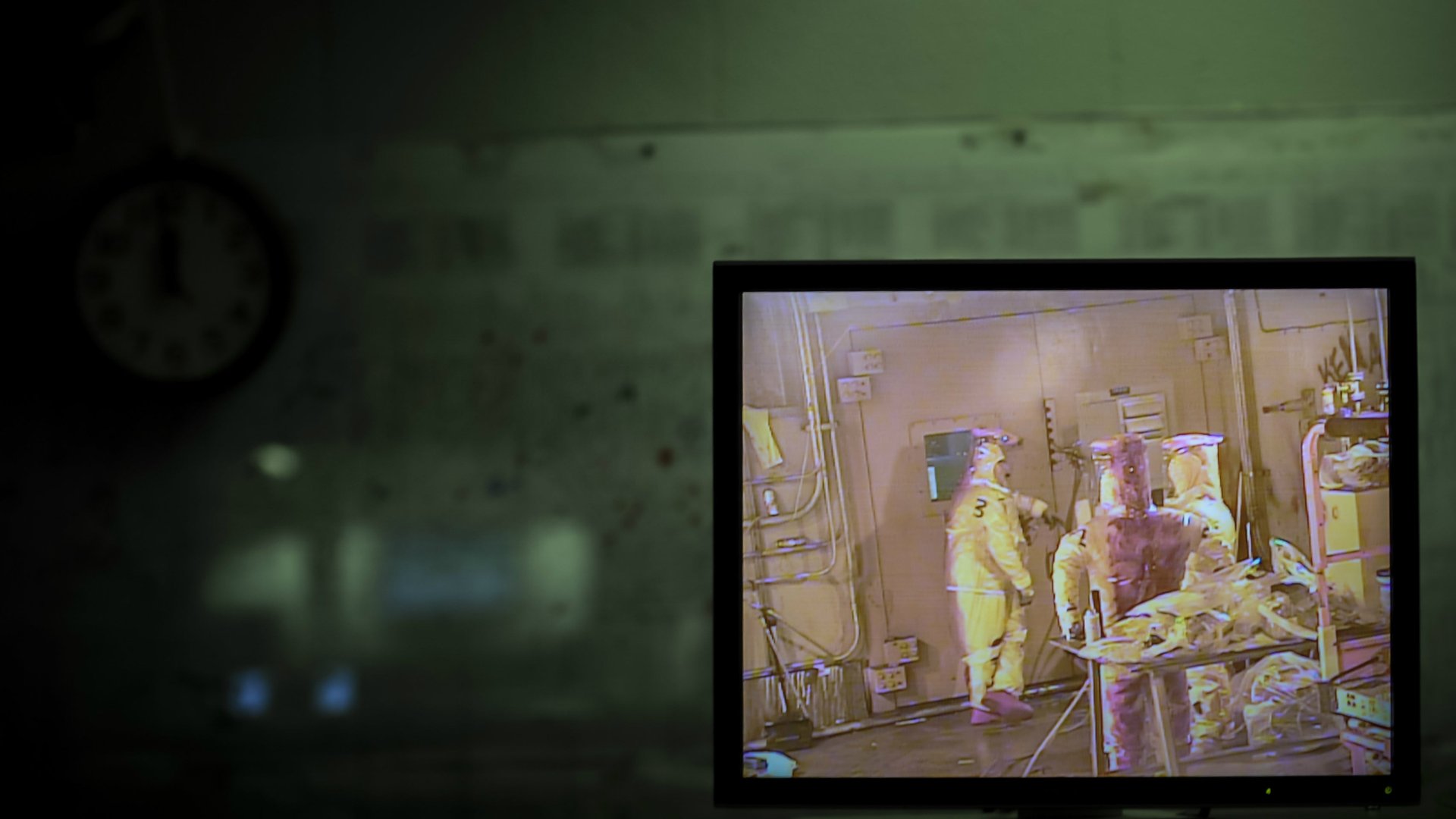

Then in a 2000 arms control deal, the US and Russia agreed to get rid of 34 tonnes (37.5 tons) of each country’s weapons-grade plutonium—about 17,000 nuclear warheads worth of nuclear material. The US slated the Savannah River Site to process the nuclear material, choosing MOX as its method. When the government finally started building the project, in 2007, the plan was to have the MOX facility up and running by Sep. 2016. The final price tag was calculated at $4.8 billion.

The feds miscalculated, big-time. The project isn’t close to being done—even with $5 billion already invested, reports Derrek Asberry, who covers the Savannah River Site for the Aiken Standard. It will cost between $800 million and $1 billion a year alone to complete, says the energy department, not counting staffing and operations costs. It could be higher; one estimate by a federally funded research group puts the lifetime cost as high as $51 billion. On top of that, it’s not clear who would buy the converted nuclear fuel. The longer it takes, the more likely it is that technology improvements will lower costs of commercial nuclear fuel.

Obama breaks out the mothballs

After years of trying to freeze project funding, the Obama administration slashed funding (pdf, p.3) for the Savannah River Site’s MOX project construction in the budget it released in early February. Instead, it opts to dilute the plutonium and ship it to storage facilities in New Mexico, a move the energy department says will be faster and less expensive.

That, of course, means halting the Aiken MOX project—which will put the majority of the 2,000 people now employed at it out of work. While that might not sound like a lot, for a small county, such a sudden loss of income threatens the entire economy.

Much ado about MOX

Many of South Carolina’s leaders are no less outraged. Among the biggest MOX-proponents are its two senators, Tim Scott and Lindsey Graham. It’s probably no coincidence that the best-connected candidates also happen to be well versed in MOX. On Feb. 17, hours after Rubio’s anti-MOX tirade, Nikki Haley—the state’s well-liked Republican governor—joined Tim Scott in endorsing the Florida senator. After dropping out of the GOP presidential race, Graham backed Bush.

Still, with so many issues to keep track of, why go through all the trouble for a mid-sized county? This is in part because its relatively high proportion of highly informed GOP voters—namely, its sizable population of old money, government workers and retirees—says K.T. Ruthven, president of Aiken’s Republican Party who is running for a seat in the statehouse this year. Since the primary began in 1980, Aiken county has chosen the eventual nominee every year except 2012, when Newt Gingrich beat Mitt Romney in the state primary, he says.

With such an engaged base, it’s no wonder that another vehement MOX advocate is Joe Wilson, Aiken county’s congressional representative. (Wilson is best known internationally for crying ”You lie!” at Obama as he addressed Congress in 2009.) One reason to keep Savannah River Site’s Mox facility going, argues Wilson, is that shuttering it would cost $500 million. Another is that Obama’s plan would require renegotiating with Russia—something that, with US-Russian relationships on the fritz, might be tricky.

However, the World Nuclear news reports that Russian leaders say such an agreement is “not needed.” Complicating matters even more is that Wilson’s biggest donors include the two companies that own the MOX facility’s principal contractor, as the New York Times recently reported (paywall).

Haley’s counterstrike

The governor, however, was planning an attack of her own. Even as the Obama administration prepared to cut the Mox facility’s funding, Haley had asked Alan Wilson, South Carolina’s attorney general (and son of Joe Wilson), to sue the energy department for failing to pay fines owed to the state for missing project milestones. The suit hinges on a 2003 agreement whereby the department was to have processed 1 tonne of plutonium by Jan. 1, 2016, or have shipped that amount out of state. The penalty is $1 million a day, capped at $100 million a year. As of today, the feds are almost halfway to that cap.

It’s unclear where the lawsuit will lead. However, even if South Carolinian Republicans manage to foil the Obama administration’s MOX-cutting, it may be a long time before Aiken residents are content with the federal government’s nuclear policies.

The battle of Yucca Mountain

It gets worse, though. MOX isn’t even the only nuclear controversy roiling anti-Obama sentiment in Aiken. In addition to the 34 tonnes of weapons-grade plutonium that’s still sitting around, there’s also more than 36 million gallons of readioactive waste, the byproduct of the bombs once made there, sitting in aging tanks. One local government official recently called these the “single largest environmental threat in South Carolina.”

This waste wasn’t supposed to stay in South Carolina. Instead, it was to go deep in a tunnel that the energy department began boring into Nevada’s Yucca Mountain in 1994. In fact, one-tenth of the $13 billion invested in the Yucca Mountain project came from South Carolina taxpayers, spent under the assumption that the Yucca would soon take its nuclear waste away.

That never happened, though. Citing safety fears, in his 2008 campaign, Obama said the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste disposal efforts were “an expensive failure and should be abandoned.” The project was scrapped in 2010. It’s widely suspected that the administration was responding to the political priorities of Harry Reid, the Democratic senator whose Nevada constituents didn’t want to harbor other states’ nuclear waste.

Why Aiken loves George W. Bush

Of course, the Savannah River Site has benefited the community hugely, providing not just jobs, but also helping to fund educational institutes and train a workforce skilled enough to attract companies like Japan’s Bridgestone tires to the area. But Aiken’s relationship with the site is fraught with tension, straining between gratitude for the wellbeing it has created and the precarious state in which it leaves the community.

It’s not just that Aiken’s economy is vulnerable to the whims of the feds. Imagine living next to a gargantuan cache of atomic gunk. Even though scientists deem the Savannah River Site safe, its presence is still unsettling. This is one element of why the area loves former president George W. Bush so much, says Jane Page Thompson, a Republican community activist in Aiken. When terrorists plane-bombed the World Trade Center and Pentagon, anxiety ran high. The locals’ concern is that a federal nuclear facility such as theirs would be an obvious target for any terrorists targeting the US.

“Because of [Savannah River Site], we know we’re on that list,” Thompson tells Quartz, adding that what Aiken residents saw as Bush’s calm, decisive action made them feel safe.

If Obama’s new plutonium-conversion plan isn’t quite as swift and efficient as he thinks—or if the bureaucratic dithering continues—the nuclear material will stay at Savannah River indefinitely. And the longer it does, the longer Aiken residents must live with that nagging existential dread of a local reprise of the 9/11 attacks.

No nuclear exit strategy

In a sense, Aiken has unfairly become the default storage facility for both sources of nuclear material, says Will Williams, president and CEO of the Economic Development Partnership, an industrial recruitment organization for Aiken and nearby communities.

“There’s no exit strategy for the material…. Meanwhile the Obama administration through no other reason besides politics came to cancel Yucca Mountain,” Williams tells Quartz. “That’s what this election is about—we want to see someone who will maintain the Department of Energy facility.”

That priority helps explain the unusual consensus that gels among Aiken GOP primary voters—the one that K.T. Ruthven mentioned. This focus makes sense. The next US president could indeed help grant Aiken a glimpse at its post-nuclear future. Or the status quo may linger. After all, the commitments brokered in the Oval Office never come as easily as on the campaign trail.

Flickr images used above are courtesy of the Savannah River Site Flickr page (licensed under CC BY 2.0; images have been cropped).