Here’s how America’s confusing and outdated rape statutes of limitations are hurting victims

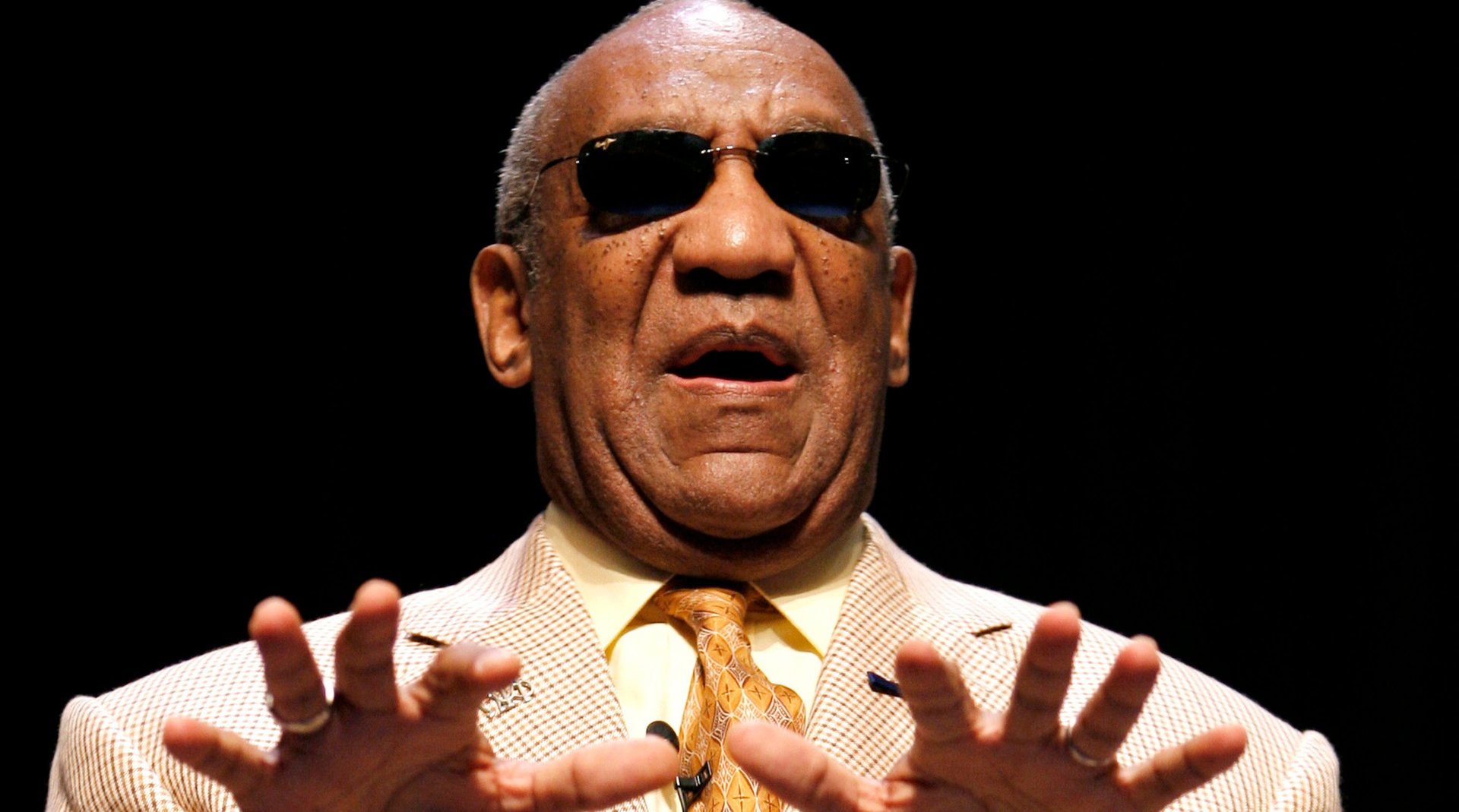

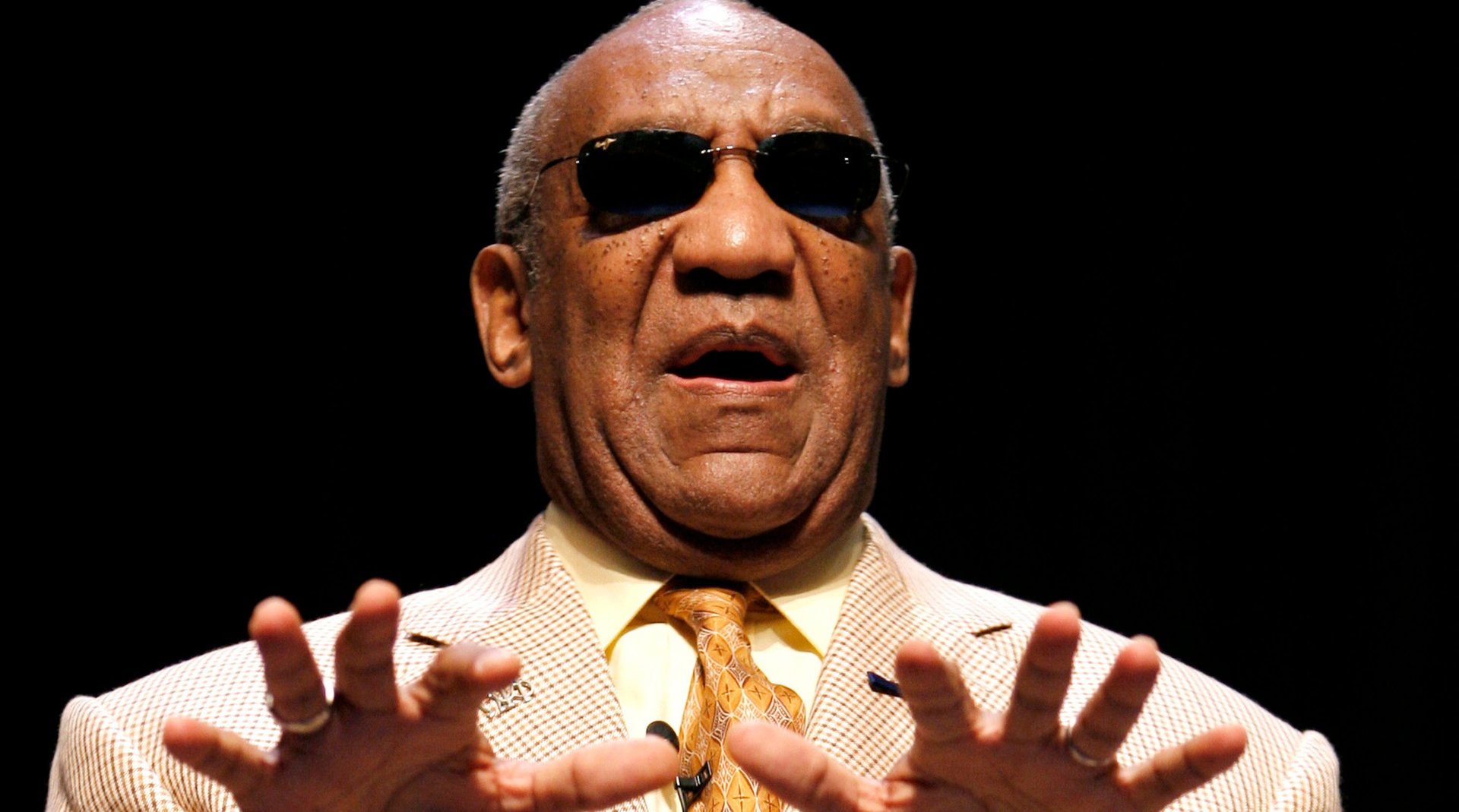

As I watched multiple allegations of rape against Bill Cosby accumulate, I did what every legal geek would do: I checked the statutes of limitations. Because the women who accuse Cosby of sexual assault hailed from various jurisdictions, and because statutes vary depending on the state, geography could play a deciding factor in whether Cosby was tried in the court of public opinion, or a court of law. When charges were finally brought against Cosby in Pennsylvania on Dec. 30, 2015, for a crime first reported in 2004, the prosecutors squeaked in just under the 12-year mark.

As I watched multiple allegations of rape against Bill Cosby accumulate, I did what every legal geek would do: I checked the statutes of limitations. Because the women who accuse Cosby of sexual assault hailed from various jurisdictions, and because statutes vary depending on the state, geography could play a deciding factor in whether Cosby was tried in the court of public opinion, or a court of law. When charges were finally brought against Cosby in Pennsylvania on Dec. 30, 2015, for a crime first reported in 2004, the prosecutors squeaked in just under the 12-year mark.

In North Carolina, where I live, there is no statute of limitations for felonies at all—including sexual assault. North Carolina is one of 16 states that allow a sexual assault survivor to report the crime solely on the survivor’s timeline, rather than the timeline of the statutory code. These statutes limit the amount of time a victim has to come forward. Once the statute has expired, the state no longer possesses jurisdiction over the crime. Expiration of the statute has no bearing on an alleged perpetrator’s innocence, of course. And research shows that in sexual assault and sex-based violence cases, it’s common for a considerable amount of time to elapse before a victim comes forward.

Recently, in light of the sole prosecution against Cosby—and the marked lack of prosecution for the other alleged crimes he committed—Jill Filipovic argued that the remaining US states should get rid of their statutes of limitations for sexual assault. Writing in The New York Times, Filipovic argued that the singular nature of the crime of sexual assault—including the known reticence of its survivors, the foot-dragging of police and prosecutors, and the backlog of rape kits—is reason enough to change the law.

As a former lawyer, I know it’s a bit more complicated. And yet Filipovic has a point, especially when you consider the inconsistent nature of statutes of limitations nationwide. Why, for example, does Colorado reserve the right to prosecute an alleged forger forever, but not an alleged rapist of an adult woman? Why do rape victims have their entire lives to seek justice in Texas, but only a decade in California? How do we weigh the public policy reasons for having statutes of limitations against the very real difficulties faced by many sexual assault survivors?

This isn’t to say statutes of limitations serve no purpose. Richard E. Myers is a former defense attorney, former federal prosecutor, and current professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law. Myers tells Quartz that there are practical, and socially beneficial, reasons why statutes exist for other crimes. For one thing, the quicker the trial, the more (potentially) accurate the prosecution can be. “The prosecution wants a [statute of limitations] because it encourages prompt action,” he says. “We want to encourage the investigators to act and witnesses to come forward in a timely fashion.”

The second reason concerns fairness. “If you allow a case to get really old, it skews heavily in the prosecution’s favor,” Myers tells Quartz. “The defense is more likely to lose witnesses than the prosecution.” The third reason also relates to fairness, but with a social justice tilt: “We believe in fresh starts. We believe in people rehabilitating. Going back twenty years [to prosecute a crime] … feels unfair to many people. People should be judged on the basis on who they are now.”

But what about sexual assault or sex-based crimes? Is there something unique about these crimes that merits lengthening the statutes of limitation, or, as Filipovic argues, scrapping them altogether?

According to Sherry H. Everett, an award-winning domestic violence attorney and adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law, yes–there absolutely is.

Sexual assault or abuse victims often take longer to come to terms with their own crimes, a problem rooted in society’s longstanding prejudice against rape victims. “A big part of the victimization of women—all kinds of victimization and abuse—includes the perpetrators convincing her that she’s not actually a victim, that she’s crazy for thinking the perpetrator has done anything wrong,” Everett tells Quartz. These feelings often lead victims to wait to report crimes, especially when the perpetrator is not a stranger.

Indeed, women often have trouble asking Everett for help, saying: “I don’t know if I need a lawyer. I don’t know if I should be in court right now.” Everett notes that self-doubt among victims is very common. “I’ll get a description of a horrific victimization that a woman has undergone. And her next line is either: ‘Did I bring this on myself?’ or ‘I played a part and we’re both wrong,’” she says. “And we’re talking about clearly illegal, black-and-white behavior on the part of the perpetrator.”

The high degree of self-doubt, coupled with feelings that the victim is somehow also to blame, is somewhat unique to sex-based crimes and sexual violence, according to Everett, and to multiple studies on sexual assault victimization.

A longer statute of limitations, according to Everett, “would give community agencies, such as rape crisis centers, time to support victims and get them to a point where they’re ready and able—emotional, mentally, financially—to come forward and report a crime.” Everett also made the point that many rape victims are “financially dependent on their rapists,” and may need time to become financially independent before taking any legal action. In a state with a short statute of limitations on sexual assault crimes, however, a victim might not have that kind of time.

In the example of Cosby, newly elected district attorney Kevin Steele finally chose to bring charges on a crime that a victim first reported in 2004. Cosby’s legal team has repeatedly attempted to stall and dismiss the case, but as of Feb. 17, Montgomery County Judge Steven O’Neill has ruled that the case should continue to trial. Everett notes that just as in any other crime, a DA can choose not to prosecute. But the limited timeline presented by statutes of limitations can be very disempowering for victims.

Case in point: In 2005 then-DA Bruce L. Castor Jr. declined to bring charges against Cosby, claiming there was insufficient evidence to prosecute. Here we have a situation in which the victim reported a sexual assault crime in a timely fashion. But the justice system dragged its feet, nearly allowing the statute of limitations to expire. In a jurisdiction with a shorter statute of limitations, charges might never have been brought.

Ultimately, the problem isn’t statues of limitations. It’s that the US legal system still has not wised up to the unique factors that complicate sexual assault and other forms of sex-based violence. These factors include the status of the victims, who may feel ashamed or may live dependent on their abusers. Then there are the very real dangers posed by poorly trained police, evidence obstacles (including an enormous rape-kit backlog), and doubtful prosecutors. These challenges create a very real barrier between justice and the victims of crimes that generally do not exist when dealing with, say, allegations of auto theft.

We need to have a national conversation about whether rape charges should be treated like murder cases—that is, without the constricting effects of a statue of limitations. And quickly. Because when weighing the legal implications of statutes of limitations against the needs of this particular class of victims, it becomes clear that, for this particular crime, justice cannot adequately be served under the pressures of a ticking clock.