Can “Potato Sister,” a singing peasant, convince the Chinese to eat more of the lowly spud?

One of China’s newest academic offerings is a very specific affair—the Potato College at Yunnan Normal University in Kunming will offer majors in potato genome studies, or potato genetic breeding. The university, in China’s southwest, already has a living germplasm bank which contains a gene database of 1,200 of the world’s 5,000 or so varieties of potato. This summer, Kunming will also host China’s sixth Potato Expo.

One of China’s newest academic offerings is a very specific affair—the Potato College at Yunnan Normal University in Kunming will offer majors in potato genome studies, or potato genetic breeding. The university, in China’s southwest, already has a living germplasm bank which contains a gene database of 1,200 of the world’s 5,000 or so varieties of potato. This summer, Kunming will also host China’s sixth Potato Expo.

It may seem like overkill, but the developments in Kunming are the latest evidence of the potato fever sweeping through China’s agricultural ambitions.

Potatoes consume 30% less water to grow than rice or grain, China’s favorite staple crops, and increasing production could help alleviate some of the severe water shortages affecting the country—projected to become more acute in the years to come. China is already the world’s largest producer, with 5.3 million acres of land dedicated to its production. But the government aims to nearly double this by 2020.

The unloved spud

The real challenge lies in making Chinese consumers eat the spud, which is often associated with poverty, as it was one of the few types of food available during the famine years of the last century. The unlikely current star of this push is Feng Xiaoyan, a 52-year-old Shanxi “peasant” with a passion for singing.

Feng, or “Sister Potato” as she is known on her Weibo page, has been making appearances on national TV to explain how potatoes are “great for nutrition and countering desertification” and to take part in numerous variety shows.

Here she can be seen singing and explaining (video in Chinese) the wonders of the spud, on China’s prime video-sharing site Tudou (the name, coincidentally, is Chinese for “potato”).

Chinese people often take with relish to foreign culinary imports–in ways that go deeper than the current success enjoyed by international fast-food chains. Imagine Sichuan without chilies, your favorite stir-fried dishes without peanut oil, or any Chinese student canteen without the perennial eggs with tomatoes, and you have Chinese cuisine before the Portuguese and the Dutch brought New World crops over to Asia, about four centuries ago.

The potato, however, also from the Americas, has made less of a culinary impact, because of its famine-era associations. The exceptions are few.

You may order lajiaotudousi—julienned peppers and potatoes stir-fried in vinegar, garlic, and peanut oil, with a sprinkling of chilies and the occasional Sichuan peppercorn everywhere. Or find a bed of potatoes in some versions of yuxiangqiezi—a rather delicious, if greasy, eggplant dish. But by and large, potatoes have not seduced Chinese chefs much, and are more regularly seen as containers once they have been shredded, molded into baskets and fried, than as full-blown ingredient.

A ‘new peasant’

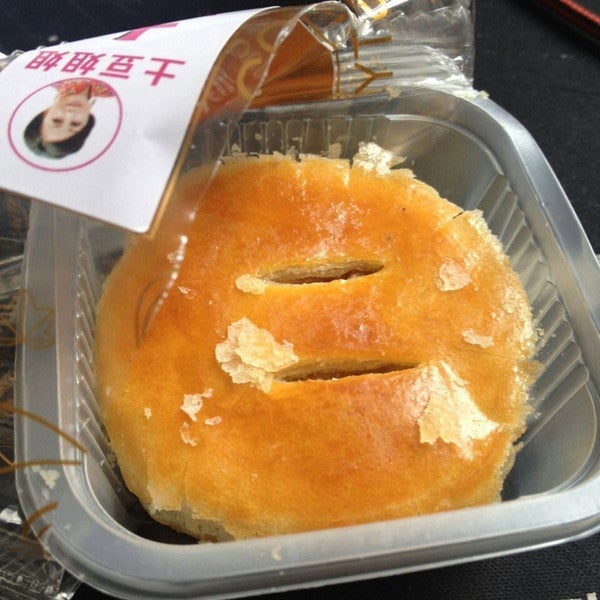

Feng is trying to change this by also peddling potato cakes—on China’s massive online shopping site Taobao—made from organic potatoes grown in the Shanxi province, and presenting them as a luxury treat (left). Fancy packaging and lavish pictures portray potato cakes as a festive dessert, healthy and full of nutrients.

Once a teacher and a businesswoman, Feng now defines herself as a “new peasant.” This apparently means a farmer who uses old and new media to spread her message—“eat more potatoes!”

After four years working in “Party and government-related positions,” she decided to go full-potato in 2010 after successful experiments showed that the spud can grow on barren land, explains a profile of her (link in Chinese) by online agricultural magazine Enongzi.

“Potatoes are flowering in the desert,” she often sings in an operatic voice. Potato by-products, such as noodles, flour, and bread, are the future. “Great opportunities just burst forward from small potatoes,” as she told Enongzi.

Agricultural shifts

While Feng sings the potato’s praises, China’s ministry of agriculture has made technological advances that have found how to turn the starchy water into more fertilizer, for yet more potatoes.

China already exports 6.5% of the world’s raw potatoes:

The agriculture ministry classifies potatoes as a grain, and demand for grains overall is booming. China’s total demand for grain (pdf, pg 27) is expected to hit 700 million tons a year in 2030, the World Bank estimates, and may have already outstripped supplies grown in the country.

If the government has its way, as it normally does, China will be eating more potatoes shortly to meet increased food demand.