Your checking account is probably easier to hack into than your email

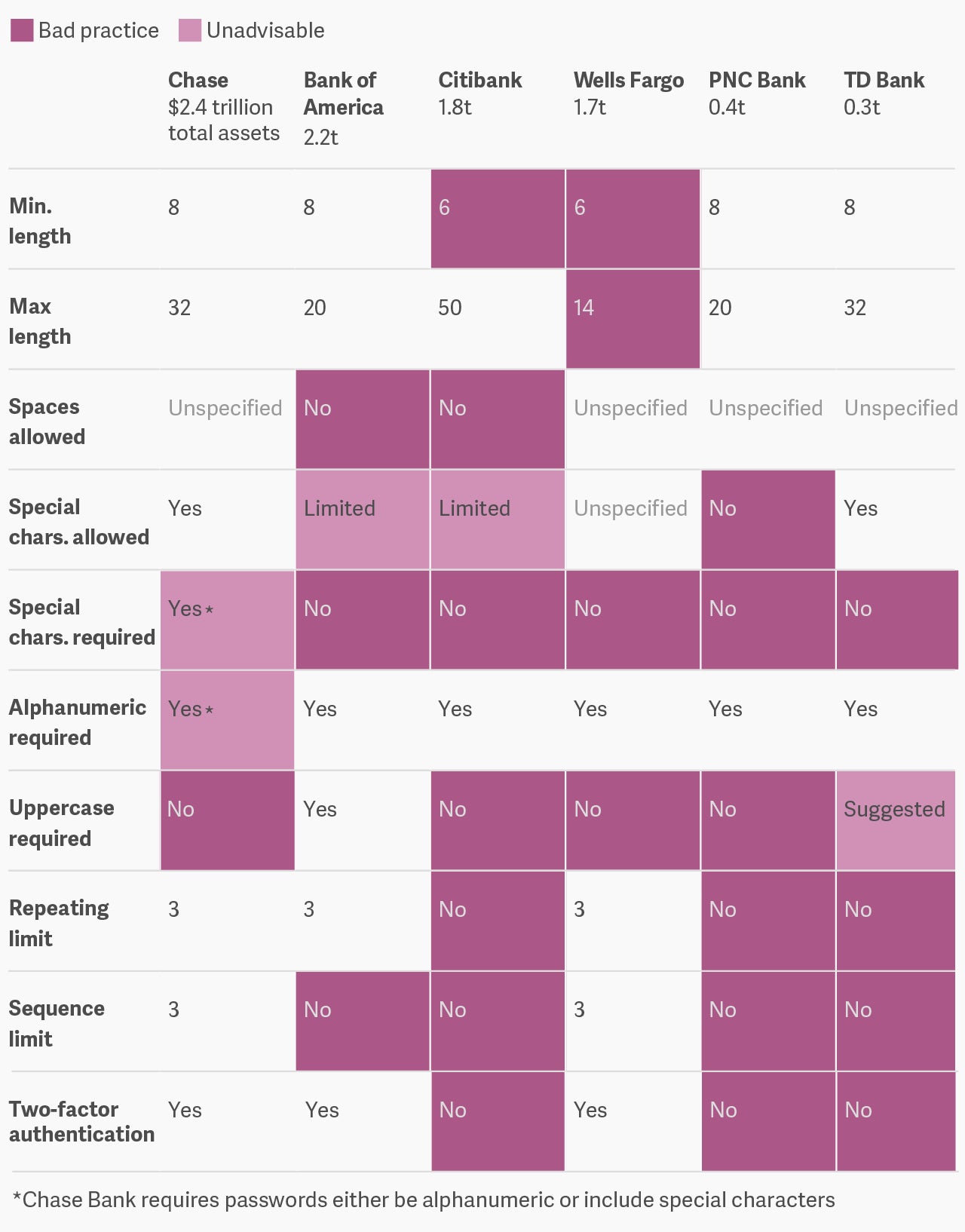

Few passwords are as important as those that protect your finances. So you’d expect banks to require the most secure login credentials on the web, but that is largely not the case. We checked the password requirements at six of the biggest consumer banks and found that they allow pretty simple passwords across the board. We also found that only half of them provide two-factor authentication.

Few passwords are as important as those that protect your finances. So you’d expect banks to require the most secure login credentials on the web, but that is largely not the case. We checked the password requirements at six of the biggest consumer banks and found that they allow pretty simple passwords across the board. We also found that only half of them provide two-factor authentication.

Based on these requirements, here are the simplest possible passwords we could come up with that each bank would apparently accept:

- JPMorgan Chase: Abc098xy

- Bank of America: Qwerty12

- Citibank: a12345

- Wells Fargo: aaa111

- PNC Bank: aaaaaaa1

- TD Bank: password1

None of these banks explicitly require special characters, like !, @, # or $. Of all of them, the Chase password is the strongest. Chase Bank doesn’t allow common passwords, such as ”password1″. That makes it the only password on this list that hackers might not be able to instantly crack.

But what does it mean to crack a password? Do hackers spend their days opening up bank websites and typing in a bunch of random numbers and letters at the login screen? Perhaps in the earlier days of the internet, but not in 2016. These days, attackers prefer to deal in bulk.

Let’s say there’s a data breach at your bank, like the one at JPMorgan in 2014. The 83 million records stolen in that incident did not include online banking login credentials, but let’s imagine the breach at your bank did. In all likelihood, the passwords stolen in such an attack would probably be encrypted. The first thing a group of hackers might do with encrypted passwords is check them against a “rainbow table.” These are enormous databases that include encrypted, or “hashed,” versions of almost every conceivable password up to a certain length, along with the password itself in plain text.

Hackers can simply check the encrypted passwords in their stolen database against those in their rainbow table, and pull out the passwords of every match in plain text. If the passwords are anything like the basic ones we came up with above, there will almost certainly be an instant match. Since JPMorgan Chase doesn’t allow common passwords, those might be less likely to match a password in a rainbow table. And if there’s no match for a given set of passwords, the hackers would have to start guessing.

To decrypt passwords by brute force, they’d have to let their computers iterate over millions of possibilities over days or even months, but that scenario isn’t outside the realm of possibility. After the infamous data breach at Ashley Madison last year, researchers were able to crack the encrypted passwords for 11 million of the 36 million breached accounts within a few weeks. The passwords they couldn’t crack so quickly were those that were longer and more complex.

The trick is to use passwords that are long and complex enough that they’d take too long for hackers to bother to crack.

It’s also important to use a unique password for every website, no matter how innocuous or unrelated to finances that website may seem. If you use the same login credentials for multiple websites, a breach of any of those accounts puts them all at risk. Consider the 145 million customer records stolen from eBay in 2014. Those also included encrypted passwords, along with email addresses. How many login credentials from eBay, once cracked, could also get into bank accounts?

According to security researcher Marcus Ranum, this is a common problem that can often lead to a worst-case scenario. Even if the stolen credentials don’t get attackers directly into bank accounts, what if they can get them into email accounts?

“Now the hacker has the user’s [email account] and can use that address to reset passwords on everything,” Ranum said, “including online banking.”

So the cases in which it will matter that you use a weak password for online banking are 1) if your bank itself is hacked and its passwords are stolen, or 2) if you use the same weak password on other websites, and one of those is breached. There’s also the less common case, in which a hacker is targeting an individual. When an attacker has only one target, they can do research on the subject to come up with their most likely passwords, and try a couple each day until they get a hit.

The first step in improving password security, of course, is to add characters. For each extra character in a password, the longer it will take to crack, and the less likely hackers will be to take the time to guess it. The second step is to use a different password for every site. There are password management apps that make that easier. They can use randomly-generated passwords up to the maximum length a website will allow. Based on our survey of password requirements, that could make bank passwords look more like this:

- JPMorgan Chase: Y>0Rx}9SpbU-‘DzdBXHRelP)[N]t84k{

- Bank of America: #Qjiks38NL*+MORx7kA+

- Citibank: YqQH9UEkj.0@Lr85MSv4x1_.NZKYWXx@48hss5_mBV.vNc@MiY

- Wells Fargo: C!e1PaY4Drl%_R

- PNC Bank: wM8bCbUdvEt3w2bwypty

- TD Bank: rLQkJhc7p8*NDr%GE4sL3*D8S^OT*9Ce

Wells Fargo’s limit of 14 characters remains a liability here, as does PNC Bank’s failure to allow special characters. But at their most complex, both would be good enough to protect your account from hackers in most cases. Using a password management app also leaves out passwords that someone might guess, like the name of a pet or a birthday.

Those two steps will make your bank login pretty secure, but according to Ranum, two-factor authentication is also essential. Many Gmail users will be familiar with this process, since Google started aggressively pushing it a few years back. Any time you sign in from a different device, the website will text or email you a code that you type in, to prove you are you. (Ranum, by the way, suggests you opt for SMS verification rather than email.)

The problem is, most banks still don’t provide true two-factor authentication. Of the six banks we looked at, only three of them provide it. Think of it this way: if you have two-factor authentication setup on your Gmail and not on your online bank account, it’s theoretically easier for hackers to access your checking account than your email. And that’s just silly.

The last thing to keep in mind is that all of your accounts are only as secure as your computer or smartphone. As the web standards advocate John Pozadzides told Quartz, an attacker could always just steal your phone.

“Most people are always logged into their email, and they usually don’t lock their phone,” he said. “If I had your phone, not only could I get into your email, but I would also be able to confirm 2 factor authentication via SMS to your phone number.”

Update: Wells Fargo has just introduced two-factor authentication over the past month, which customers can opt into. The details the bank has online are a little vague, but a spokesperson told Quartz: “Now all online/mobile customers have the option of enrolling in the service, where we’ll send them an access code each time they log on.”

Correction: The chart above originally labeled the bank assets in billions rather than trillions. It also said Chase Bank requires special characters, but it actually only requires either special characters or alphanumeric passwords.