This venn diagram explains Bernie Sanders’ unique appeal

Bernie Sanders’ dislike of banks is well known, but in a world full of politicians eager to blame banks for your problems, he literally stands alone.

Bernie Sanders’ dislike of banks is well known, but in a world full of politicians eager to blame banks for your problems, he literally stands alone.

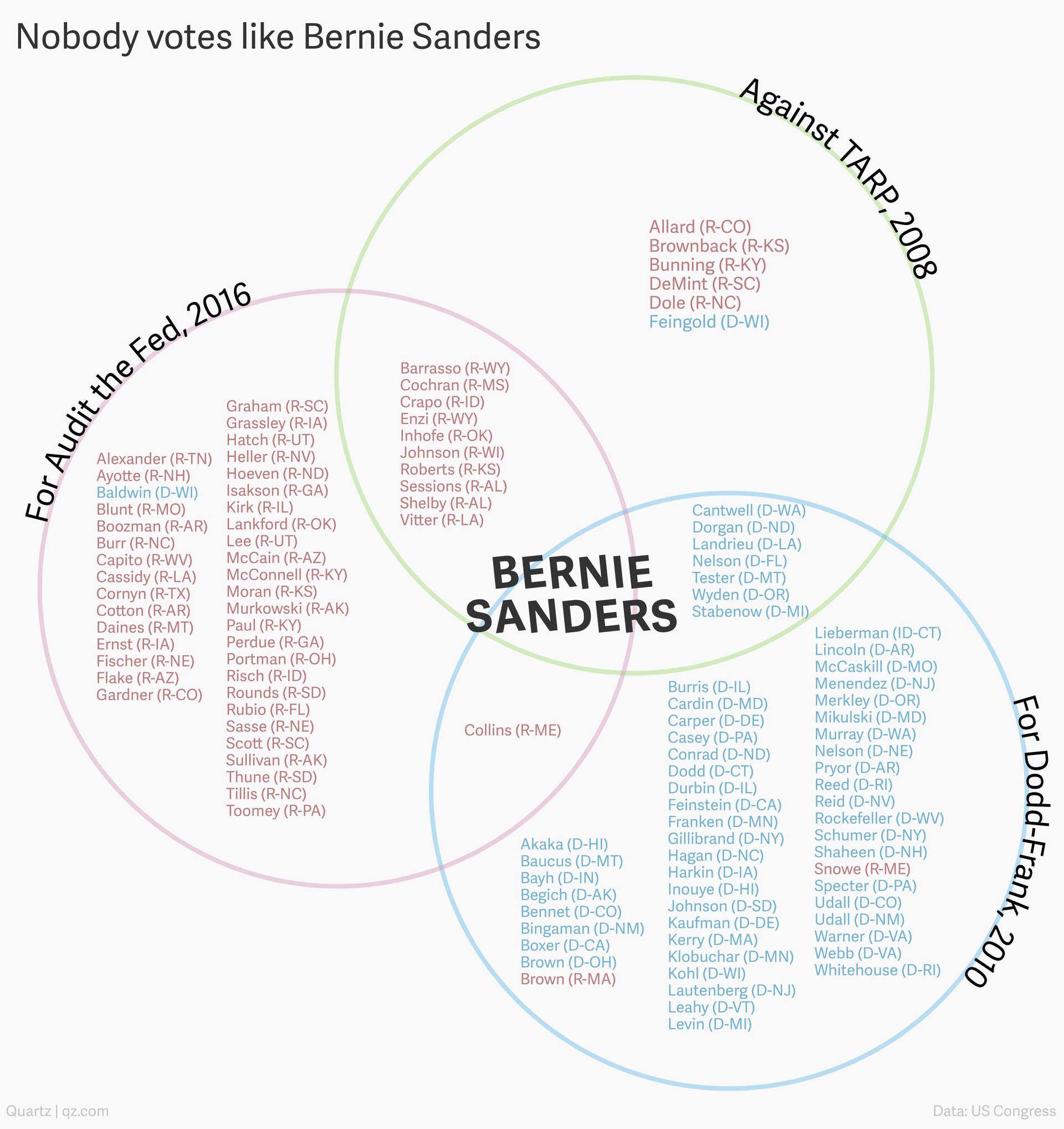

Menzie Chinn, a University of Wisconsin economist, put together an instructive diagram based on how senators voted on three key laws—the 2008 Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) bill to bail out the banks and the auto industry; the 2010 Dodd-Frank bill that imposed new rules on banks, ostensibly with an eye toward preventing the next crisis; and a 2015 vote on a bill to audit the Federal Reserve.

Sanders is the only senator to oppose TARP while supporting the other two bills. We’ve replicated the diagram here:

You may need a refresher to understand the splits the diagram reveals, so let’s go around the horn clockwise.

In 2008, TARP was easy for anyone to hate—even its supporters saw the bill as necessary evil—and the senators who voted against it represented a bipartisan coalition of Wall Street skeptics who either thought that a bailout was unnecessary or that this particular one had too few strings attached.

By 2010, when Dodd-Frank came up for a vote, the result was largely along party lines. Many Democratic lawmakers were eager to back a bill that Wall Street fought against with a passion, knowing it increased capital requirements and put in place other restrictions on risk that would cut their profits. Its Republican opponents thought the crisis showed a need for less government supervision of the financial crisis, not more.

Finally, in 2015, a bill authored by libertarian senator Rand Paul to audit the Federal Reserve came up for a vote. More than an effort to increase transparency at an institution that quickly got religion on transparency under former chairman Ben Bernanke, the proposed legislation mandated reviews of Fed policy decisions and demanded more predictable monetary policy. Right-wing supporters of the bill view the Fed’s concentrated power as a threat to US economic stability and back hard-money policies like the gold standard, while left-wing supporters see the Fed as too influenced by the financial sector. Those who opposed the bill fear that a Fed subject to political whims will do a bad job setting monetary policy.

Ultimately, seven Democrats joined Sanders in backing Dodd-Frank after voting against the TARP, seeing its rules as a way to prevent future bank bailouts like they kind they opposed. Eleven Republicans who opposed TARP and D0dd-Frank backed the effort to audit the Fed—get the government out of the way and let the financial sector do its job, thanks. And one moderate Republican, Maine’s Susan Collins, supported TARP, Dodd-Frank and Audit the Fed.

Only Sanders struck the populist trifecta, though: Opposing the bailout for banks, supporting new rules to restrict them, and demanding more influence over the technocrats at the Federal Reserve. This streak of principle obviously endears Sanders to his backers. It also raises the question: Is he the best person to build a coalition around financial reform, or the worst?