A short guide to supercookies: whether you’re being tracked and how to opt out

Verizon, the largest US wireless carrier by subscribers, was slapped with a $1.35 million fine by the US Federal Communications Commission yesterday (March 7) for its use of “supercookies” that track users’ web browsing activity without their knowledge.

Verizon, the largest US wireless carrier by subscribers, was slapped with a $1.35 million fine by the US Federal Communications Commission yesterday (March 7) for its use of “supercookies” that track users’ web browsing activity without their knowledge.

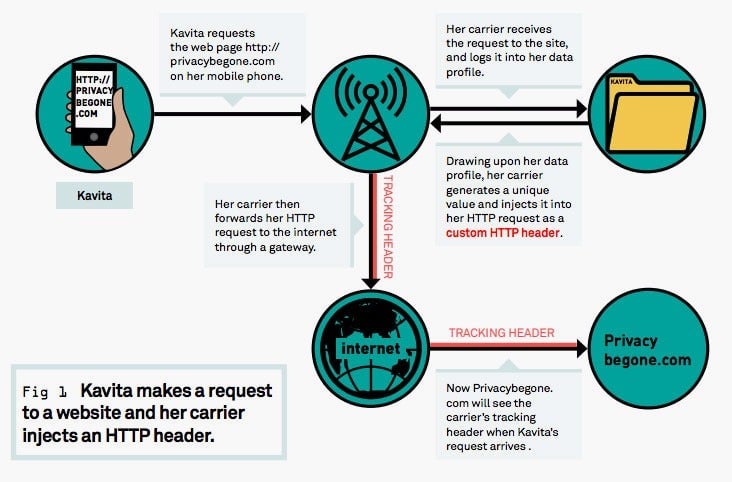

The terms “supercookies,” “permacookies,” or “zombie cookies”—as these trackers are commonly referred to—are a bit of a misnomer. Unlike regular cookies, which are bits of data stored locally on a device after being downloaded from websites, “supercookies” are not cookies at all. The Unique Identifier Headers (UIDH) used by Verizon were injected at the network level when users visited websites over an encrypted connection.

Here’s a brief guide to how tracking headers are used, where they’re found, and how to opt out.

Tailored advertising

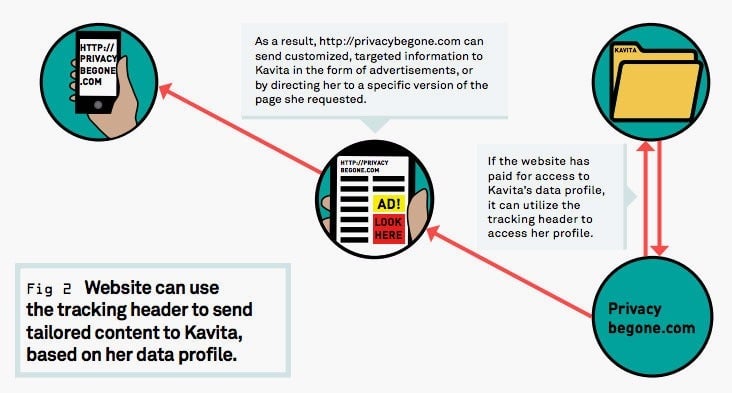

Tracking headers identify people’s web behavior by building up a profile of unencrypted sites (those sent over HTTP) that they visited. Third parties that pay for access to these profiles can then use that data to send targeted information, such as advertisements, to people. But because all this information is injected every time a user makes an HTTP request, sites can easily detect if there’s a tracking header. So, even if the carrier doesn’t sell data collected from supercookies to advertisers, third-party firms can independently identify the supercookies for advertising purposes.

Carriers

According to an online test by Access Now, an organization that advocates for digital rights, supercookies have been used for at least a decade and are most prevalent in the US, followed by Spain and the Netherlands. They have also been found in Canada, China, India, Mexico, Morocco, Peru, the Netherlands, and Venezuela.

Of 180,000 results returned from a test created by Access Now, 15% showed the presence of tracking headers. In the US, the two largest carriers, Verizon and AT&T, have deployed these tracking headers, though AT&T said in 2014 that they were “phased off our network.” Other mobile carriers that have used tracking headers include Bell Canada, Bharti Airtel, Cricket, Telefonica de España, Viettel Peru, and Vodafone, according to Access Now.

Potential security risk

Access Now notes that some supercookies can leak users’ information, such as phone numbers. While there hasn’t been evidence suggesting criminals have taken advantage of this vulnerability, it is worrying that private information is stored in clear text. The rich data collected on users could also make carriers targets for government surveillance requests, the organization warns.

Check if you’re tracked

You can use Access Now’s tool to check if your mobile carrier deploys tracking headers at amibeingtracked.com.

Opting out

Because these trackers are injected at the network level, there’s no way for users to block supercookies.

As part of Verizon’s settlement with the FCC, the carrier will need to get customers’ permission to share its tracking data with third parties, but users still have to manually opt out. Verizon users can do so by going into the settings page.