In a US suburb famous for its battle with neo-Nazis, Donald Trump brings back unwelcome memories

Skokie, Illinois

Skokie, Illinois

“Happy anti-Trump day,” was the greeting at a bar-and-pizza joint in Skokie, Illinois this week, ahead of the state’s presidential primaries.

People don’t like the billionaire Republican frontrunner in this diverse, predominantly Democratic Chicago suburb. Asking voters about him triggered many choice words and gestures (“ass” and “waste of space” were two of the gentler ones), but the most powerful disavowal of Trump came from a Holocaust survivor who came out of Skokie Village Hall, where many residents turned out to vote.

“He’s incredibly dangerous. I lived through World War II,” said Vera, who did not want me to print her surname. “If you tell people that your life will get better if you got rid of a group of people, you know what it leads to? Numbers on people’s arms.”

Vera came to the United States from Hungary in 1956, and emphasized how easy it was for her to get a green card as a refugee at the time.

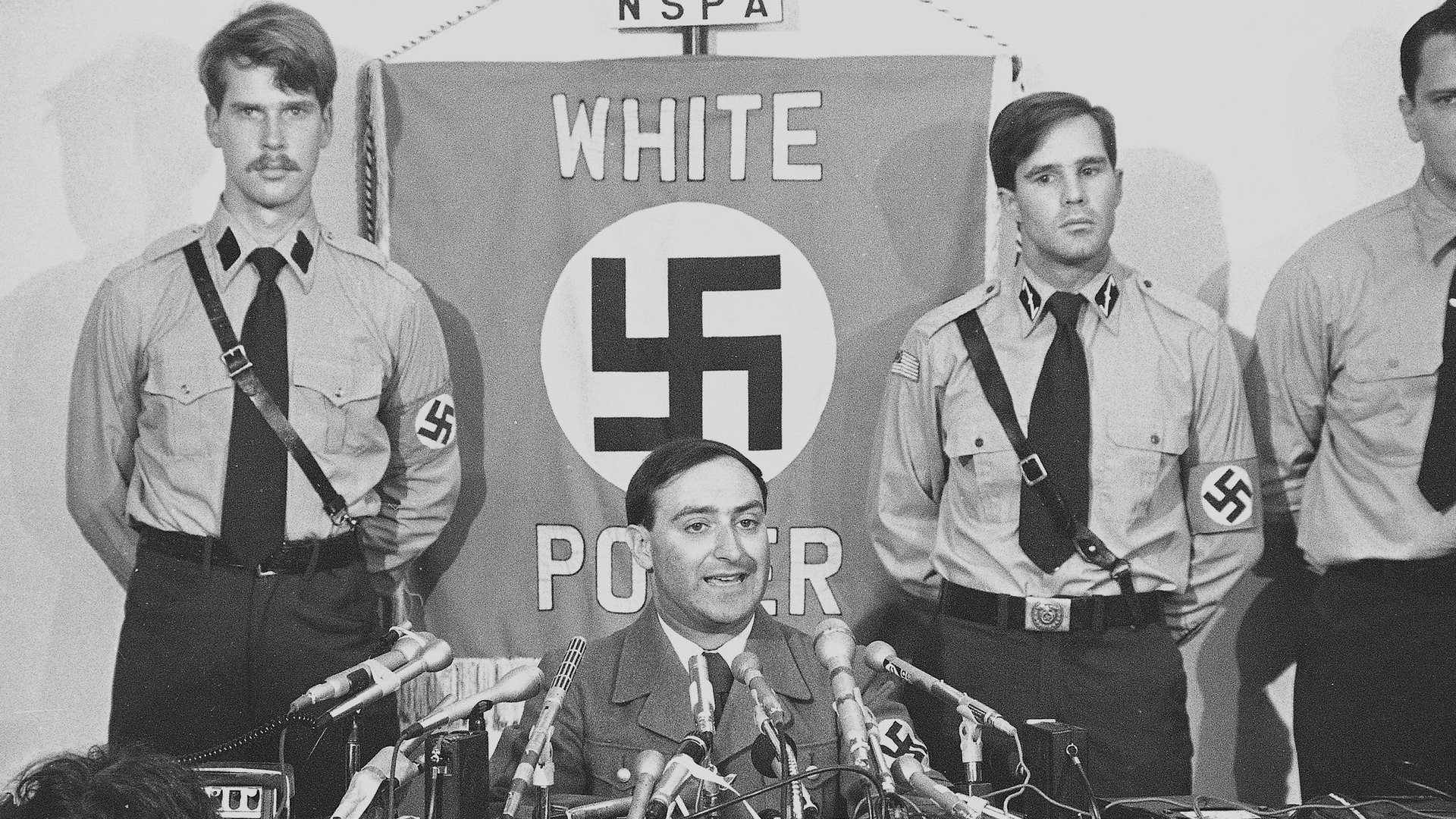

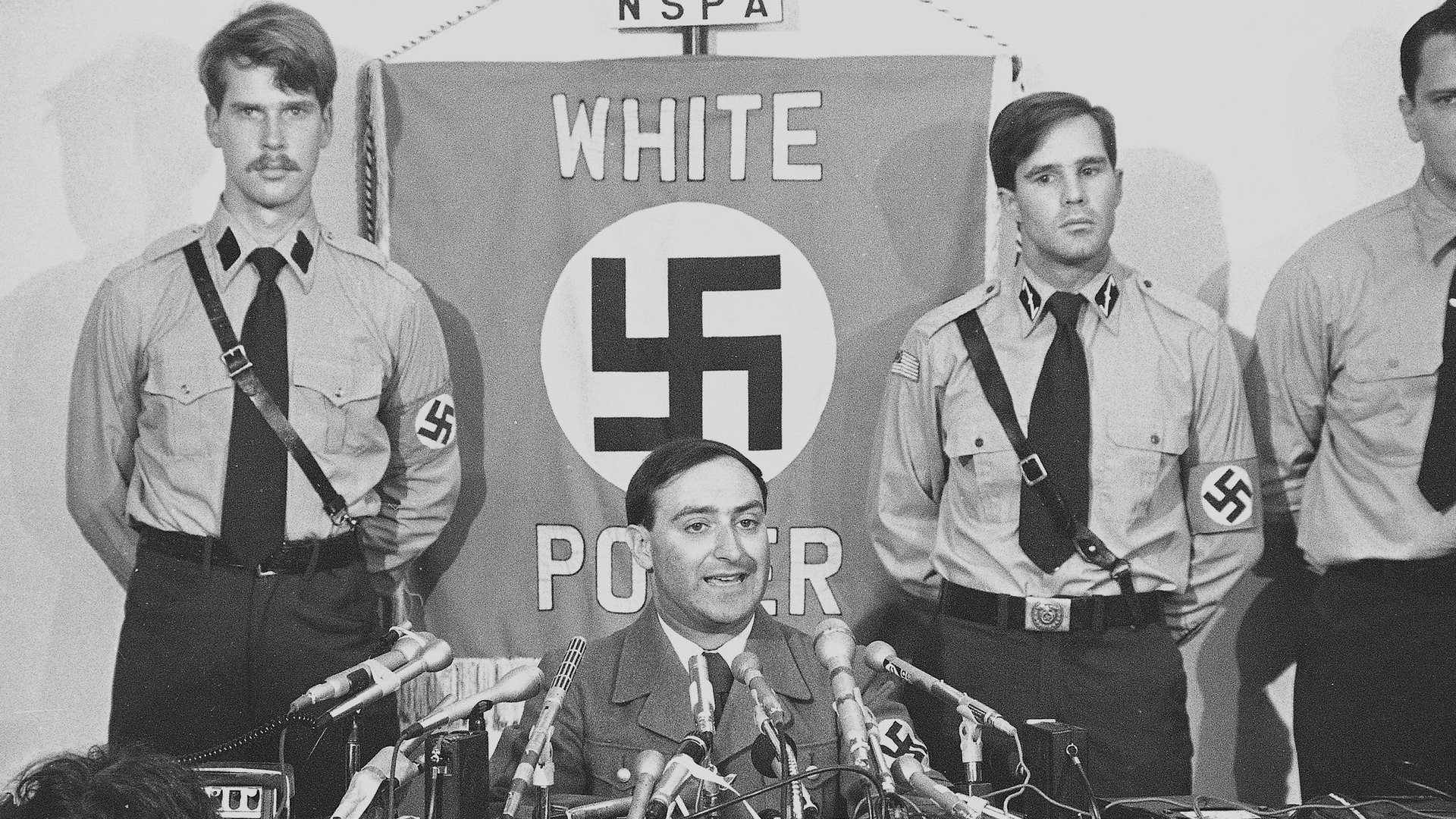

Skokie, officially a village, is famous for a failed 1977 march by the National Socialist Party of America (NSPA), more commonly known as the neo-Nazis. Leader Frank Collin and his followers planned to march through the predominantly Jewish town, which became home to as many as 8,000 Holocaust survivors after World War II.

When local authorities tried to stop the march, the NSPA sued them, and the case went all the way to the US Supreme Court, where it became a landmark decision on freedom of speech and assembly. The neo-Nazis were given permission to hold their march in Skokie, but the group ultimately called it off. (The neo-Nazis, and a town like Skokie, made it into “The Blues Brothers”).

Alan Kraus, who is in his sixties and was away from home at the time, remembers asking his father about the events that took place. “If they try to step one foot in here, I will be standing with a baseball bat,” his dad told him.

Decades later, Kraus had this to say about Trump’s increasingly violent rallies and inflammatory rhetoric: “It raises too many memories of what could happen.”

Hope Saidel, another life-long Skokie resident, said that the behavior of people who go to Trump gatherings is not unlike that of the “brown shirts,” the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party. And “Trump is much more dangerous than Frank Collin,” said Saidel, who covered the 1977 march as a reporter for a local paper.

Trump has been frequently compared to strongman politicians that exploit on racial hatred. His lackluster disavowal of the Ku Klux Klan, and a bizarre linking of Jewish philanthropists to the KKK has been criticized by Jewish leaders, and the image of a crowd of supporters raising their hands in a pledge to the candidate reminded many of the Nazi “sieg heil” gesture. Holocaust survivors including Anne Frank’s stepsister have compared Trump to Hitler.

“He’s crazy! He acts like a fool! Everybody was an immigrant,” said Bernice Oliff , whose husband was a Holocaust survivor.

Sandy Reed’s 87-year-old aunt is also a survivor. “It just makes me so angry,” Reed said, clenching her fists. “He bullies people into his way of thinking. That’s exactly what Hitler and Mussolini did.”