Photos: Dogs lead their humans through the Arctic in Europe’s most epic sled race

The horizon line in Finnmark, Norway, is invisible when it snows. A pale grey haze extends in all directions, obscuring the difference between land and sky.

The horizon line in Finnmark, Norway, is invisible when it snows. A pale grey haze extends in all directions, obscuring the difference between land and sky.

Those who choose to traverse this void cannot predict how long it will be until they eat or sleep once they set off on the trail. Many fail to complete the journey. Yet every year at the beginning of March, approximately 50 people come from all over Europe to test their limits against this Arctic landscape, their only company a team of highly-trained racing dogs.

The event is the Finnmarkslopet dog sled race, which is held in the part of Norway that lies inside the Arctic Circle. The 650 mile (1,050 km) race, is the longest dog sledding race in Europe. Only the 1000 mile (1,609 km) Iditarod in Alaska is longer.

The Finnmarkslopet race started in the early 1980s, a decade after the sport was popularized in America, as a way for European mushers to test their dogs before taking them half-way across the world to run the Iditarod in Alaska. Today, it’s both a testing ground for Iditarod hopefuls and a once-in-a-lifetime experience for hobbyists.

Stefan Falter, a 48-year-old German musher, is the latter. He learned how to mush as a child from his father and has spent most of his life around dogs, running a dog sled tour business.

This year, Falter tells Quartz that a generous offer from a private donor allowed him to enter his team in Finnmarkslopet. He estimates the cost of the entry fee and feeding his dogs for the duration of the race comes to over 3,000 euros (about $3350). He has rejected sponsorship offers in the past. “I don’t want to turn my best friends into a business,” he tells Quartz.

Mushing is a life-long hobby and career. Spending a half decade training and racing isn’t uncommon, and most mushers live with their dogs year-round. It is also prohibitively expensive—most competitive mushers have full time jobs in addition to raising and training their dogs.

Stein Fjestad, a 61-year-old Norwegian musher who raced in Finnmarkslopet this year, owns one of the largest onion farms in Norway. He has 40 dogs, which he uses most of his income to sustain, about 50,000 euros per year.

Fellow Norwegian musher Petter Jahnsen, 50, is an electrician. Like Fjestad, he says he spends most of his income on his dogs. ”Mushing for me has to be an hobby,” he tells Quartz. “I don’t want to transform it into a profession, because that would spoil the fun.”

The town of Alta, where Finnmarkslopet begins and ends, bustled with excitement leading up to the race’s Mar. 5 start date, this year. “There are among two and three thousand spectators when we start in the hometown of Alta,” Trond Anton Andersen, the director of Finnmarkslopet, tells Quartz.

Once the mushers leave Alta, they are alone. Their only contact with civilization comes at check points located roughly every 50 kilometers of the loop that forms the 1,050 kilometer race.

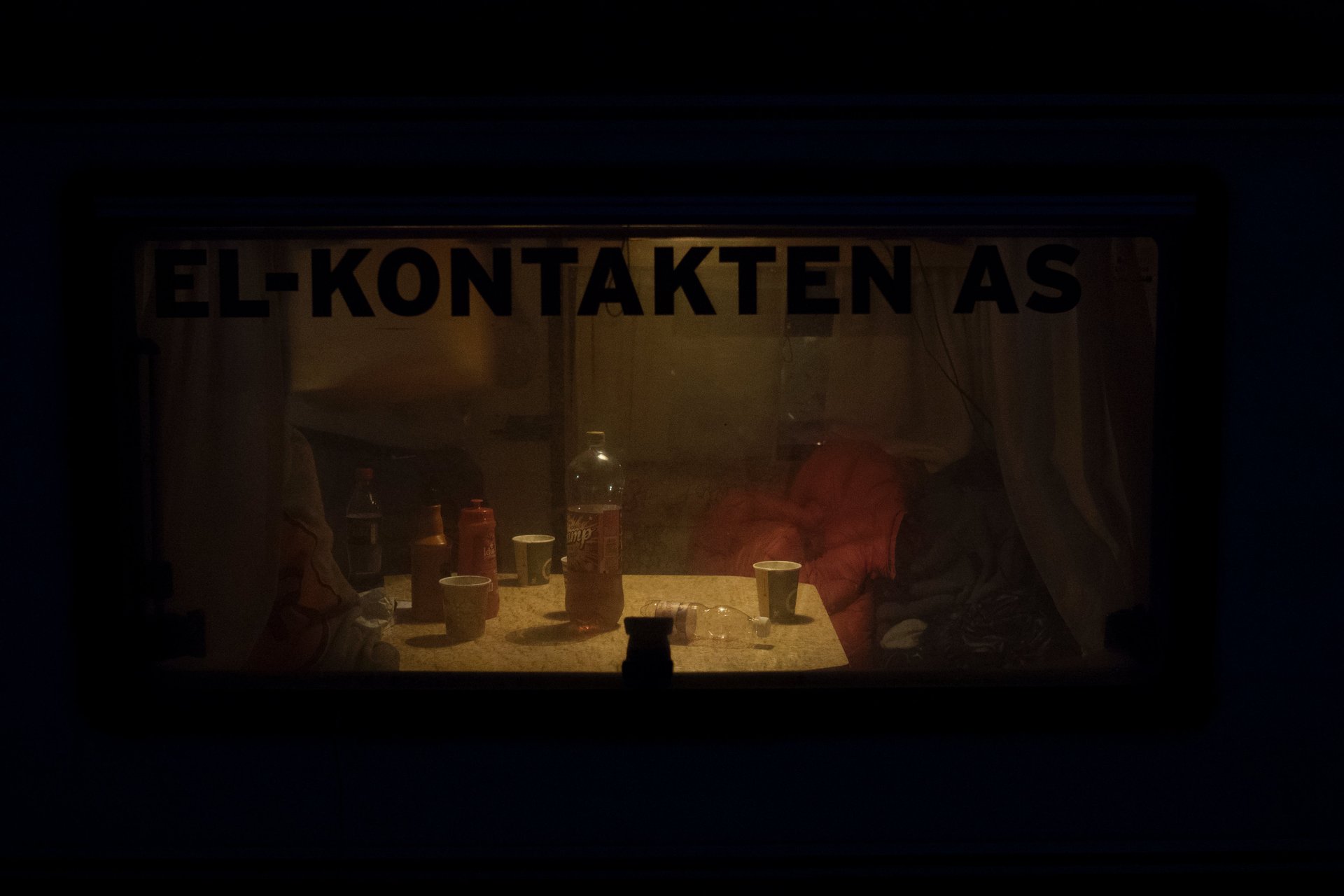

At the second check point, in Skoganvarre, the racers are required to stop to eat and sleep. They arrive late at night, on the first day of the race.

Mushers allow their dogs to rest at the midway check points during the day. When they stop, the first thing the musher does is unleash the dogs and feed them. Then, the musher covers them in order to keep them warm while they sleep.

Lodgings for humans at each checkpoint ranges from heated cabins to yurts lined with reindeer skins. Mushers and their assistants get three hours of sleep each night, on average.

Crowds gather in Kirkenes, Norway, at the halfway point of the race. A concert is held there to celebrate the mushers as they pass through the checkpoint and enter the second leg of the race.

The second leg is harder than the first, as the dogs begin to tire out. Each musher begins with 14 dogs, but can continue to race with as few as six dogs.

Stefan Falter was forced to drop out at the first checkpoint in the second half of the race, in Neiden, Norway, when his two lead dogs gave out. Without them, his team fell apart.

Crowds gather in Alta to welcome the mushers back as they cross the finish line. The first three mushers crossed the finish line on the seventh day this year, while the last of the mushers took eight days to finish. Twenty-eight teams finished the race, while 14 dropped out.

This year’s winner was the Swedish musher Petter Karlsson. A Norwegian woman named Marit Beate Kasin from Norway took second, and another Norwegian musher, Arnt Ola Skjerve, took third.

Despite failing to finish the race, Falter says the experience changed his mind about racing, and that he will seek sponsorship to continue to race in the future.