Inside the studio of the “micro-engraver” who works between heartbeats to keep his hand steady

Birmingham, UK

Birmingham, UK

In 2012 an Indian artist from Assam called Sujit Das created a minute carving of the Hindu goddess Durga. He was certain his effort, which measured just one inch, couldn’t be bettered, and announced as much.

Graham Short, a British micro-engraver, accepted the challenge. His Durga image is a mere millimeter across.

This is far from a one-off. Short’s most recent work—and his favourite—is a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, completed in time to commemorate her 90th birthday on April 21. It is carved onto a speck of gold stuffed into the eye of a needle.

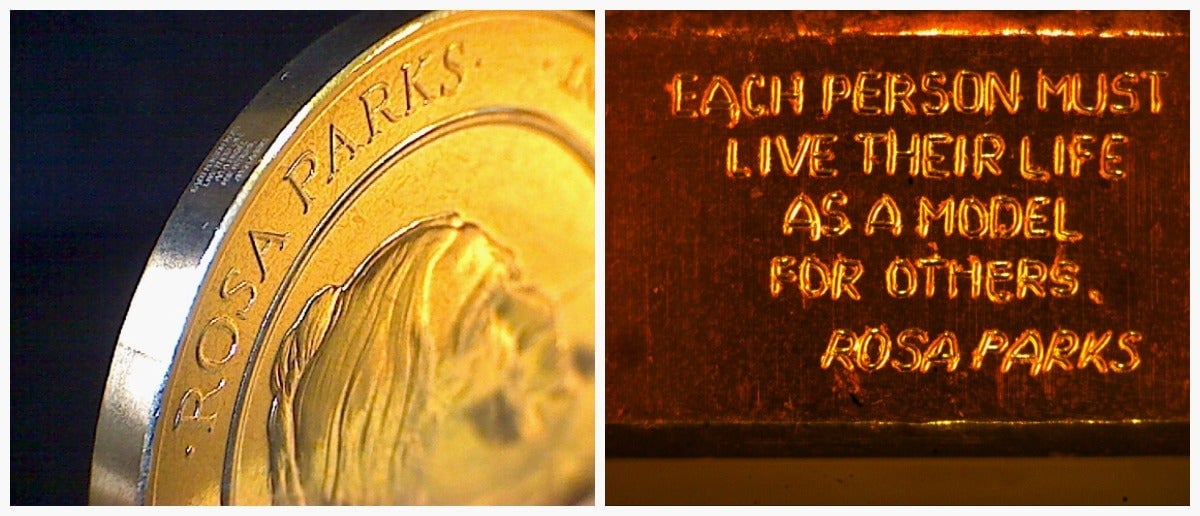

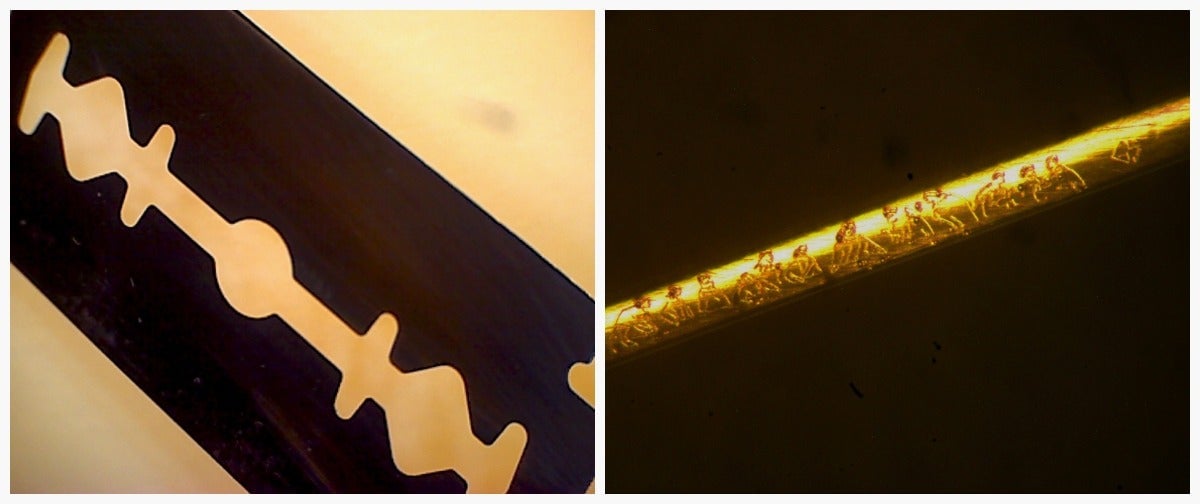

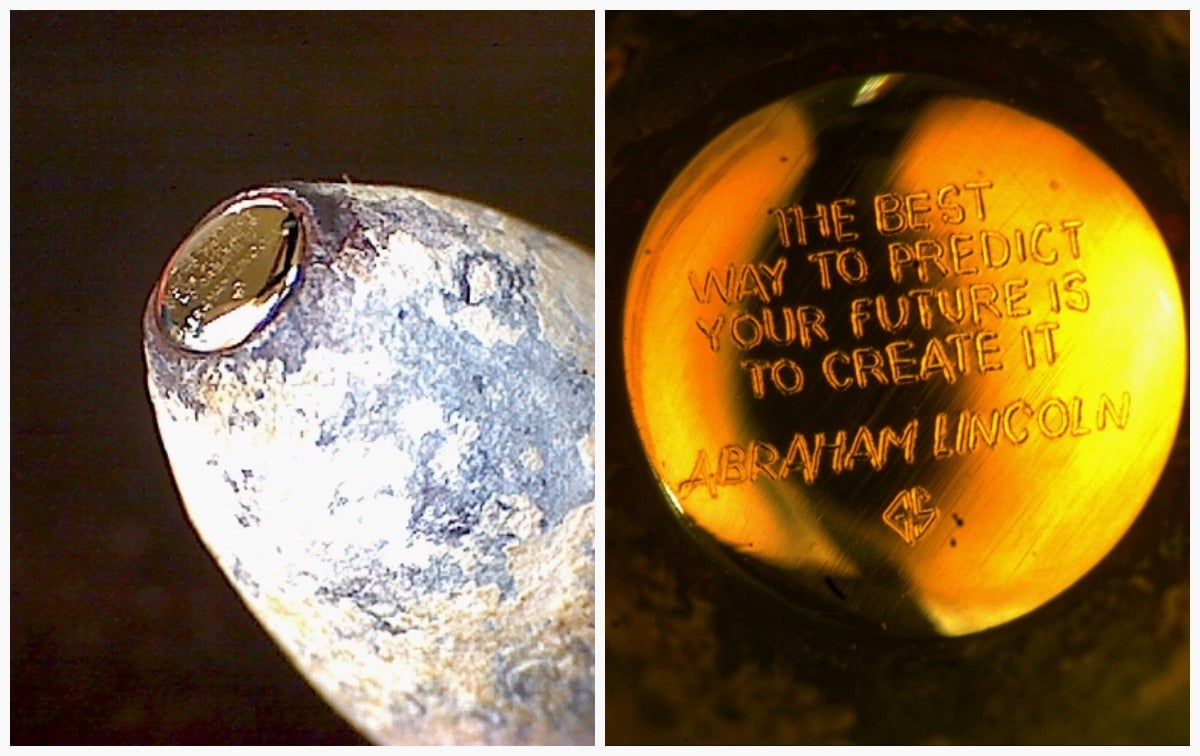

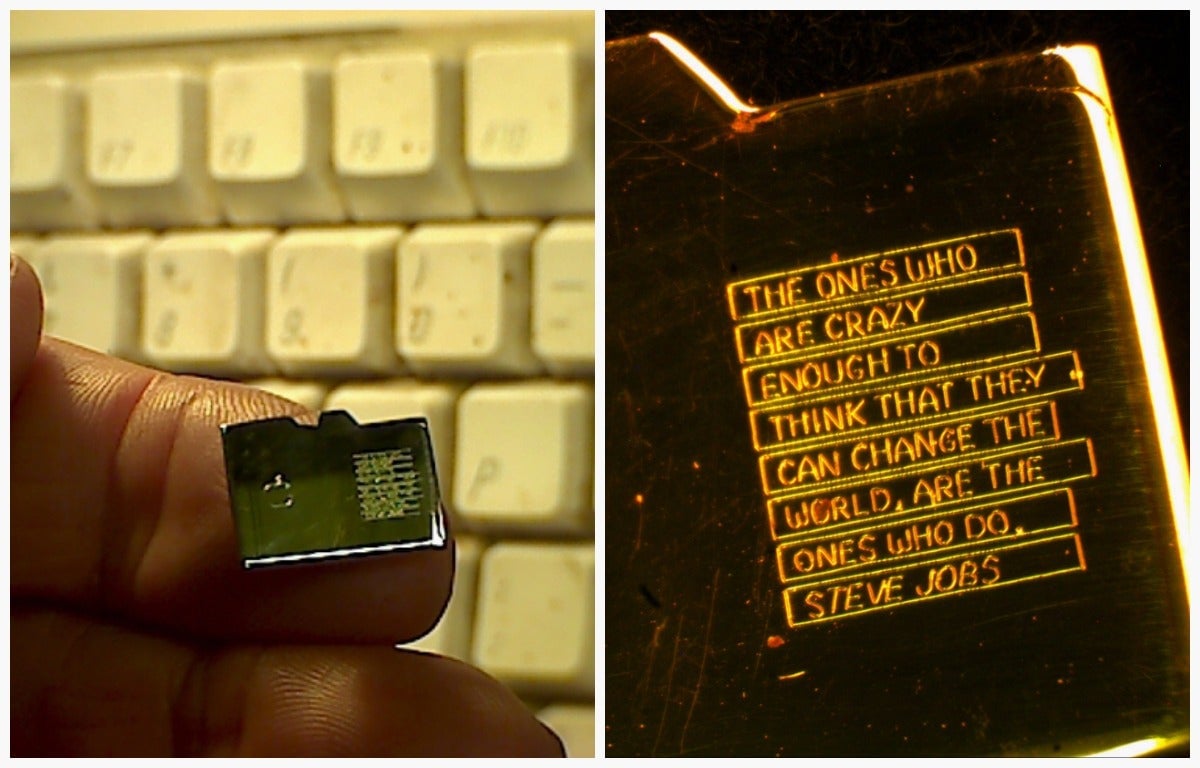

Based in a tiny studio in the jewelry quarter in Birmingham, Short has also inscribed a quote from Abraham Lincoln on the tip of a Civil War bullet, one from Rosa Parks on the rim of a commemorative medal, and one from Steve Jobs on a gold microchip the size of a fingertip. The piece that gave him the most battle scars are the words “Nothing is Impossible”, which he scratched along the business edge of a razorblade. He used another razor edge as a canvas for a depiction of The Last Supper.

“I can do something,” Short says, “that no one else on a planet of 7 billion people can.” But it seems this is not enough. He is always looking for new challenges. New quotes. New tiny canvases on which carve, just to show he can: pen nibs, pinheads, even—once—the pointed end of a paperclip. The quotes, at least, are easy to find: “They all say a lot, these famous people.”

Although the end result is so small, Short’s technique, honed over a lifetime, is physically grueling. Silence is essential. Taped to the wall of his studio is a sign reminding him to switch off his mobile phone. To avoid the vibrations of passing lorries, he works only at night, sitting down at his bench at midnight and downing tools at five or six in the morning. He can work like this for three or perhaps four nights in a row before he gets too tired and needs to let his body clock readjust.

Apart from quietude, Short’s most essential tool is his own body. First, to steady himself, he ties one end of a strap around a heavy piece of machinery in his studio. He secures the other around his right arm, pulling it taut. He tapes a stethoscope to his chest and places the earpieces in his ears. He holds the carving tool—a needle pushed into a wooden engravers’ handle—in his right hand like a pen, and peers through the eyepiece of the microscope.

He may wait like this, motionless, for 20 minutes or more before making an incision. Finally, listening through the stethoscope, he carves when he is at his stillest—in between heartbeats.

He is lucky that he has always been fit and slim and healthy, something he puts down to his lifelong love of swimming. Fourteen years ago, when he was 55, he became the European butterfly champion in his age group. To keep his heart rate down, he now swims for three hours each day—5,000m (3.1 miles) each morning and a further 5,000 each afternoon. He stopped drinking coffee on work days years ago.

But although the swimming helps slow his heart significantly, it is no longer enough. Several years ago a pharmacist friend began prescribing him pills—potassium, magnesium and beta-blockers. “I eat them like sweets,” he admits. When he works, his heart rate drops to as low as 20 beats per minute.

Another problem: Nearly 10 years ago he found himself blinking more and more rapidly, because peering through the microscope for long periods strained his eyes. Now he has botox injections around his eyes every few weeks to hold the muscles in place. Sometimes, when his eyeballs become too dry, he has to move his eyelids over them by hand.

Because binding his arm and holding it in readiness for long periods is so painful, and the carving so delicate, Short works in fits and starts. He sits peacefully for hours, listens to his heartbeat, and lets his mind roam. Sometimes he remembers the shame of wearing handmade clothes to school; or the sweet, chemical smell of silver polish from the house where his mother worked; or the esoteric flight patterns of the tumbler pigeons his neighbor bred. Sometimes he wonders whether, if he dies in his studio one night, people will know exactly when he died, which cut was his last.

In the moments between resting and waiting, he carves. When working on the smallest, most difficult pieces, he will manage only six or seven cuts in a night, just enough to complete a letter “E”. A single work, depending on its size and level of complexity—the Queen’s hair was, apparently, particularly challenging—will take between three and nine months.

He has learned not to hurry, though, because mistakes are costly. The needle point, sharpened to the point of invisibility on a whetstone, need barely touch the surface of the carving to make a mark. When he slips—and, of course, he slips often—the work will be ruined: He must polish the surface and begin again. Once, when he had finished working on a minuscule tribute to NASA, he noticed that he had missed out a letter “I”. Annoyed, he bent down to correct the error. The needle skipped, obliterating three months’ work.

The frequency of such mistakes is the reason his preferred medium is a gold pin; it takes no time at all to buff one back to smoothness. However, a big slip, particularly one on a near-completed project, is so demoralizing he finds he can’t bear to start from scratch right away. He works on three or four pieces simultaneously, picking them up alternately after they suffer a mishap.

But slips are not the only sort of disaster to befall him. More than once he has dropped completed works as he removes them from the microscope, but they are so small he has been unable to find them again on the greasy carpet of his studio.

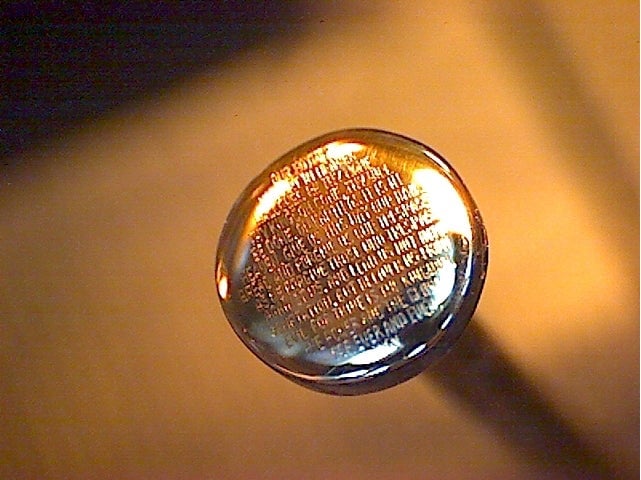

Engraving the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin was a project that was to consume him, on and off, for nearly half a century.

When Short left school at the age of 15, he hadn’t a single qualification to his name. One of the few options available to him was to become an apprentice, so the very next day he signed on at a nearby stationery engraver’s. Initially, he loathed the work. The workroom was old and dirty; it smelt of hot machinery, oil, and the dye used on the presses. As the youngest and most junior member of the team, Short began each day by disposing of the mice caught in the traps he had set up the night before.

Soon enough he discovered he had a natural talent for engraving. He spent his career creating stationery for banks, royal palaces, and perfume companies.

But it was during his time as an apprentice that he developed his taste for the miniature, when the head of the workshop challenged the trainees to create an etching of the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin. Embarrassed by his failure at school, and desperate to stop having to empty the mousetraps, Short was determined to prove himself. While the other boys were playing football over the lunch break and in the evenings, he worked on version after version of the prayer on ever-smaller scales.

His first breakthrough came when he discovered that placing one magnifying glass over another allowed him to see more detail. Later, he abandoned regular steel dressmakers’ pins—which were brittle and couldn’t be re-used—for more malleable gold ones made for him by his jeweler neighbors. He also had to get better at planning the design. “I had no idea of spacing at the beginning. I’d reach the end of the pin and be half way through a word. Or I’d be near the bottom but have another four lines to go.”

In 2010, more than 40 years after his first attempt, he at last succeeded. “I couldn’t stop looking at it. I had taken up most of my life trying to get that done.” Naturally, he immediately wanted to show the world. He had a special case made with a built-in magnifying glass and lighting system, and sent images to galleries and newspapers.

Short describes himself as an extrovert and, on the day we meet, he looks the part, wearing a linen jacket decorated with a blue patchwork Union Jack, black-and-white-spotted mock-croc lace-ups, and faded Wranglers. He is friendly and voluble, talking in a faintly nasal Birmingham accent about previous projects, well-known people he’s worked for, and how he met his wife (buying an ice cream while on holiday in St Petersburg, since you ask).

Above all, Short is desperate for people to know what he is doing, and is increasingly frustrated by the lack of recognition. “I want people to realize, more than anything, how difficult it is.”

During his lifetime, the dominant trend in the art world has been for larger-scale work. Beginning in the 1960s, American artists such as Robert Smithson began using industrial equipment to make artworks that used the landscape as their canvas, and the popularity of site-specific, immersive, and installation art has only increased since. This is reflected in art prizes and exhibitions: “The Probable Trust Registry” by Adrian Piper, which won the 2015 Venice Biennale Golden Lion, was an immersive, interactive office space complete with three staffed desks.Last year’s Turner Prize went to an architecture studio and design collective for their work regenerating an estate in Liverpool. The Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern in London has drawn over 60 million visitors since 2000 to its gargantuan installations, including Ai Weiwei’s “Sunflower Seeds”, which filled the 500-foot long space with over 100 million hand-painted porcelain seeds the size of a pinkie fingernail.

Short’s work, by contrast, is practically invisible to the naked eye. Held in the hand, the engravings are no bigger than scratches, like those around a keyhole. They can be photographed, of course, but even this is difficult without highly specialist equipment.

And by themselves the final images give little indication of scale. When he completed his first work on the edge of a razor blade—the “Nothing is Impossible” piece—he contacted the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers, hoping to exhibit in their annual show in central London. When he told them about more about the piece, with its custom display case, they were apparently reluctant. “Can’t you engrave it a little bigger,” he was asked, “so that we don’t need a microscope?”

For Short, however, the size is only half the point. As his efforts to miniaturize become increasingly baroque, it becomes ever more difficult for someone else to better him, as he bettered Sujit Das. “They won’t be able to do it,” Short says. “They won’t go to these lengths. And I don’t blame them either.”