Research says children are smart enough to know when they’re being treated like they’re stupid

Jayden wasn’t getting on with his math work. “Can I help you Jayden?” I asked. “I can’t do this work, Miss, I’m only a moped.”

Jayden wasn’t getting on with his math work. “Can I help you Jayden?” I asked. “I can’t do this work, Miss, I’m only a moped.”

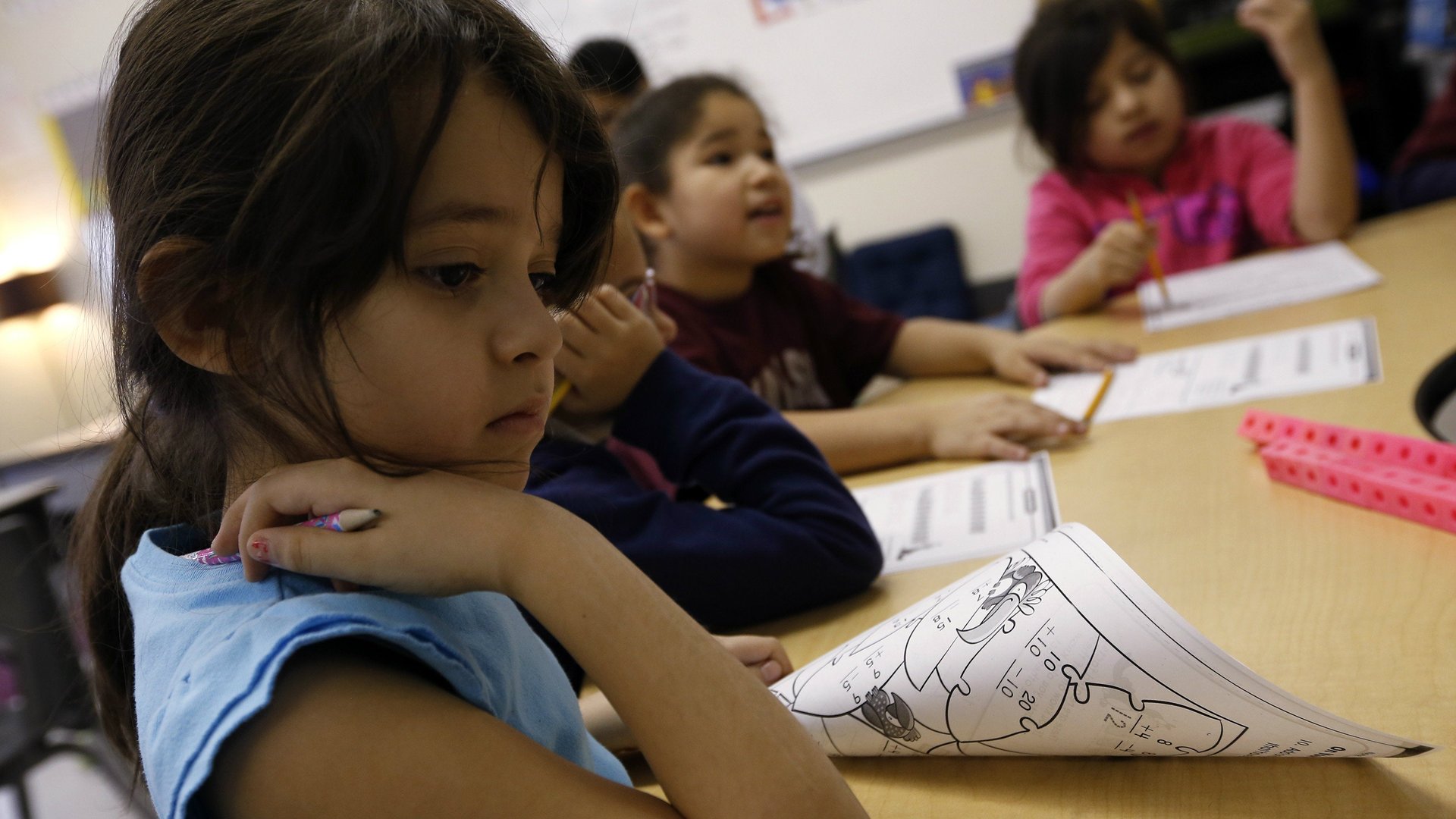

Jayden was six years old. Like many primary schools across the country, Jayden’s separates children into different groups according to their ability—in his case, named after different vehicles.

Jayden knew he was a moped and not a Ferrari, and had made a link between being a moped and not being good at math. Whether groups are labelled by vehicles or animals, colors or shapes, children and their parents understand the implied meanings.

As ability-grouping becomes increasingly common in primary schools, my recently-published research looked at the experiences and feelings of the young children affected.

While teachers, children, and parents often concern themselves with the level of the tasks assigned to each group, I found that group labels do more than this—they say something to and about the children in the groups, too.

Ferraris and mopeds

Grouping children by ability seems like a reasonable response to government directives that schools address the needs of every child. It also fits nicely with the idea in English society that being “good” at something, or having a “talent”—be it sport, music, or math—is more about having the right genes than putting in effort, and that we can assess and group by “ability.”

But we now know that genes do not dictate destinies. We also know that while being in a top stream may benefit some children, ability-grouping is not a panacea to raising attainment. It may also have detrimental effects on children’s attitudes toward a subject.

There are other problems, too. Teacher stereotypes, the month of birth, social background, and special educational needs all impact which group a child might be placed in, and therefore the educational opportunities afforded to them.

Despite a wealth of research arguing against the use of ability-grouping, this has little impact in schools. Primary school children, sometimes from the age of four, are increasingly experiencing structured forms of ability grouping.

Children understand

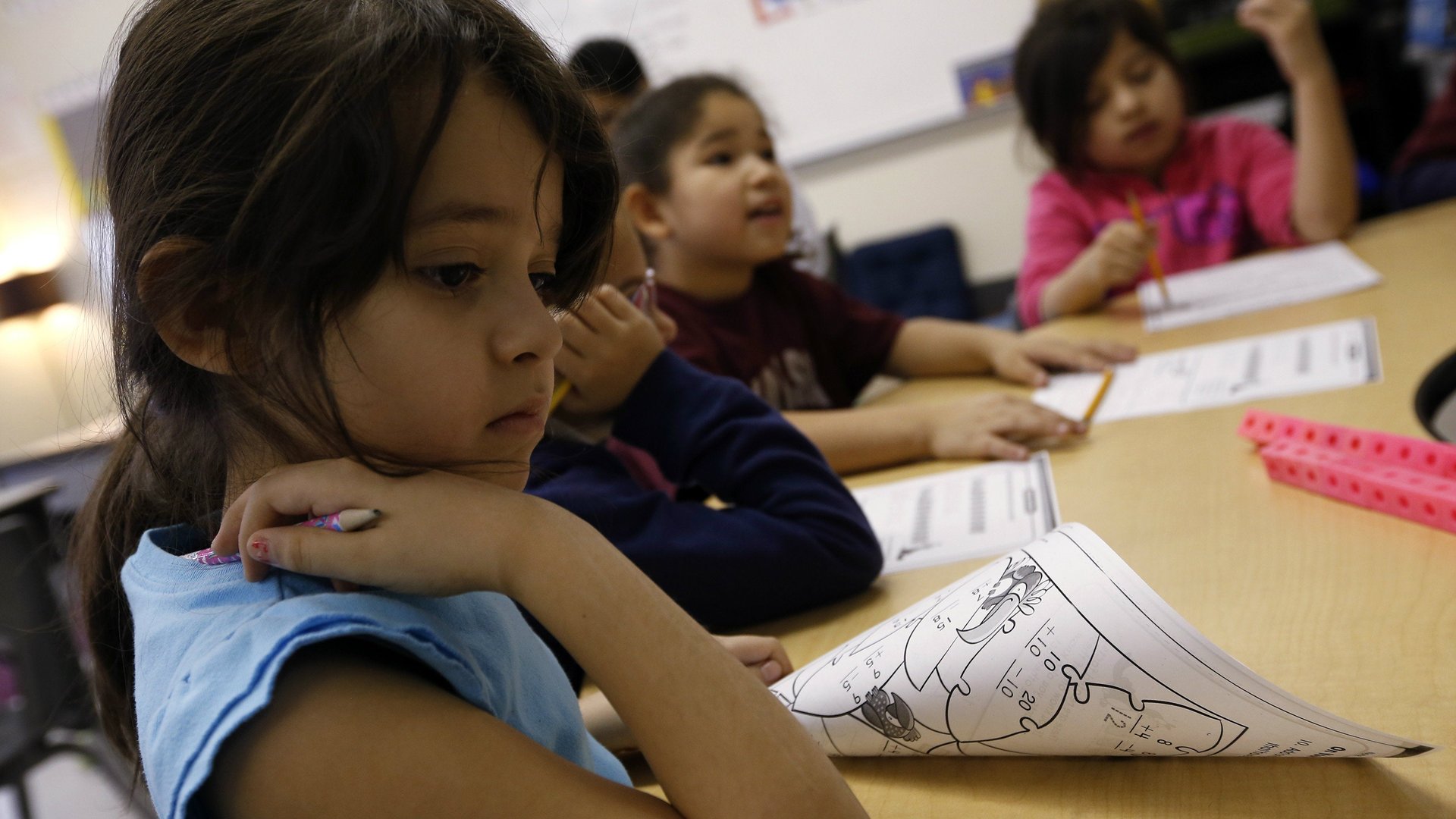

Children know what their placement means. Eight year-old Louise, sat on the bottom table, told me: “It makes you know you’re worst at maths.”

These views were not uncommon among the 24 primary-aged children I interviewed from both top and bottom groups, who all study math as part of the national curriculum. Over 70% had fixed mindsets, believing that math ability was determined at birth.

Nine-year-old Yolanda, who was in a bottom group, explained why some children were good at math: “Their brain’s bigger … it just happens. They were born like that. They were born clever.”

Children bought into the ability labels they were given, but also felt constrained by them. Despite being in a top group, Peter, who was about to embark on secondary school, adamantly stated that his improvement could only be minimal because: “There’s only so much you can do, isn’t there?”

Labeling or grouping children by ability appears to place real limits on the willingness of many to “have a go.” Many children in my study also saw their ability as fixed not just now, but in the future, too. As Samuel, also at the end of primary school, reported angrily: “I’ve always been last in every maths group … I’ll just be low now in my next school, too.”

Sadly, Samuel’s assertion may well be true. Ability-driven group placements appear to persist into adulthood. The mopeds may always be the mopeds.

Splitting up friends

In some schools, young children are expected to move to classes of different ability levels (and so to different classrooms with different teachers) for different lessons—essentially a secondary school practice brought into the primary environment. But this can simply be too much for a young child whose main concern may only be who they’re going to play with at lunchtime. Being in different classes, children have to manage a greater range of friendship groups.

As Louise told me: “You know in the groups? It takes you away from your friends.” This is important. By breaking up friendship groups, teachers may actually limit the possibility of collaborative work. Ability-grouping also takes young children away from the pastoral support of their class teacher.

Many children rely on school to provide nurturing and consistency. Traditionally, the primary school teacher develops a holistic understanding of their class, knowing how well each student is doing, what motivates them, and recognizing their fears, interests, aspirations, and home background. Teaching children in ability-based sets and streams may make this harder.

The increase in ability-grouping in primary schools brings with it many different experiences for young children. Grouping children by ability affects how children feel about themselves, both now and in the future. I believe these are not the experiences and feelings we want such young children to have.