Facebook has a lesson to learn from Nintendo’s massive 1990s virtual reality failure

On Monday, Mar. 28, Facebook’s Oculus started shipping its first virtual reality headset to consumers. But it may have a hard time convincing US users to try it out: The last time a large multinational company tried to bring virtual reality gaming to the world was 21 years ago, and it was a categorical failure.

On Monday, Mar. 28, Facebook’s Oculus started shipping its first virtual reality headset to consumers. But it may have a hard time convincing US users to try it out: The last time a large multinational company tried to bring virtual reality gaming to the world was 21 years ago, and it was a categorical failure.

In the 1990s, Nintendo’s Virtual Boy console promised gaming in virtual reality, and failed to deliver on just about every count. Nintendo wasn’t immediately available to confirm to Quartz how many Virtual Boy consoles it sold since launching in 1995, but reports suggest that fewer than 800,000 of the nausea-inducing units shipped before being taken off the market. The consoles before and after it, the Super Nintendo and the Nintendo 64, both sold about 30 times better, according to Nintendo.

Back then, Nintendo was as much a household name as Facebook is today. The company stuck to its core area of expertise—videogames—but its characters appeared in movies, TV shows, cartoons, and just about every piece of clothing and merchandise imaginable. After revitalizing the videogame market with its 1985 Nintendo Entertainment System, Nintendo followed up with two more smash hits: the Game Boy and the Super Nintendo. The next step, some believed, was to translate the gaming company’s success to a new medium.

“What should be done to once again engross Famicom and Super Famicom [the Japanese term for the NES and SNES] players?” Gunpei Yokoi, the creator of the Game Boy, wrote in his 1997 book, Gunpei Yokoi Game Pavilion.”If the TV screen medium has reached the limits of its potential, isn’t 3D the only option?”

Then came the Virtual Boy.

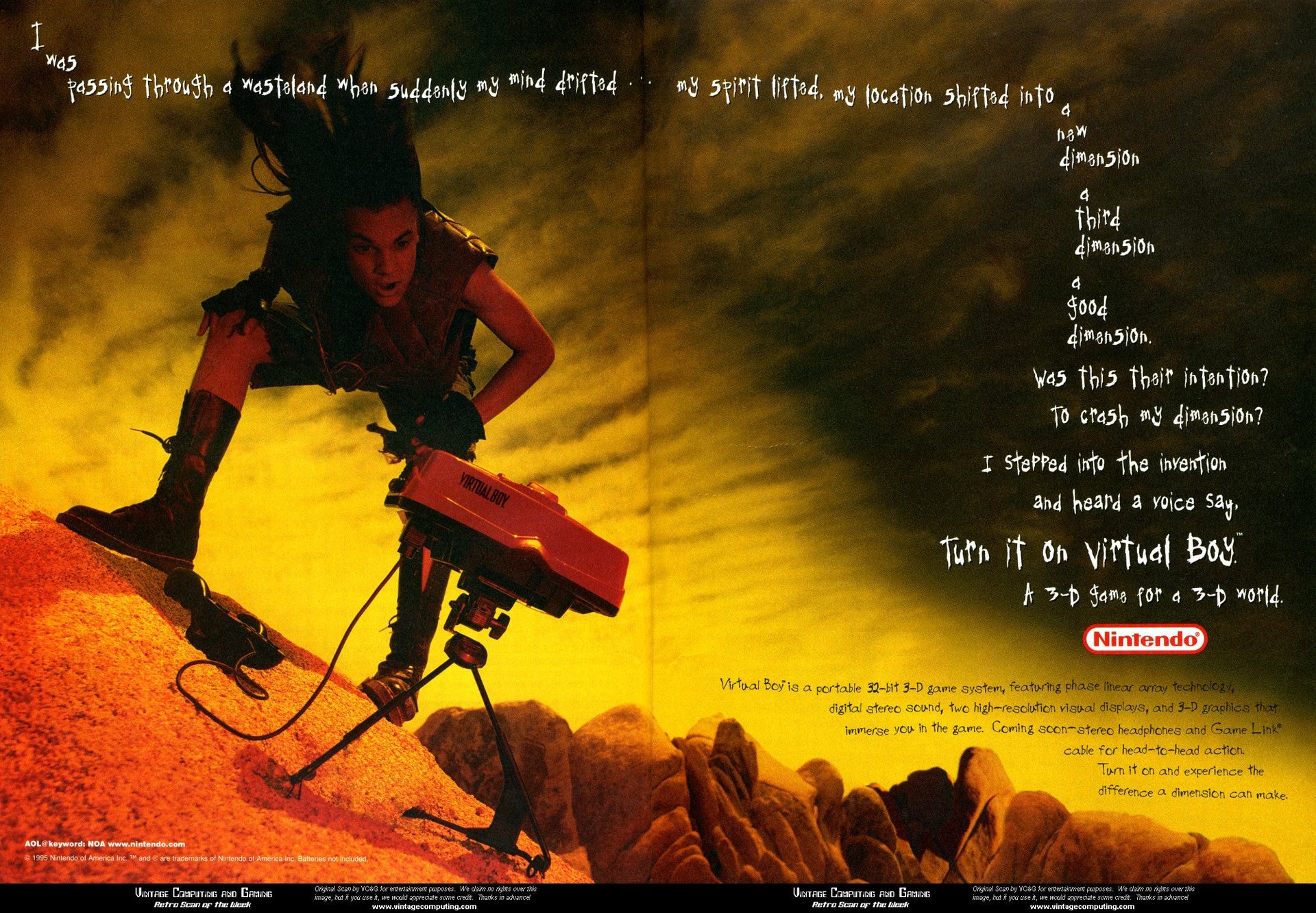

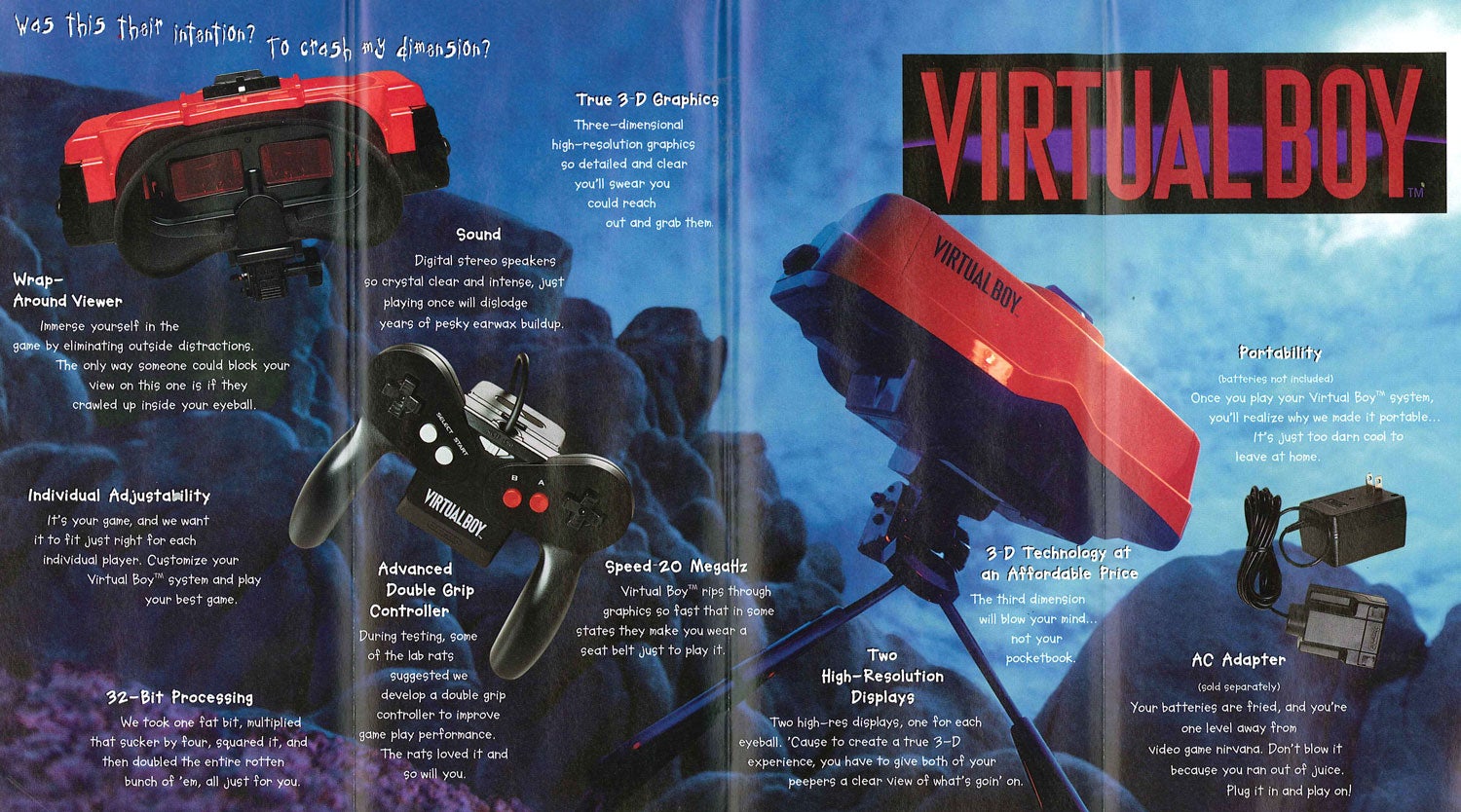

Nintendo marketed the new 3D gaming system in a typically ’90s cyberpunk style, aimed at young gamers.

The system was priced $180—a little less than Nintendo’s 2D home consoles, and about double the launch price of the Game Boy.

The Virtual Boy was even hyped on the cover of Nintendo Power, the company’s gaming magazine, with a 1990s circulation of around 2 million.

But the Virtual Boy failed to take off. One problem was that, even though it shared the “Boy” naming convention of the portable Game Boy, it wasn’t really portable. The console sat on little legs, meaning you needed a table and chair to play with it. Even then, it sat at an awkward height that wasn’t really adjustable.

The games weren’t really in virtual reality, either. They were essentially red lines stacked on top of each other, seen through a viewfinder. Unsurprisingly, playing the Virtual Boy tended to cause motion sickness and headaches.

Nintendo executives have joked that the Virtual Boy project traumatized them. A year after it was released, you could pick up a system at the cut-rate of $30, and games for $10, Wired reported.

In a Jan. 2016 question-and-answer session on Reddit, Oculus founder Palmer Luckey said that he didn’t consider the Virtual Boy a true VR device, and that it may have created a negative public perception of virtual reality: “A real shame, too, because the association of the Virtual Boy with VR hurt the industry in the long run.”

Will 2016 end up looking like 1995? Probably only if you’re watching the movie Dope. Today’s virtual reality systems like Oculus, HTC’s Vive and Sony’s PlayStation VR are a world away from Nintendo’s rudimentary 1990s console. Virtual reality technology has improved massively in the last two decades, and the VR content being published feels impressive, immersive, and—most importantly—fun. But there’s still a high barrier to entry right now: VR systems require thousand-dollar machines, and the headsets themselves cost upwards of $500.

Although initial reviews of the Oculus Rift seem tentatively positive, Facebook and others branching into VR need to show everyone that they are selling something worth buying, that won’t make them sick and is worth jamming their heads into a weird box for hours. And until the average person can walk into a store and actually try out a VR headset, that’s a hard sell.

Earlier today, Facebook and Oculus CEOs Mark Zuckerberg and Brendan Iribe hosted a live video walking through the Rift and what’s in store for the year. Zuckerberg said that Facebook intends to be involved in this project ”for the long term.”

They also explained that, while video games may hold your attention for a few months at a time, social connections will keep people coming back to VR. Referring to conversations he’d had with people in other places using Oculus headsets, Iribe said: “It feels like a physical memory, like you’re there in a physical space. It’s incredible.”

That’s an experience that the Virtual Boy’s red lines just couldn’t have created.

Image by Titoulechien on Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.