A surprising number of people are getting trapped for months on end in Moscow’s busiest airport

On August 18, 2015, Hasan Yasien checked in at Sheremetyevo airport for a flight to Turkey, cleared customs and passport control, and headed towards the gate to catch his plane.

On August 18, 2015, Hasan Yasien checked in at Sheremetyevo airport for a flight to Turkey, cleared customs and passport control, and headed towards the gate to catch his plane.

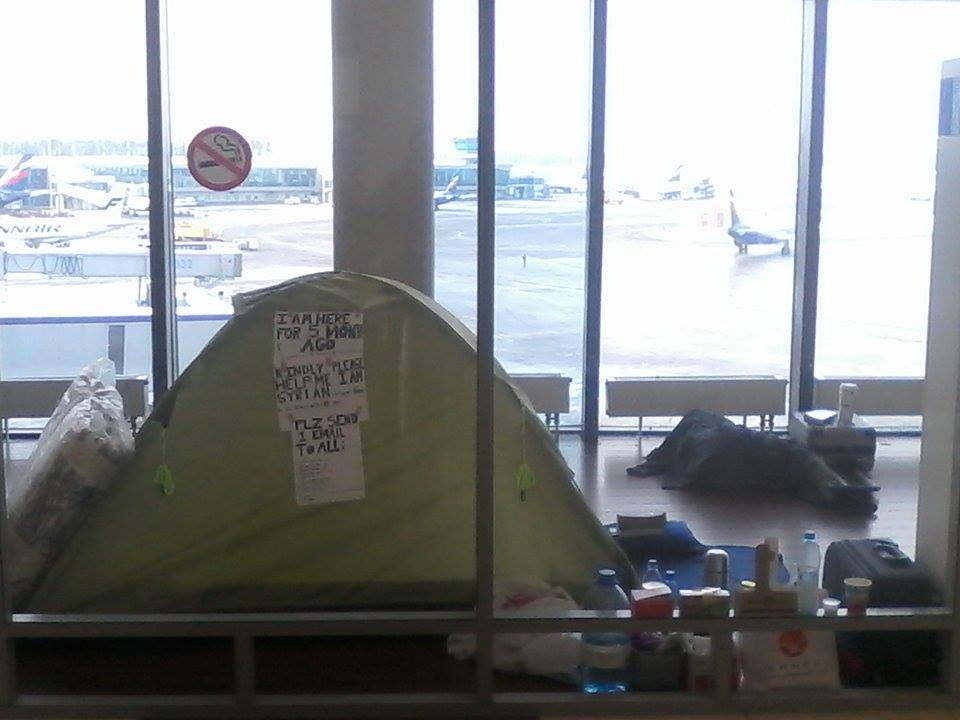

Seven months on, the 42-year-old Syrian is still there. He lives in a small green dome tent in the international departure lounge of Terminal E, surrounded by supplies provided by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the occasional friendly traveler. He maintains increasingly desperate communications with the outside world on his mobile phone.

He’s lucky there’s free Wi-Fi.

Yasien is far from the only person to have spent weeks, months or even years trapped in the international no-man’s-land of an airport lounge. The most famous was Mehran Karimi Nasseri, whose 18-year stay in Paris’s Charles De Gaulle airport was the subject of the 2004 film The Terminal, starring Tom Hanks.

But in the annals of Kafkaesque airport limbo, there may be nowhere quite like Sheremetyevo, which last year reclaimed the title of Moscow’s busiest airport. Yasien is one of at least a dozen people to have been an unwilling long-term guest there since 2013, when Edward Snowden, on the run from the US government, spent 39 days waiting for Russia to grant him asylum.

And even among these unfortunate souls, Yasien’s story is one of the stranger ones. Most of them got stuck trying to get into Russia. He has been trapped trying to get out.

“Is America fighting on your land?”

Yasien hails from Atarib, a town northwest of Aleppo. He fled the fighting there in 2012 for Lebanon, where he worked for more than two years. (A former employer there confirmed this to Quartz.) As Syrian refugees continued to flood into Lebanon and jobs became scarcer, he went to Russia in July 2014, at the invitation of another Syrian who, he said, operates a textile business in Noginsk, near Moscow.

While working in Noginsk, sharing three unheated rooms with some 20 other foreign workers, Yasien applied for asylum. In December, he was turned down. Yasien’s condition, the federal migration service said in its explanation, was no worse than that of the average Syrian; the conflict in Syria wasn’t a war but a “mass counter-terrorism operation”; and people like Yasien were trying to leave “not because they are afraid of being killed, but because the economic and humanitarian situation is getting worse.” (According to the Civic Assistance Committee, an NGO which monitors refugee rights in Russia, the claim that things in Syria just aren’t that bad is quite a common one in Russian asylum rejections.)

Yasien—by now in the country illegally—says he went back to work for the Syrian in Noginsk, and then at a workshop owned by an Azerbaijani. But by the summer of 2015, having earned just a few thousand dollars and finding himself regularly harassed by police for bribes, he had enough, and decided to leave for Turkey.

Having overstayed his visa, he obtained a court ruling, seen by Quartz, which allowed him to pay a fine of 5,000 rubles (then about $76) and leave the country within 15 days. The very next day, he was at Sheremetyevo, ticket in hand.

Why his passport was taken remains a mystery. In the departure lounge, Yasien says, a Russian border official approached him and asked why he was trying to fly to Turkey—did he not like Russia? When Yasien explained that he had failed to get asylum in Russia, the official retorted “Is America fighting on your land?” Then she demanded Yasien’s passport, saying a judge had ordered it to be confiscated.

Zalina Kornilova, the chief of the federal migration service, told Quartz the decision to confiscate it may have come from the Federal Security Service (FSB). The FSB did not respond to Quartz’s request for comment.

Between Aug. 18 and Sept. 8 Yasien tried twice more to get on flights out of the country—once to Turkey and once to Lebanon. (Quartz has seen his ticket receipts and independently verified the Lebanon ticket.) Each time, he says, the Russian authorities took his passport before boarding and gave it to the airplane crew, who handed it over to the Turkish or Lebanese border officials upon landing. Each time, the border officials told him that because the passport had not been physically in his hands when he landed, he could not enter the country, and sent him back to Russia.

He still hasn’t gotten his passport back.

“I want a solution to my problem”

Using his phone, Yasien began sending pleading emails to assorted international organizations (typical subject line: “Please… I want a solution to my problem”). Two months into his ordeal UNHCR responded. It now sends him weekly food packages and has engaged Russian lawyers to take his case to the European Court of Human Rights. The phone is his lifeline; after one of us (Schwartz) first encountered him at the airport during a layover, we did follow-up interviews over WhatsApp.

He has had quite a bit of company. An Iraqi Kurdish family of six spent two months in Sheremetyevo last fall before being moved to a holding facility for asylum seekers in November. According to Daria Trenina, one of Yasien’s lawyers, a Somali journalist has also been living there since last April; an Iraqi man was sent to Denmark on March 17 after spending eight months in the airport; and a Palestinian who had been there since August was recently sent home to the Gaza Strip.

Adding in Edward Snowden and a Japanese blogger who spent two months at the airport last summer claiming he was being persecuted in Japan, that makes 12 long-term residents in less than three years.

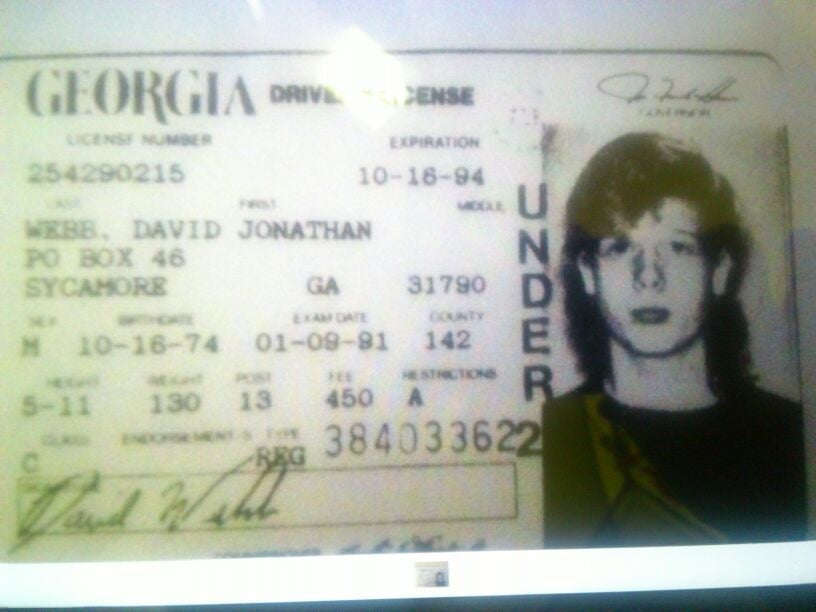

There may even have been a 13th. When Schwartz met Yasien in the terminal, he pointed out another man sleeping on the floor. He provided a picture of the man’s expired US driver’s license and a current photograph, as well as a handwritten letter he says was written by the man, in which he claims to be a US citizen, David Webb, suffering persecution in the US, and asks for asylum. Yasien said police came and took the man away on March 9. (Update: A spokesperson for the US embassy in Moscow said he couldn’t comment because of “privacy restrictions,” adding, “the Department of State takes our obligation to assist US citizens abroad seriously.”)

This spike in Sheremetyevo residents—before Snowden, the last case Quartz could identify was of an Iranian family that spent 11 months there in 2006-07—might be somehow related to tougher laws on illegal immigration passed in August 2013. The Civic Assistance Committee says expulsions have increased sharply, from 45,000 in 2012 to 198,000 in 2014.

Yasien himself has made several more attempts to get asylum in Russia while he waits. “There are no remedies under Russian law,” Trenina told Quartz. “We cannot achieve anything here – neither his access to [Russia], nor compensation for his deprivation of liberty and appalling conditions, nor refugee status.” Trenina hopes her application to the European Court will push the Russian authorities to sort out Yasien’s case. So far, she admits, that isn’t happening.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the official who took Yasien’s passport as “he” instead of “she.”