China has the most coal plants in the world—and half the time they’re doing absolutely nothing

There’s many a paradox in the world of coal. It’s the most polluting fossil fuel, and most governments agree that it doesn’t present a long-term solution to the need for energy to power an ever-more-developed and populous world. And yet, in many countries, more new coal capacity is being built than could ever be used if those countries are to hit their own climate targets.

There’s many a paradox in the world of coal. It’s the most polluting fossil fuel, and most governments agree that it doesn’t present a long-term solution to the need for energy to power an ever-more-developed and populous world. And yet, in many countries, more new coal capacity is being built than could ever be used if those countries are to hit their own climate targets.

Not only that: More capacity is being built than is even needed. Much more.

China is the biggest culprit when it comes to building expensive new power stations it doesn’t need. The average utilization rate of coal plants in China was just 49.4% in 2015, according analysis by the NGOs Greenpeace, Coal Swarm, and Sierra Club, published today. (pdf)

But the low utilization rates, which were 60% in 2011 and are predicted to keep going down, haven’t deterred builders, companies, and local authorities from enabling more capacity. ”China is effectively adding more than one redundant coal power plant each week,” the report’s authors write.

Coal use in China has actually dropped for the past two years in a row. Three factors play into that: a huge push for more renewable capacity; the structural change in China’s economy, which has seen growth slow; and the government’s concentration on improving the dire air quality.

So how come new plants are still being planned or built at all? One answer is the lag time for very large infrastructure projects like power stations: Those built last year were approved and begun many years before.

But another is about a shift in the way China is governed. In September 2014, the report notes, authority for issuing permits for new coal power stations passed from the national government to provincial authorities. In the nine months prior to the change, 32 permits were issued across the country. In the three subsequent months, 149 were issued.

The logic behind decentralization was to reduce interference and make markets more efficient, the authors note. But in practice “local authorities raced to approve projects they believe would stimulate local economies and benefit economic interests with influence at the provincial level.”

A further issue is so-called “captive” plants, built for use by one single factory or company with high energy use, like aluminum smelters. These power stations aren’t subject to the same rules as public plants.

Total coal capacity built or under construction since 2010 by one company, Shandong Weiqiao group, equaled that of the entire European Union during the same period, the authors said.

The national government has now stepped in, ordering provincial governments to suspend new approvals and building programs in some areas.

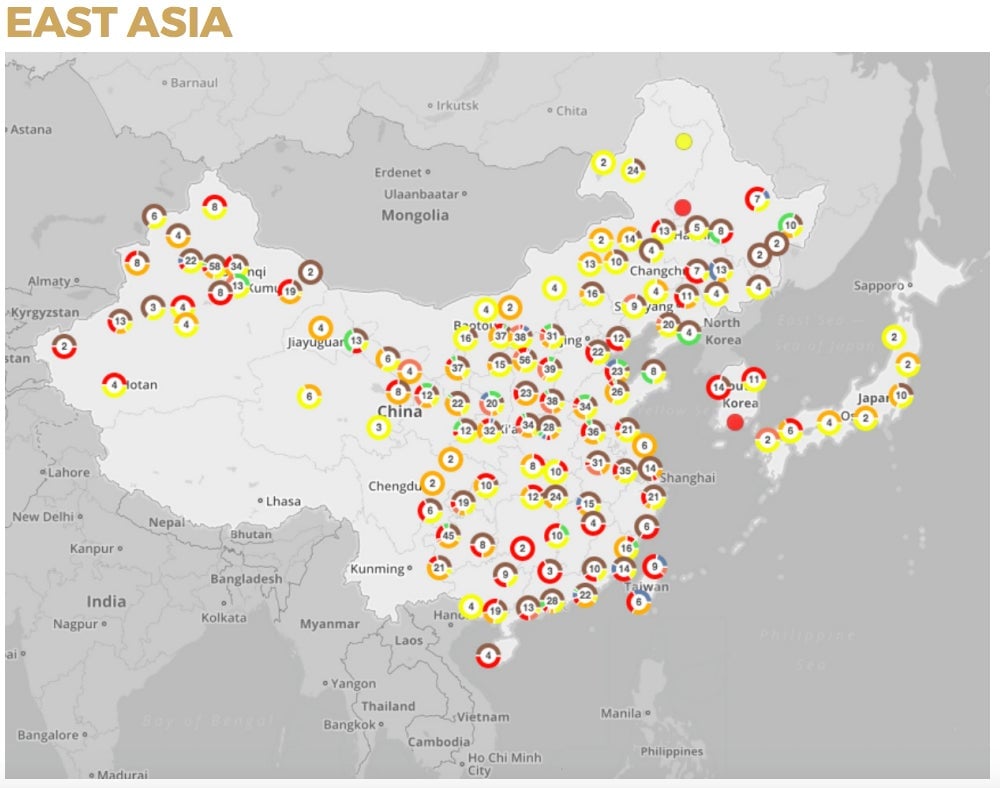

This map, from the Global Coal Plant Tracker database, showing coal plants in various stages of permit and build, gives a good indication as to why: