A 19th-century disease is on the rise in the UK—and nobody knows why

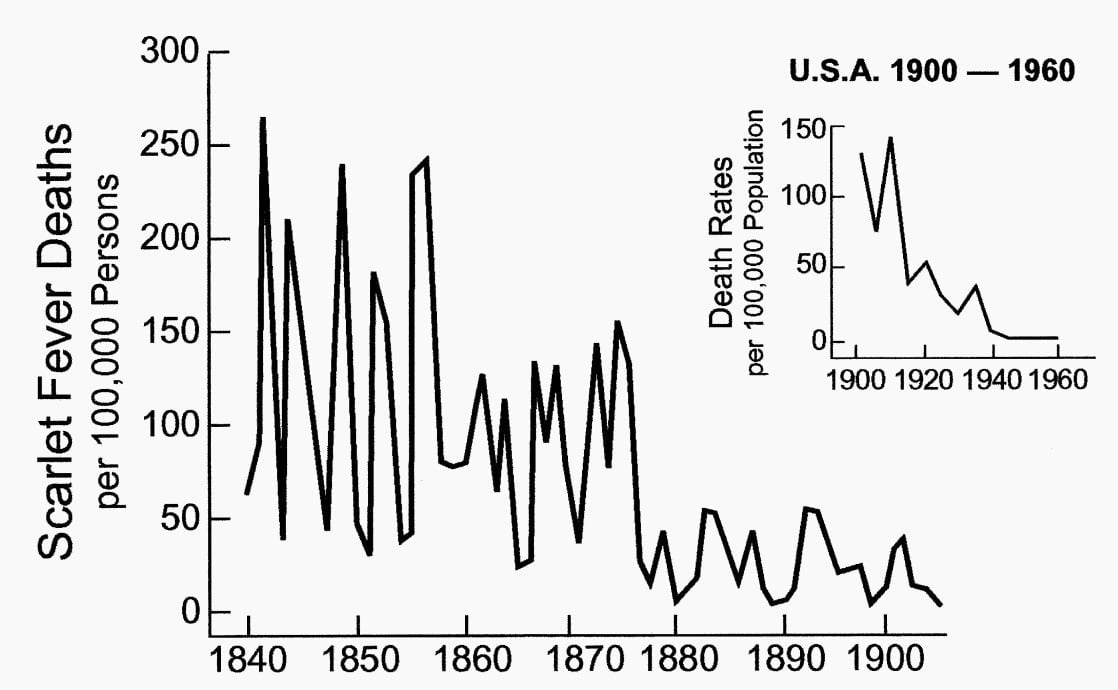

Scarlet fever struck fear in the hearts of Victorian-era Americans and Europeans. In the late 19th century, it was a leading cause of death in children—killing as many as a third of those who caught the infection.

Scarlet fever struck fear in the hearts of Victorian-era Americans and Europeans. In the late 19th century, it was a leading cause of death in children—killing as many as a third of those who caught the infection.

Look at the data from Boston (1840 to 1910) and the rest of the US (1900 to 1960):

After the invention of antibiotics in early 20th century, the disease came quickly under control. Both the number of cases and deaths plummeted.

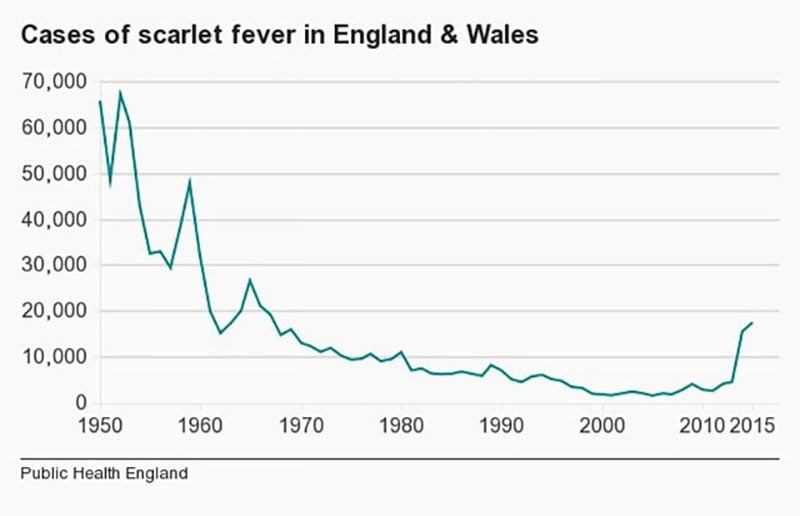

In the past few years, however, the disease is making a comeback. In 2011, Hong Kong experienced an outbreak that quadrupled in the number of scarlet-fever cases. And, since 2014, England and Wales has been hit by a big outbreak, too. This season, the number of scarlet-fever cases reached a 50-year high:

The fever is caused by Streptococcus bacteria and mostly affects children between the ages of two and eight. In rare cases, older children and adults can catch it too.

The outbreaks of the fever today have less severe effects than the ones Victorians suffered. No one, for instance, has yet been killed by the disease. And, yet, its return has baffled scientists.

In an analysis of 400 cases, researchers found that the strains of bacteria causing the outbreak are not much different than those found in previous years. There is also no dominant strain, which means that the blame can’t be isolated and identified. Fortunately, the strains that have emerged don’t shown any signs of resistance to drugs.

“It doesn’t seem that the bugs themselves are giving us any clues as to what is happening,” Theresa Lamagni, Public Health England’s (PHE) head of streptococcal infection surveillance, told the Guardian. The health agency expects to see more cases as the fever season peaks over the next few weeks.

A contagion’s evolution is a balance of lethality versus virulence. If a disease kills too many, it won’t spread as widely. PHE’s analysis has shown that scarlet-fever bacteria have evolved to become more virulent but less severe.

For now, PHE recommends to keep watch for symptoms: sore throat, headache, and fever with a sandpapery, fine, pink rash developing within a day or two. If a child shows these symptoms, a dose of antibiotics should eliminate the bacteria.