Hands on with Microsoft’s HoloLens: Augmented reality gets more refined but is still a little clumsy

A year ago at Microsoft’s developer conference, I tried on HoloLens for the first time.

A year ago at Microsoft’s developer conference, I tried on HoloLens for the first time.

While Microsoft’s augmented-reality goggles were unlike anything I had experienced before, HoloLens fell short of my expectations. As I wrote at the time, I was unprepared for HoloLens’s limited field of view:

[T]he layer of augmented reality (what Microsoft calls holograms) appears within a small box in the center of the display—far from an immersive experience. Think of it as a window: You can only see holograms through this window, but everything peripheral to it is plain old reality. It’s sort of like the AR version of tunnel vision.

Fast forward to March 30, 2016—the kickoff for Microsoft’s Build conference in San Francisco and also the ship date for the HoloLens development edition, available for $3,000.

Unlike my hands-on experience of a year ago—when Microsoft’s events staff barred electronic devices from the room and oversaw my every movement, making sure I wasn’t too rough with the hardware—I didn’t have to treat HoloLens like a delicate newborn lamb.

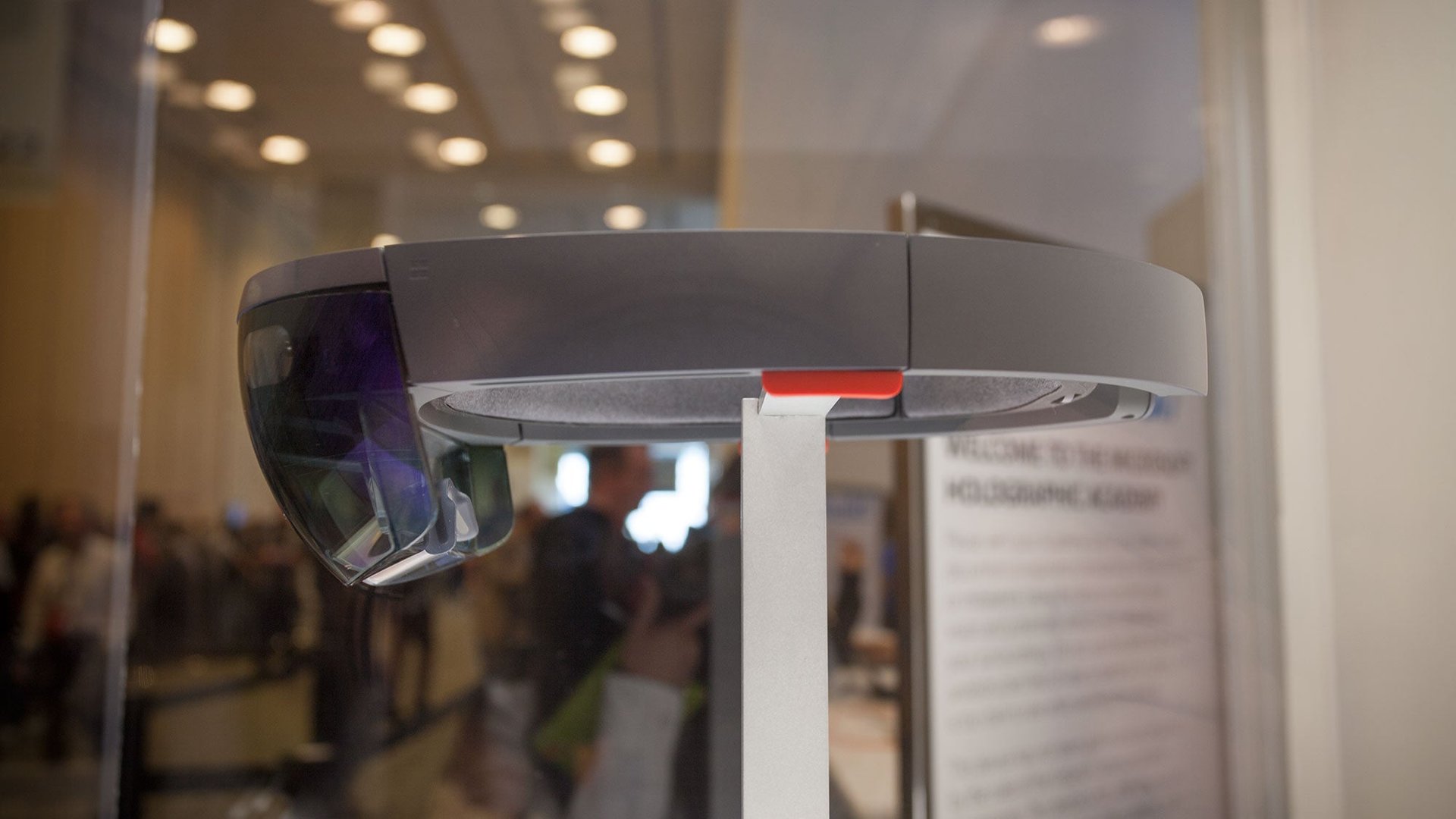

In my hour as a participant of Microsoft’s so-called Holographic Academy, I went through the motions of building holograms, adding interactivity to them, and seeing my creations come to life.

OK, so that might be a stretch. The graphics and scripts were already preloaded onto a machine running Unity and Visual Studio, so I merely followed instructions to click here, there, check some boxes, load the holograms onto the goggles, and preview what I just “built.” (Microsoft gave reporters a condensed one-hour, hands-on session. The regular academy is three hours long and involves writing code.)

The HoloLens models at Holographic Academy are not actual production models, but they’re pretty close save for minor details like the coating on the visor, a “HoloLens mentor” named Michael told me during the session. This is because Microsoft is shipping all available units, he explained, adding “they’re literally coming off the factory floor as we speak.”

But even now, AR tunnel vision remains a problem. Because the field of view is limited, holograms can get cut off depending on the position of the visor or movement of the wearer’s head. To fully appreciate the holograms around, HoloLens wearers have to move their heads around a lot. The headset doesn’t detect and adjust for eye movements. To see a hologram placed on a coffee table, for example, wearers need to physically tilt their heads down.

For Build this year, Microsoft had far more HoloLens capabilities to show off. Throughout the session, I progressed from making a single hologram that only I could see to more dynamic holograms that my fellow attendees and I could all see and interact with. Our gestures—an air tap (raising and lowering the index finger) and blossom (opening up a closed palm toward the ceiling)—and voice commands allowed us to make selections, reposition holograms, and shoot at each other’s holograms.

Though holograms are visual, HoloLens uses spatial sound, similar to VR headsets. This means that even though the source of the audio is within the headset, it appears to come from the hologram itself. So as I walked past a hologram, I noticed it more prominently in one ear, and when I’m farther away, the audio is more faint.

Compared to the models of a year ago, today’s HoloLens is more refined in how it calibrates the distance between your pupils when you first put it on. Instead of using a ruler or external device, Microsoft built a game-like calibration mode, asking users to align their index fingers to a shape they see on the display and air tap. The calibration process also serves to familiarize users with the air tap, by far the most common gesture.

Putting on HoloLens for the first time can be a clumsy experience. The goggles have some heft to them, and the people who ran my Holographic Academy session advised attendees to align the headset to their hairlines. I found that position extremely uncomfortable. Though it wasn’t resting on my face like a VR headset, it was heavy, which I compensated for by tightening the strap. Partway into the session, Michael told me that he prefers to rest it higher on his head, almost like a crown. For me, that instantly transformed what was turning into a miserable demo to something I could enjoy.

My eyes felt strained and the signs of a headache emerged at the beginning of my session. Another HoloLens mentor, Shirin, thought it was because the calibration mode recorded incorrectly. That wasnt the case, and the headache subsided around the time I figured out how to wear the HoloLens more comfortably.

HoloLens is not yet a full-fledged consumer product and obviously has room to improve. But one pain point for me was the navigation. When I exited out of my demo, I had to wade through several menus to resume where I left off. Air tapping is also less precise than clicking a mouse, so it can be a confusing experience to get back to the previous program. Perhaps a shortcut button could help those who are flustered after accidentally exiting their programs find their way back.

Holographic Academy is structured to end with a bang. All the exercises build on top of the previous ones, ending with a shooting game (shoot by air tapping). The finale was fun. In my group of six, we shot at each other’s avatars (all named Polly, short for polygon) before a mentor suggested we see what happens when we shoot at an energy orb hologram placed on the coffee table.

Eventually the orb exploded and revealed Polly’s underworld. It was fascinating to see the layers holograms can have. Beneath the orb was a tunnel with more Pollys floating by, waiting to be shot at with fire balls, which bounced off the walls when we missed. Polly’s Underworld was certainly more exciting than the architecture and construction demos I passively experienced last year.

But then I took a step back, literally, and saw what we looked like. I couldn’t help but think there was something innately silly about what we were doing. Because this, my friends, is the future of augmented reality: