35 years later, the man who shot President Reagan is close to being free

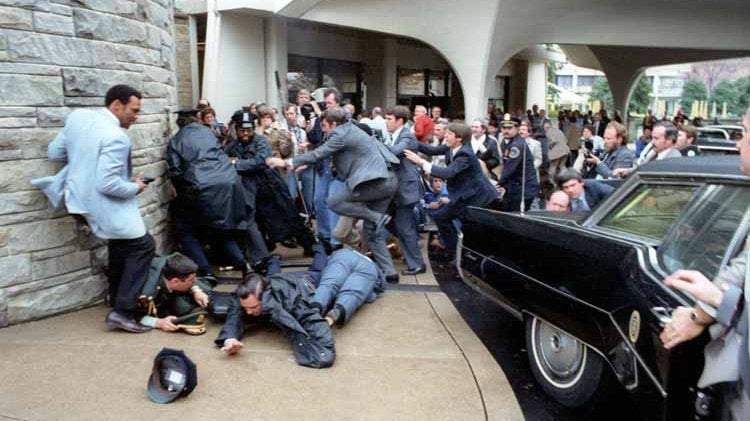

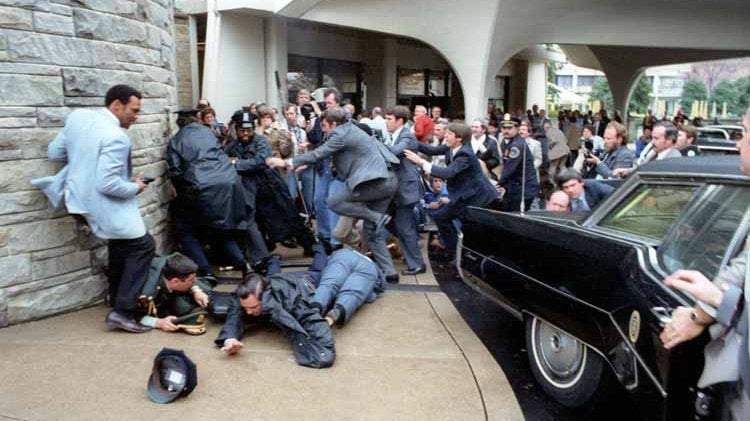

In 1981, 35 years ago this week, John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Reagan in an effort to impress actress Jodie Foster. He began shooting from just 10 feet away, leaving Reagan with a bullet in his lung and three others with injuries. Press secretary James Brady suffered brain damage and died as a result of the shooting in 2014, in what was ruled a homicide.

In 1981, 35 years ago this week, John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Reagan in an effort to impress actress Jodie Foster. He began shooting from just 10 feet away, leaving Reagan with a bullet in his lung and three others with injuries. Press secretary James Brady suffered brain damage and died as a result of the shooting in 2014, in what was ruled a homicide.

In the ‘80s, it was expected that the man who shot the President would be sent to prison for life, or else face the death penalty. Yet, though the insanity defense is rarely successfully used in the US, Hinckley was found not guilty for exactly that reason.

He’s spent the years since at St Elizabeths Hospital, a psychiatry facility in Washington, and since 2013 has been allowed to spend 17 days of every month at his mother’s home, in southeast Virginia. Hinckley is subject to numerous conditions, and is monitored by the Secret Service, but has been permitted unsupervised outings since 2003. While in Virginia, he visits friends and takes daily walks, in an effort to integrate himself with the community. Recently, Hinckley’s lawyers argued that he should be given full convalescent leave from the hospital.

His attorney, Barry Levine, who rarely speaks on the case, tells Quartz that the mental diseases from which Hinckley suffered in 1981 “have been found by the court to be in full and stable remission for decades.” Hinckley is “harmless,” adds Levine, who says no mental health-professional connected to the case disagrees that, were Hinckley’s mental health to deteriorate, it would be slow. “It would be readily discernable and there would be plenty of time to intervene.”

Levine says that from a mental health perspective, Hinckley’s case is clear-cut. He adds:

“The likelihood of danger is remote in the extreme. This is an easy one in some respects. Yet the political fallout of the crime is so great that these experiments in freedom, which the court has continued to allow, have been very incremental and slow.”

A shocking verdict

Since the shooting, Hinckley’s experiences in court have not gone according to expectations. At the time of his trial, Alan Stone, professor of law and psychiatry at Harvard Law School, went on national television to predict, “There was no chance he’d be found not guilty by reason of insanity.” Typically, the insanity defense is only successful when the prosecution agrees to it—not when it’s contested. Valerie Hans, law professor at Cornell Law School, conducted a study on the public’s reaction post-verdict, and says that many were furious that attacking the US leader had seemingly gone unpunished.

“There was a sense among the public that this was the wrong outcome, even if the details were lost on them,” she says. Many seemed to think the insanity defense was “quite literally getting away with murder.”

A shift in the law

Though it was difficult to successfully plead not guilty by reason of insanity in 1981, it became even more challenging since Hinckley’s trial. In particular, the burden of proof shifted, so that instead of the prosecution having to show beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant was sane, it became the role of the defense to prove that the defendant was criminally insane. This marked a major turning point in US insanity defense law, says Hans.

“We had been moving in a direction towards greater accommodation of people with mental illness and there were expansive insanity defense laws,” she says. “After his verdict, the federal government and the state government wound up modifying and restricting further what could happen.” In Delaware, for example the state modified the not guilty by reason of insanity defense within days of the Hinckley verdict, creating the option of “guilty but mentally ill.”

It’s possible that this shift in the burden of proof would have made a dramatic difference to Hinckley’s verdict. Stephen J Morse, professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, says that while he read the trial transcripts he did not attend the trial, and so his opinions are purely speculative, he believes that Hinckley could have lost if he’d been tried in a local rather than federal jurisdiction. In a local jurisdiction at the time, Hinckley’s defense attorneys would have had to show on “a preponderance of the evidence” (i.e. more likely than not) that he was criminally insane—a markedly different burden from the prosecution having to prove sanity beyond a reasonable doubt.

The system working at its best

But while the verdict could have so easily gone another way, Hinckley was found not guilty. And, in the years since, has received strong psychiatric support.

Stone says that, compared to many other mentally ill criminals in the US who are possible contenders for the insanity defense, Hinckley has received excellent treatment and supervision.

“I think the system rarely works this way but this time, with all the special attention, it worked very well,” he says. “I think it’s amazing that somebody who killed people, maimed people, shot the president of the United States, was able to be restored to sanity, and allowed to leave the hospital, if only partially.”

Unfortunately, this is not the case for many others. The system of public care for the mentally ill in the US is “in terrible shape,” says Stone, and that there’s little hope of replicating Hinckley’s treatment. “We don’t have the resources, in this wealthy country, to treat anybody else the way we treated Hinckley,” he says.

A return to sanity

Following the help he’s received, psychiatric evaluations suggest that Hinckley is no longer suffering from the mental illnesses he experienced 35 years ago. Levine says that others with mental illness who commit criminal acts deserve the same rehabilitation process.

Unlike physical health, where it’s widely understood that it’s possible to recover from a broken arm or heart attack, Levine says that many seems to believe a mental disability never fades.

“They think that if you have that, you’re condemned to suffer from it forever, and because you’ve committed a grievous criminal act, it’s likely you’ll do that again,” he says. “That’s just wrong, but that’s the common perception, and that’s why there are so few people who get the benefits that John had.”

Stone says that he and most other psychiatrists view serious mental illnesses as more akin to diabetes—something that should be treated for life, but can be managed.

“If the patient has insight into the fact that they have a mental illness, are willing to take their medications, and work with doctors, then it can be controlled the same way that diabetes can,” he says.

Though only a psychiatric professional can give a confident assessment of Hinckley’s health, court documents and his time away from hospital suggest that he’s no longer a danger to the public.

Morse, who is not involved in the case, speculates that, were Hinckley an ordinary citizen rather than the man who shot President Reagan, he “might very well have been released before now.”

Politics has undoubtedly shaped this high-profile case, and the judge has been cautious in gradually allowing Hinckley greater freedom. But perhaps, Morse suggests, there will be less pressure to keep Hinckley confined following Nancy Reagan’s death.

Of course, in a country with typically onerous prison sentences, it might seem strange that a man can shoot the president and walk free. But, as Hinckley was found not guilty, Morse points out that he cannot be legally punished.

“The judge or public may believe this person should not have been acquitted by reason of insanity, and so they may feel this person should be kept longer,” he says. “But that’s not an adequate justification under law. My concern, both legally and in terms of his mental health, is whether he needed to be hospitalized for as long as he has been.”