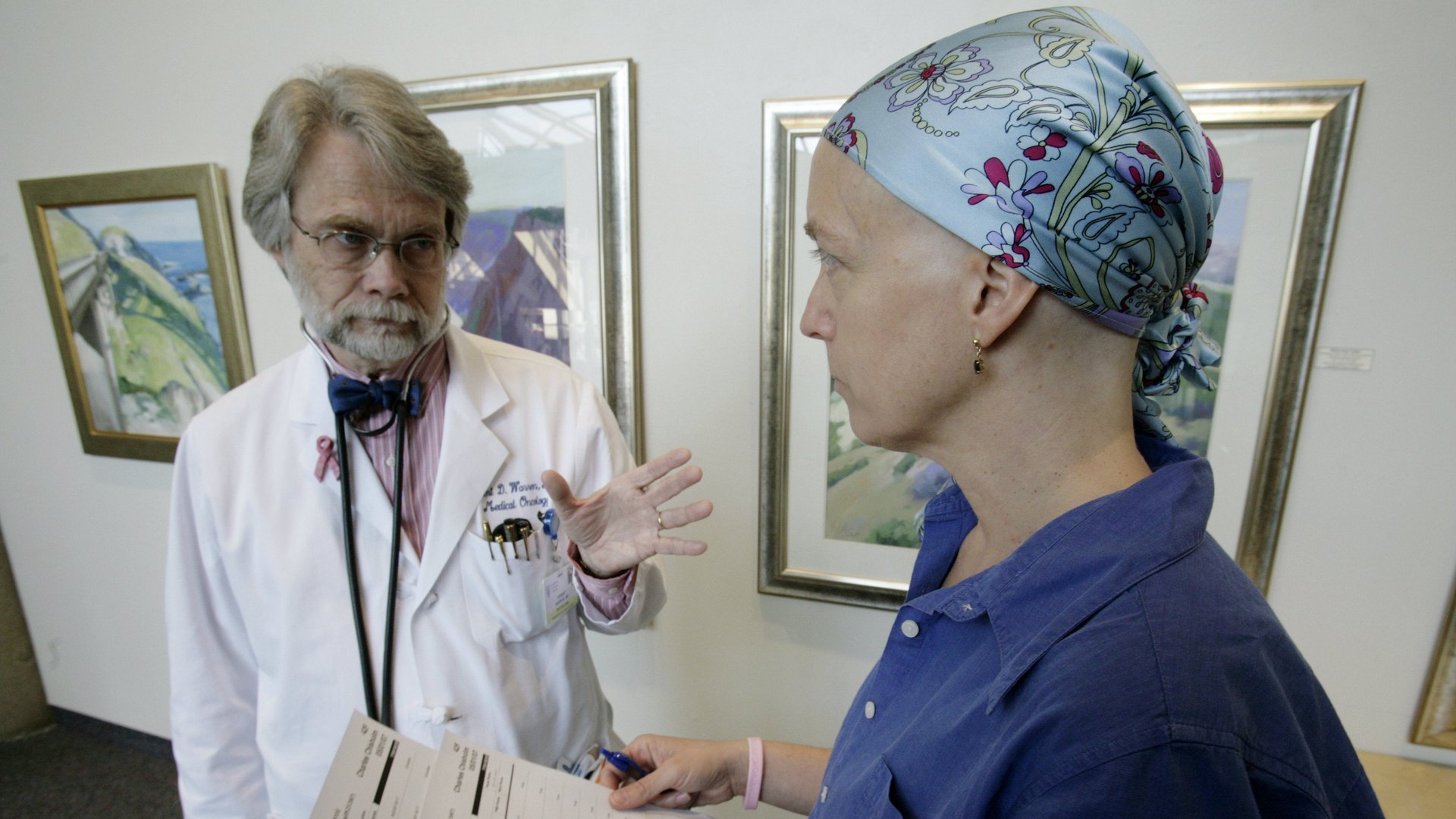

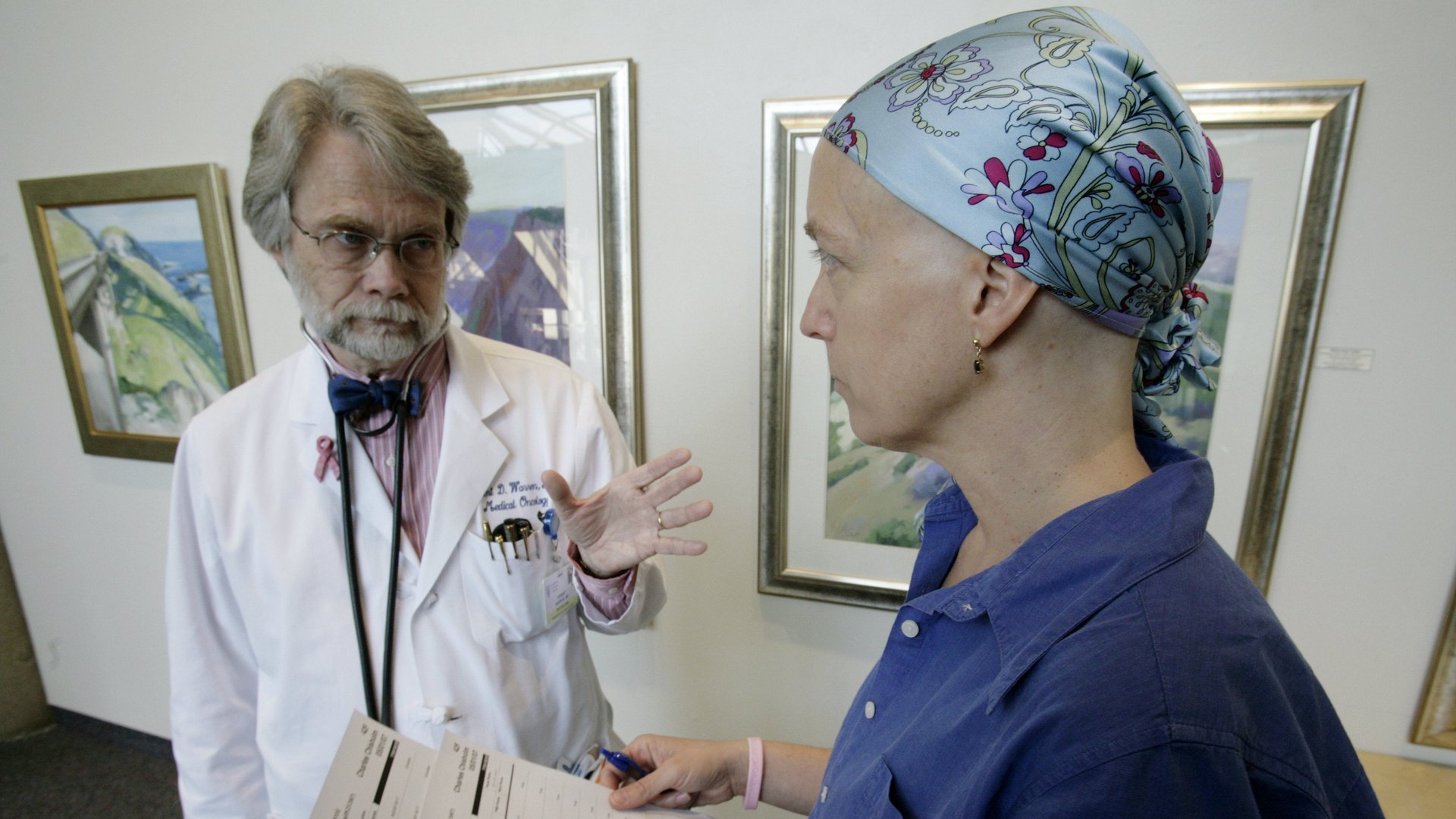

At Stanford’s new cancer center, patients interview every new hire

Sometimes it’s the patient, not the doctor or hospital administrator, who knows best. Stanford Cancer Center South Bay has espoused this ethos in every aspect of its development, including having patients conduct interviews for hiring.

Sometimes it’s the patient, not the doctor or hospital administrator, who knows best. Stanford Cancer Center South Bay has espoused this ethos in every aspect of its development, including having patients conduct interviews for hiring.

As Katie Abbott, the senior program manager for business operations, puts it: “Being in healthcare as a clinician or an administrator doesn’t mean you’re saved from being a patient. But we still become blind a bit and miss things—it really takes those eyes of other folks to help us design better.”

The center, which opened in June, employs patients and family members from Stanford’s Palo Alto center, as well as a local community cancer practice, on its 20-person Patient and Family Advisory Council in this process. The center was adamant about having 100% of staff interviewed by a patient, a family member, and someone from the non-hiring leadership team. Over the course of six months, the committee hired 250 people for the center and used this process on each one (except doctors)—from nurses to the cafe staff. The hiring managers used direct quotes from candidates’ interviews to assist in their decision.

Abbott said patients ask completely different questions of prospective staff and have provided crucial perspective for the center to carry out its mission to be patient-centric. The Affordable Care Act has changed financial models in healthcare, making patients the direct consumer. And to cater to this market, more facilities in the US are being designed to focus on patient experience and quality of care.

“You can’t necessarily measure” the effect the patients’ involvement has had, Abbott said. “But when you walk in the building, it just feels different.”

I talked to Abbott at the Health Experience Refactored Conference in Boston about this approach. Here’s how patients and family became an integral part of the interview process, one that’s still in place, as explained by Abbott. (The following is edited for length and clarity.)

They made the process nimble. “In the beginning, [the hospital staff] was really reluctant to participate. They thought this was going to be an additional step that would slow down the hiring process and we might be losing our best candidates. So we set up a framework so that wouldn’t happen. We made ourselves very available so if somebody said, ‘I need this interview to be done this afternoon,’ we were able to be nimble enough to do that.'”

They provided adequate training. “We did train our patients and families first so they went through an interview bootcamp with HR. They learned what to ask, what not to ask. You can ask about experience; no, you cannot ask if somebody is pregnant right now. That also helped the patients and families feel more comfortable. Some of them were executives themselves and had done interviews before. Most of them who participated had never done an interview in the past. Part of it was getting them comfortable and confident and up to speed. The other piece was being able to use a few of the quick wins [in using this process] and first interviews as a platform to show just how beneficial their perspective was.”

Patients and family members became the deciding factor. “In the beginning, managers sent us their top candidates and it was very clear they’d made the decisions of who they wanted to hire. We would send them the feedback: 90% of the time, patients and families were so enthusiastic about having these folks join the team. But for that other 10%, if the interview didn’t go as well or there were just quotes that these candidates had said that didn’t quite feel patient- and family-centered, we would send that feedback to the hiring managers. They would say ‘Oh my gosh, I knew this person technically was great, they could do the job and even from a human-centered standpoint, I thought they were great, but there was something that I couldn’t quite put my finger on.’ Oftentimes the feedback we would capture was solidifying what their gut already had told them. They were a great candidate, but something just wasn’t quite a great fit. As we moved on, we found that people were actually sending us their top two or three candidates and they would say, ‘They’re all great, I need the Patient and Family Advisory Council to pick.'”

They learned from the questions their patients asked. “One of my favorites, and this was an interesting one for folks to answer, was ‘What’s one thing about the culture where you work now that you’d like to bring to the new cancer center and what’s one thing that you’d like to leave behind?’ It made candidates a little uneasy, but it gave them permission to talk about the things they were proud of and they hoped to bring to the new site, and things that were big opportunities for us to problem-solve together. That was one of my favorite questions that our volunteers asked, and now I ask in almost all of my interviews as well.”

If candidates weren’t comfortable being interviewed by patients, they probably weren’t a great fit. ”Some of them even said things like, ‘I don’t really like being around patients.’ They may have been a lab tech in the back, but to me, every vial of blood, every specimen that comes through is a patient. That candidate may have never admitted that to the hiring manager. When they were able to say that in front of the patients and us [staff, it was clear that] this wasn’t a great fit for this person either. They need to be excited about the culture that we’re trying to build in order for them to be excited about their role as well.”

Correction: A previous version of this post stated that doctors were interviewed by the patient and family advisory council members.