To stop relying on Western hand-me-downs, African countries are importing Chinese textile companies

Kigali, Rwanda

Kigali, Rwanda

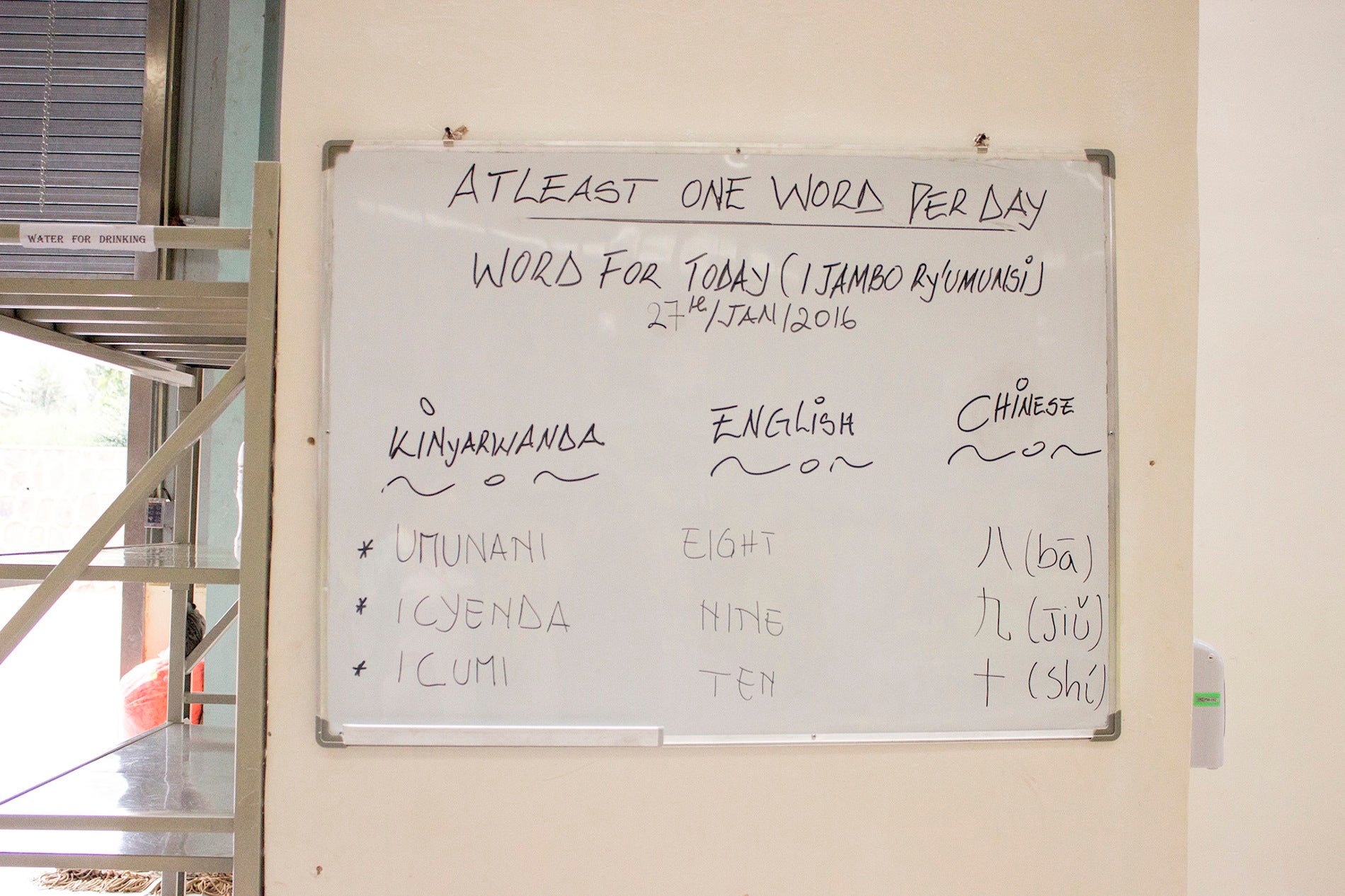

Every day the workers at C&H Garment Factory are required to learn a few words of Chinese. Today’s lesson, written on a whiteboard at the back of a humming factory floor, is the numbers 8, 9, and 10—written in Kinyarwanda, English, and Mandarin. ”We’re a Chinese company so we want to introduce a little Chinese culture to them,” the textile company’s owner, Candy Ma, tells Quartz.

Like many workers in China, the staff are required to do group exercises before beginning their day. Signs with the words “diligence,” “quality,” and “responsibility,” written in English and Chinese, hang from the rafters. Chinese and Rwandan flags fly outside the glass-paneled building that houses C&H, which began operations last year in the Kigali Special Economic Zone on the outskirts of the capital.

Ma’s factory is the culmination of recent government efforts to establish a Rwandan textile industry and expand the country’s almost nonexistent manufacturing sector. For Rwanda, it’s also about moving on from being another third-world African country dressed in hand-me-downs donated from Western countries.

Ma has partnered with the Rwandan government to train locals in garment manufacturing, making clothing to sell locally as well as to export. One of the project’s goals, according to Rwanda’s minister of trade, is to stop relying on second-hand clothing and save the “struggling dignity” of the Rwandan people.

“It’s about being capable and self reliant. We want to be independent… wearing clothing that was owned by another person, is this dignity? Can this make you proud?” Gerald Mukubu, head of Rwanda’s Private Sector Federation, which is part of the textile initiative, tells Quartz.

Second-hand clothing in Rwanda, better known as chagua, or ”to select” in Kiswahili, another language spoken in Rwanda, is sold in open air markets, shops, and by hawkers along the streets. Elsewhere, these clothes are known as “mitumba,” or “bundle,” referring to the plastic packages of donated clothing from wealthier countries that arrive in the region. More than 70% of clothes donated globally end up in Africa, according to the nonprofit Oxfam. Rwandans spend more than $100 million a year importing clothing, both second hand and new.

It’s not only worn by the country’s poorest; most middle class Rwandans wear a mix of new and recycled clothes. Mukubu says that while he doesn’t wear much second-hand clothing, many of his colleagues and friends do. Tharcisse Baranyeretse, a translator in Kigali, commented to Quartz that his entire outfit—a crisp button-up shirt, slacks, with a matching leather belt, and gleaming shoes—is all chagua. “Everyone wears it,” he says.

The East African Community (EAC), which includes Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Burundi, as a whole has proposed a ban on second hand clothing by 2019. They hope the ban will help domestic textile manufacturers. Officials also claim that second-hand clothing is unsanitary and can lead to diseases. (There is little research that says second-hand clothing, if cleaned and stored properly, is unhygienic).

The campaign isn’t restricted to East Africa. South Africa has had a ban in place for decades. Ghana barred the sale of second-hand underwear in 2011. Malawi, and Zimbabwe have also been considering bans. Used clothing imports are also outlawed in the Philippines.

This is where industrialists like Ma come in. An energetic petite woman from Xi’an in central China, Ma moved to Rwanda two years ago upon invitation from Mukubu’s Private Sector Federation. Before that she had set up shop in Ethiopia, one of the first African countries to become a base for Chinese textile manufacturing, where she first heard Rwanda was looking for investment. She also ran a mobile phone factory in Kenya.

Ma says she was attracted to the Rwandan government’s business friendly approach—taxes are low, she’s only required to pay income tax—the cleanliness of the capital city Kigali, and the people she encountered on a scoping mission. America’s recent renewal of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which gives African textile producers duty-free access to US markets for 15 years, has been another incentive.

“I have a lot of experience doing business in Africa and thought, ‘This could work,'” she says.

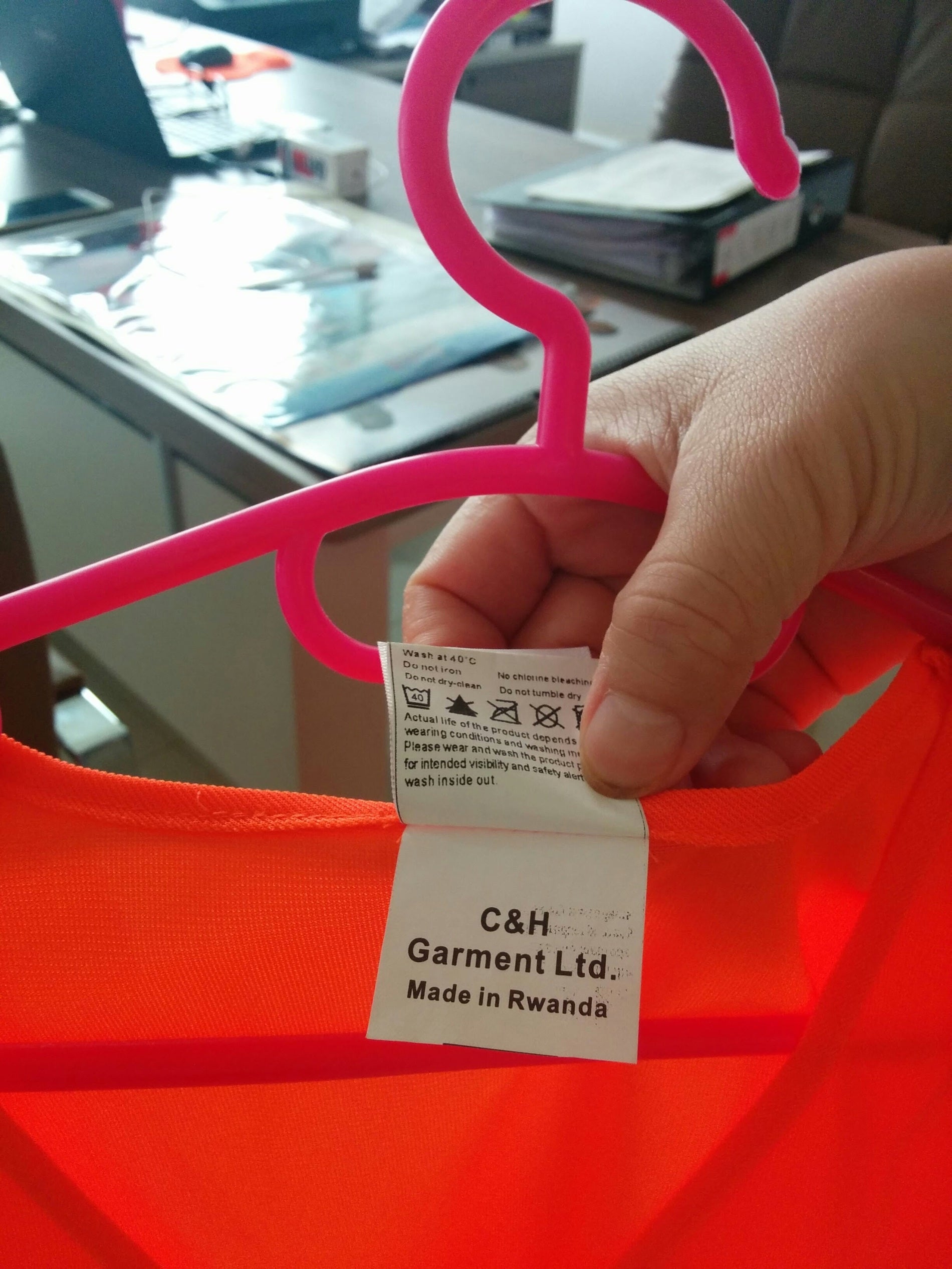

So far, C&H’s workforce of 800, which includes trainees and already trained workers, are making police uniforms, safety vests, and most recently military kit for the Rwandan security forces. C&H’s main product, uniforms, are mostly exported to Europe and the United States. They are branching out into underwear, which Ma plans to sell locally.

Ma’s remit is to help build a foundation for the industry. Technicians from Kenya, once home to a thriving textile scene, have been brought in to help teach the group how to sew, cut material, and inspect the production line. Ma is also holding a management course. A professional group, the Rwanda Association of Tailors has been set up to help promote the sector.

“It won’t benefit us at all”

It’s Kigali’s hope that more operations like Ma’s will come and eventually replace the need for the second-hand clothing market. But getting rid of chagua won’t be easy.

In the Biryogo Market, in the Muslim quarter of Kigali, there are hundreds of stalls with children’s clothes, nightgowns, and lingerie strewn across cheap wooden tables. The clothes here are from Canada, the Netherlands, the United States, and Europe. Stall owners estimate there are as many as 1,000 chagua sellers here.

“The way you can judge the quality is by the look and feel,” says a woman seated on a stool next to a stack of clothing still folded and packed in a plastic bag. She rifles through a pile and pulls out a striped polo, made with a thick heavy cotton, as demonstration. “Those clothes they want to sell us from the factories are made in China. They’re very fake and people don’t trust them,” she says, declining to give her name for fear of punishment from authorities.

Like many of the sellers here, she has been in this business for a long time—30 years of supporting five children through sales of chagua. When asked what she thinks of the government’s concern for the dignity of its people and hygiene issues of recycled clothing, she accuses the government of conspiracy.

“The government is lying, lying, lying. There’s something else behind it,” she says. She has heard about the proposed ban on television. “It won’t benefit us at all,” she says.

For many, used clothing is all they can afford. For others, shopping chagua is a way to curate their wardrobe and ensure they aren’t caught wearing the same thing as anyone else. At a recycled clothing shop in central Kigali, a smaller selection of clothes are on display, carefully hung in rows or folded into neat piles on a set of shelves. A young man in a denim shirt studded with rhinestones and paneled jeans scoffs at the idea of buying only new clothes. “The new clothes are like uniforms. It looks bad, like we are a sports team or a group of church singers.”

Critics say banning second hand clothing won’t necessarily boost local industry. And operations like Ma’s won’t be enough to replace chagua; most of the C&H products are for export. Others say that used clothes will likely be smuggled in, as plastic bags have been since the Rwanda declared them contraband. Higher taxes on imports of second-hand shoes, introduced this summer, has so far failed to seriously dent business, according to traders.

Marc Vooges, director of Sympany, a Dutch charity that recycles used clothing, says the ban also limits citizens’ rights to make their own decisions. “You disrespect the choice of your citizens who are choosing those second hand clothes instead of new clothes which are available for them. There must be a reason for that. Respect that reason,” he says.

“Made in Africa, with China”

Other African countries have already attracted Chinese textile makers. Chinese shoe assembly operations in Ethiopia have inspired more industry around it like leather processing, recycling old plastic bags into plastic goods, as well as more shoe factories from other countries. Huajian, one of China’s largest shoe producers, is expanding in Ethiopia and in East Africa. Other Chinese investors have expressed interest in setting up shop in an industrial park in Tanzania, turning local cotton into cloth.

Shoes and clothing may be just the beginning. As labor costs in China have risen over the last decade, prompting Chinese factories to seek cheaper locations or move into higher-end manufacturing, African officials have hoped some of that manufacturing might relocate to Africa. Lately, Chinese officials have been dangling that prospect even more.

At a high level China-Africa summit, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, in Johannesburg late last year, China’s ambassador to South Africa Tian Xuejun told a press briefing, “We want to change the narrative from ‘made in China’ to ‘made in Africa, with China.'” In one of conference sessions titled, “Catapulting the African industrialization renaissance,” Chinese officials pledged to help the continent reach its goal of seeing manufacturing account for more than 50% of GDP by 2063.

For now, industry accounts for just 10% of the Africa’s overall GDP, the same rate as it was in 1990, according to John Page, a Brookings Institution fellow and former chief Africa economist for the World Bank. As China moves out of low-end manufacturing, there may now be a chance for Africa to gain some of that business. ”There is a window of opportunity,” Page says.

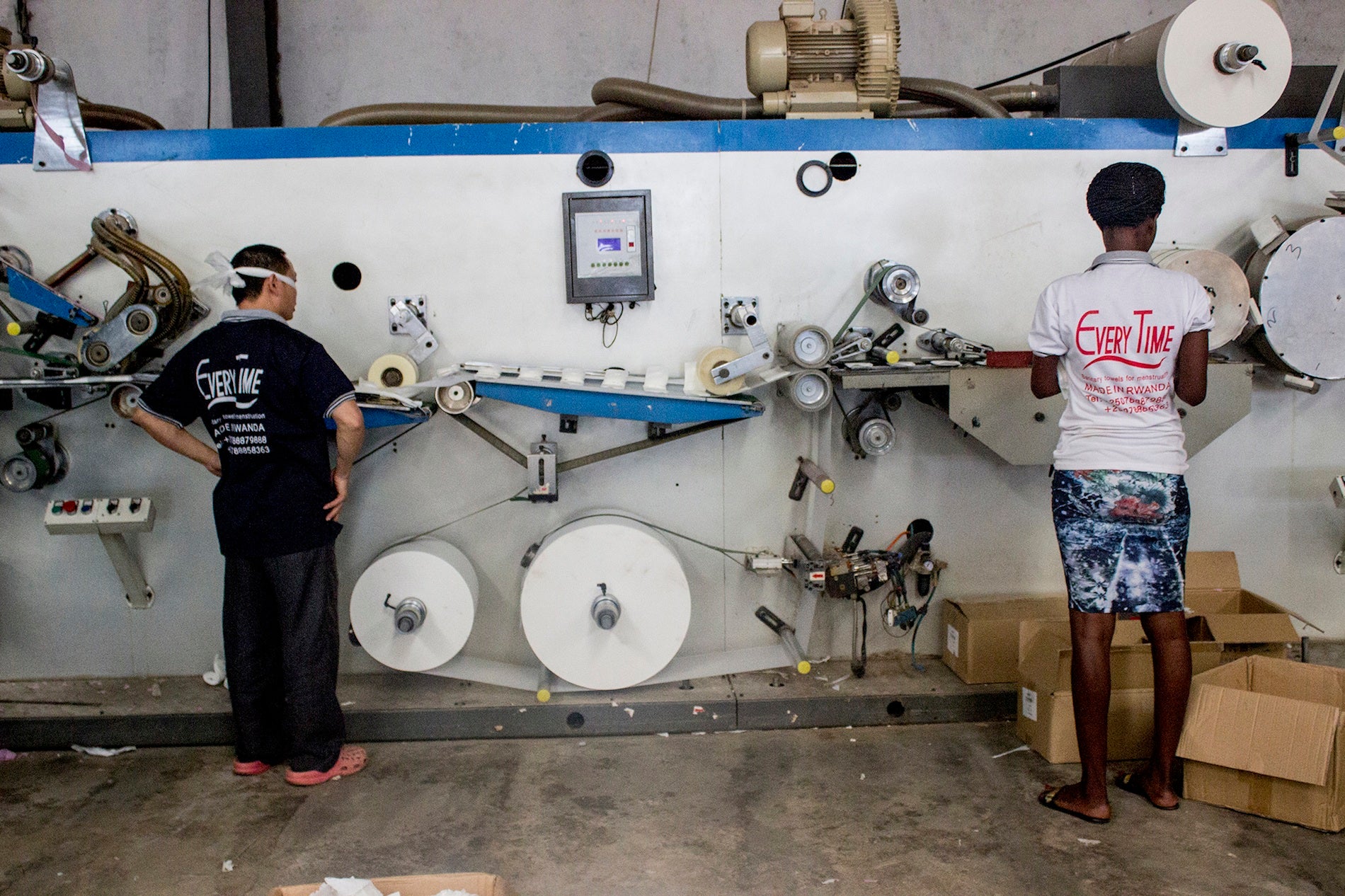

Chinese investment in African manufacturing has already grown, and examples of Chinese factories producing in Africa are becoming more common. In Kigali’s special economic zone, another Chinese company, Beijing Paper, produces sanitary napkins under the brand “Every Time,” sold in stores locally. A nearby Chinese company makes wooden doors. Ma is considering reopening the mobile phone factory she attempted in Kenya five years ago. China FAW Group, one of China’s biggest auto makers, now has an assembly plant in South Africa.

In some cases, Chinese investment in African textile industries has actually hurt local producers. In Ghana, Chinese manufacturers are outcompeting artisans and putting them out of business. This past year, Nigerians have been protesting Chinese who are manufacturing their traditional fabrics and selling them at cheaper prices.

Some initiatives to inspire manufacturing have been underwhelming. At the workshop of the “China Rwanda Bamboo Project” in Kigali—a Chinese initiative to train local workers in bamboo manufacturing—three young men and a woman nap on a piece of foam meant to be used for furniture. The room is littered with unfinished bamboo screens, baskets, and lanterns. The power is out so the staff have stopped early.

“They don’t work. You teach them one thing, they learn it, and the next day they come back and they’ve forgotten,” says Huang Daizhong from China’s Zhejiang province, who has been leading this project for the past six years. The results have been meager. So far, just two factories are making use of the bamboo processing techniques he has taught them—both are making toothpicks.

In Huang’s home province of Zhejiang in eastern China, mass production of bamboo handcrafts was the first step in establishing a textile industry and training a largely rural population with few technical skills. (Textile producers now account for 10% of that province’s gross industrial output.) Huang had hoped the same principle would work in Rwanda, but has been disappointed.

“Rwanda hasn’t reached this point of being able to manufacture yet. It will still take many years,” he says.

For a country’s civilization

Rwanda isn’t the easiest place to start a garment industry. Transportation to the land-locked country is expensive—it costs more to send a container from Kigali to Kenya’s port city of Mombasa, where all of C&H products depart from, than to send goods from Mombasa to Guangzhou in southern China. Ma has to import all of her materials, including the cloth, string, and the zippers.

Still, Ma, who has been working in textiles in developing countries for more than 16 years, believes she is uniquely equipped to meet the challenge. Unlike Huang and other Chinese managers who grow frustrated with their local staff, she says she tries to understand her employees and how they work best. “You just have to know them,” she says.

The company is not yet profitable, but she expects this year to be better. Ma anticipates more Chinese production moving to Africa as Southeast Asia becomes saturated with Chinese factories searching for cheaper locations. She will still have been the first in Rwanda.

And perhaps most importantly, she relates with the government’s campaign to wean the country from chagua.”In China during the 1980s there were also a lot of people wearing old, second-hand clothing. Now, not a single person is wearing recycled clothing. I think that for a country’s civilization to progress you do need to stop that.”

This story is part of a series about China’s engagement in Rwanda and reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s African Great Lakes Initiative.