From red-haired foreigners to Soviet Grandpas—a look at Chinese cartoons about spies

China routinely warns its citizens about the dangers of spies, foreigners—and foreign spies—with media reports about captured operatives, or directives informing people how to spot them. Now, a recent propaganda initiative on the subject has arrived, featuring bright colors, speech bubbles, and a riveting storyline of romance.

China routinely warns its citizens about the dangers of spies, foreigners—and foreign spies—with media reports about captured operatives, or directives informing people how to spot them. Now, a recent propaganda initiative on the subject has arrived, featuring bright colors, speech bubbles, and a riveting storyline of romance.

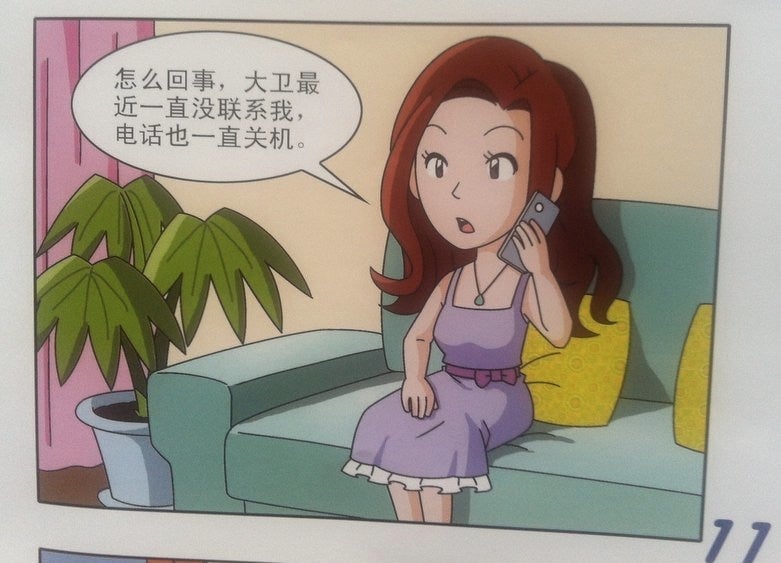

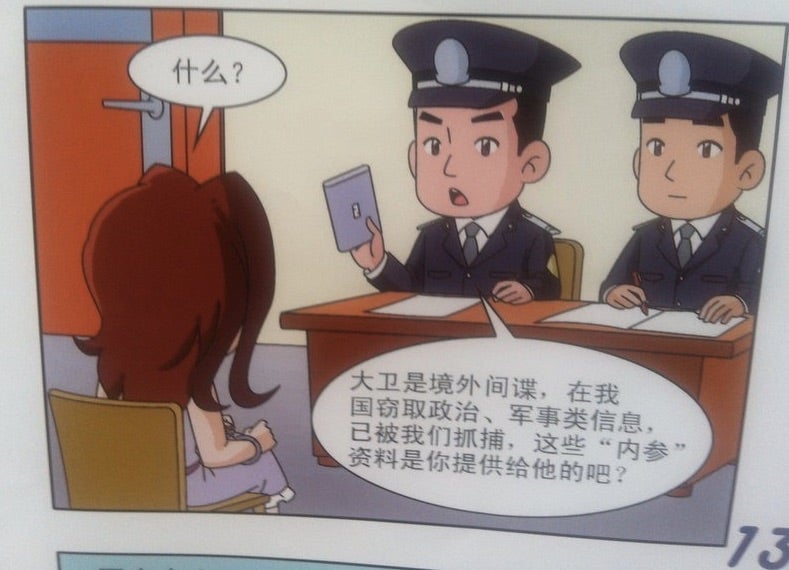

Last week, as part of China’s first-ever National Security Education Day, Beijing district government officials hung posters around the residential community of Xicheng warning women not to date foreigners. The posters featured a 16-panel comic telling the story of a government employee who falls for a red-haired foreigner claiming to be an academic.

The female employee and the academic begin dating. As they spend time together, the scholar persistently asks for “internal references” from the woman’s job, but when she complies, he disappears. Officials from China’s Ministry of State Security later tell her she was dating an overseas spy.

Meanwhile, in a series of viral videos released last week, China’s Ministry of State Security depicted popular Western comic book figures like The Joker and Wonder Woman as foreign spies attempting to obtain state secrets. “If you discover there are elements working to undermine national security, immediately report them to the relevant authorities and provide evidence,” states the narrator.

These cartoon warnings are a throwback to an earlier era. During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, the target of propaganda campaigns was more often “counterrevolutionaries”—Chinese citizens who failed to display enough loyalty to Mao or the party, even if their only offence was coming from a wealthy family. People were encouraged to report friends, family members, and acquaintances for perceived infractions against Maoist ideology.

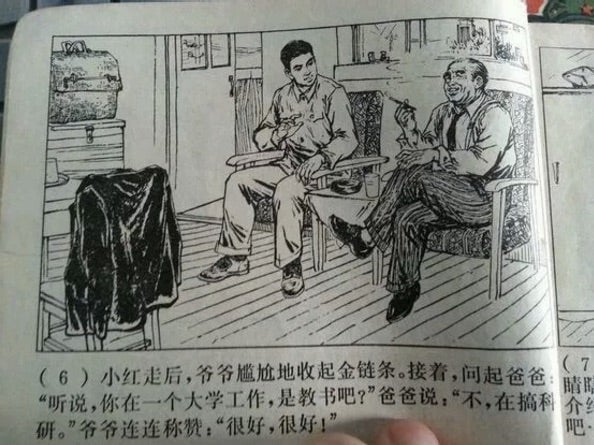

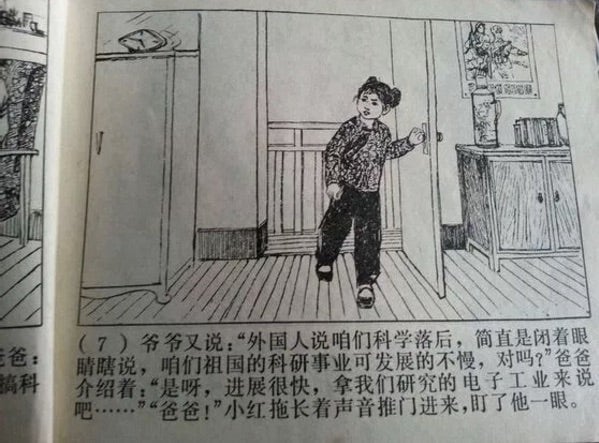

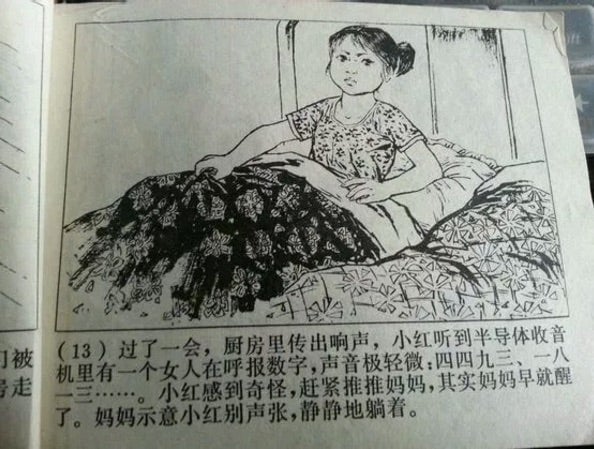

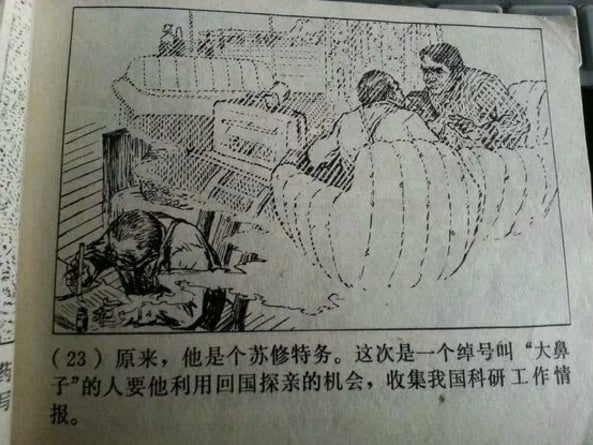

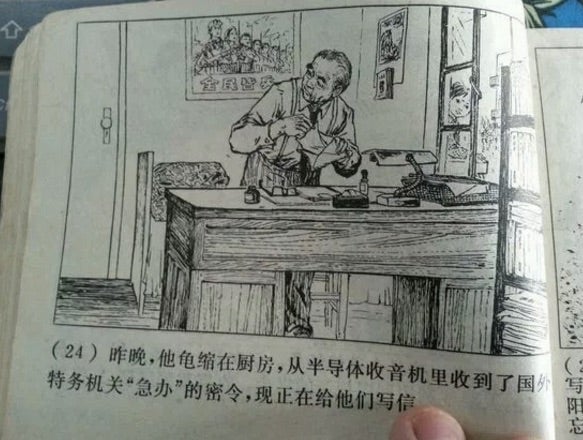

Cartoon propaganda was used to support the cause. As outlined by ChinaSmack, Xiao Hong’s Struggle Against Dear Grandpa, a comic book from the early seventies released by Shanghai Peoples’ Publishing House, tells the story of a young girl who learns her father’s uncle (referred to as “grandfather”) is actually a spy for the Soviet Union. Her suspicions first arise when she notices the man asking her father for information about his university’s research project.

Xiao Hong later catches him listening to a transistor radio overnight, which leads her to report him to authorities.

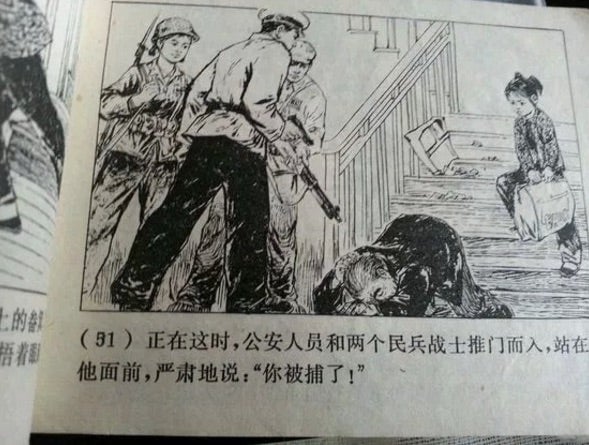

Harnessing her “revolutionary spirit,” she reports him to the police, who arrest and punish him.

Social media reaction to the most recent cartoons in China focused more on the characters’ dating than the spying. One commentator alleges the woman dating a foreigner is likely from Shanghai, a dig at city’s abundance of foreigners. Another suggested a happier ending for the story (link in Chinese)—”The Ministry of State Security should print them a marriage certificate.”