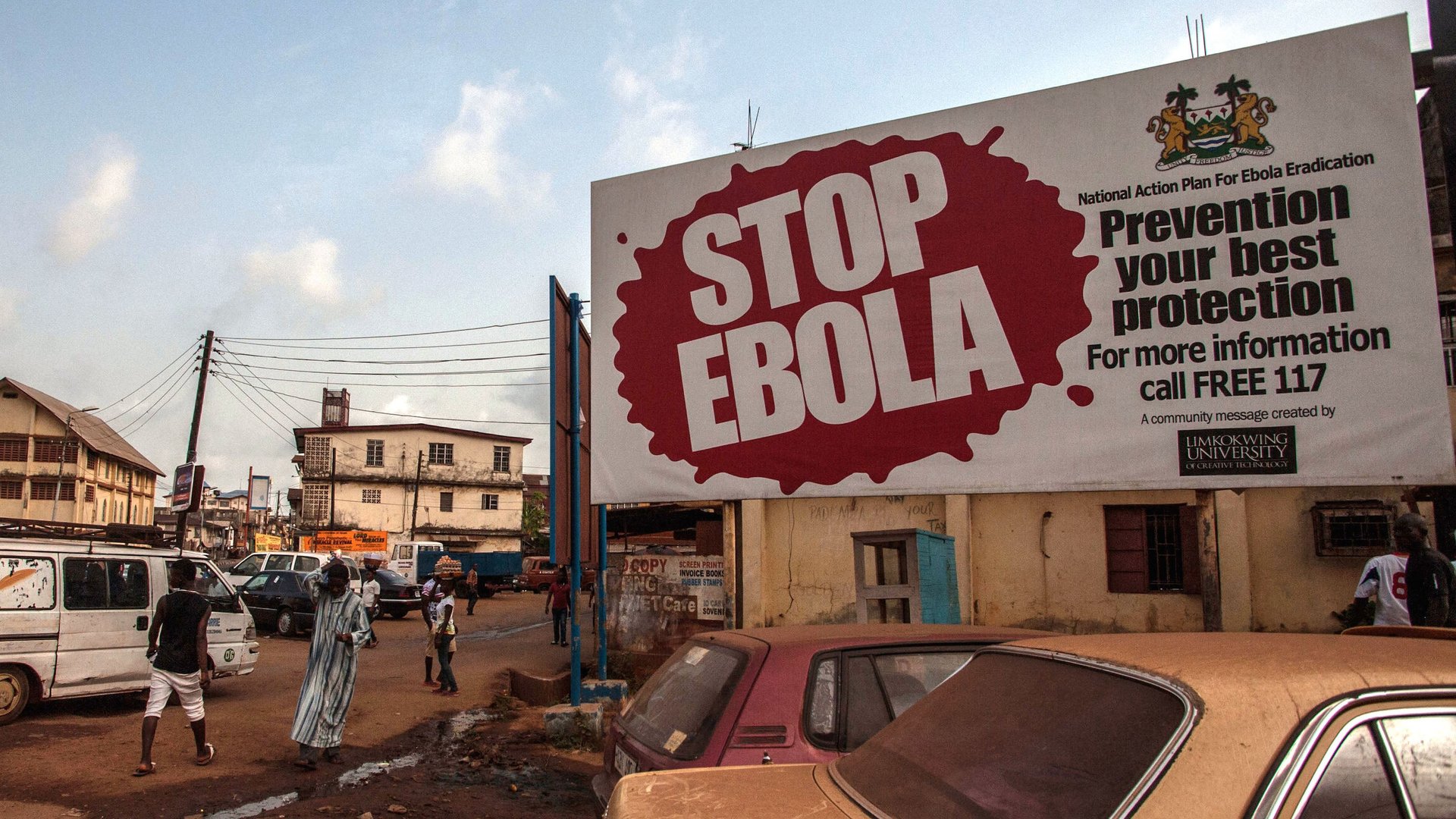

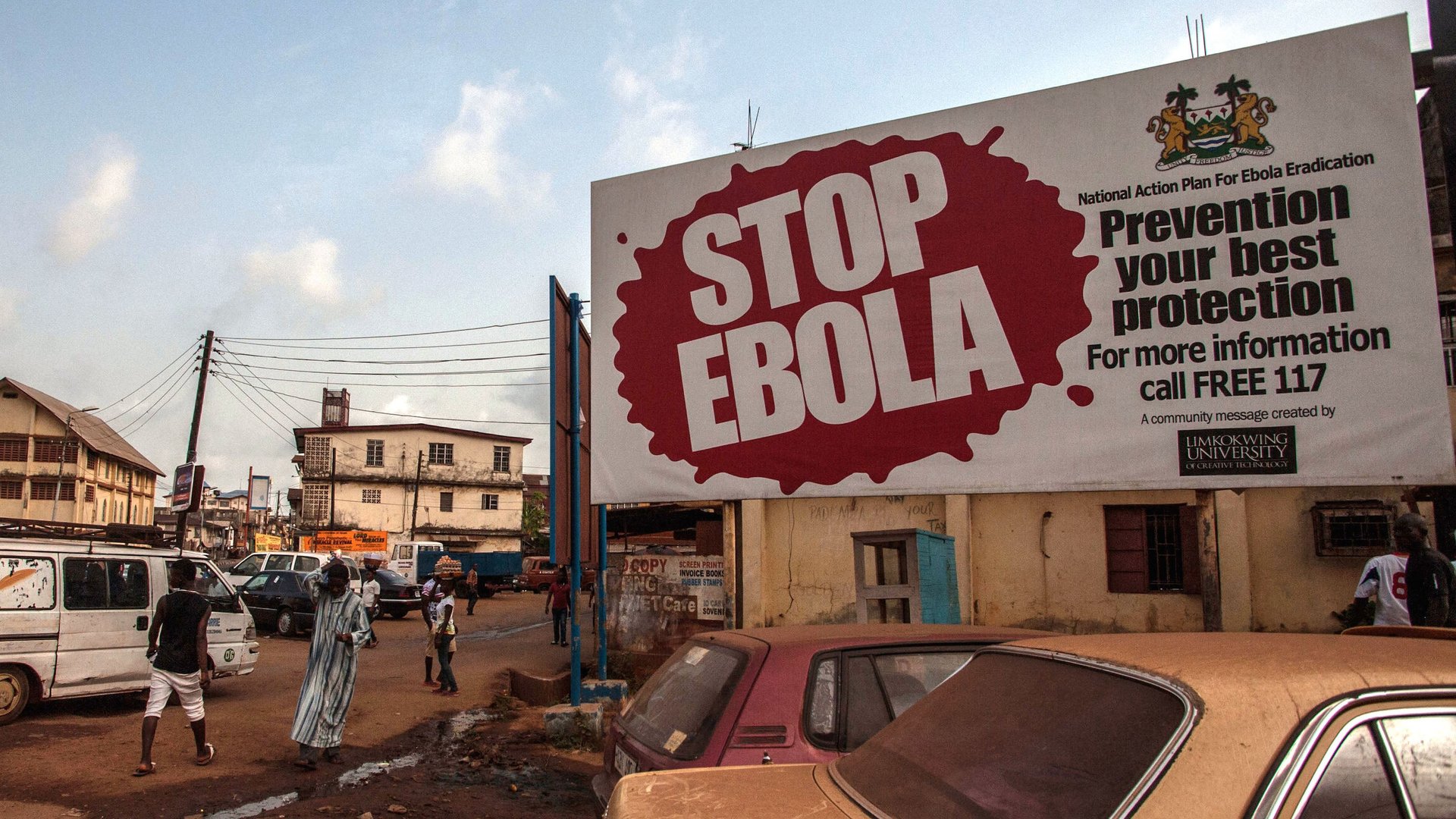

Ebola resurgences in West Africa suggest the virus can linger longer than expected

On Apr. 1, a 30-year-old woman in Liberia died of Ebola. Her death put an end to Liberia’s Ebola-free status–for the third time since the country’s outbreak was first declared over in May 2015.

On Apr. 1, a 30-year-old woman in Liberia died of Ebola. Her death put an end to Liberia’s Ebola-free status–for the third time since the country’s outbreak was first declared over in May 2015.

In 40 years of Ebola outbreaks, there has never been one as complicated as the epidemic currently smoldering in West Africa. Since December 2013, the virus has killed more than 11,000 people.

The fight to stop the deadly disease has made significant progress, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring in March that Ebola was no longer an international public health emergency. This finding was reinforced after the hardest-hit countries (Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone) were deemed free of the disease in recent months. But each of those countries have gone on to experience new cases of Ebola, starting the clock over again.

In order to understand this cycle, it helps to understand that a country must find no new cases of Ebola for 42 days in order to be declared free of the disease—twice the normal incubation period for an Ebola infection. Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone each made it past that point, only to see fresh recurrences past the 42-day mark. These repeated outbreaks have led scientists to conclude that the disease can linger in the body for much longer than previously understood.

The fact that Ebola can lurk in people’s bodies after its normal incubation period seems to be related to its apparent ability to lurk for months in hidden bodily reservoirs: fluid from the eyes, breast milk, vaginal secretions, and most notably, semen.

“There is considerable evidence that this newest chain of transmission in Guinea was from sexual transmission from a survivor,” says Dr. Daniel Bausch, an associate professor of tropical medicine at Tulane University and the WHO’s lead for epidemic clinical management in pandemic and epidemic diseases.

Previous research suggested Ebola could persist in the semen for 40 to 90 days. But that window has been eclipsed in this epidemic by a considerable amount. A probable case of sexual transmission occurred approximately six months after the patient’s initial infection last year in Liberia. Another study found evidence of Ebola in the semen of 25% of surviving men tested seven to nine months after infection. And it takes only a single transmission to kick off a fresh recurrence of the disease.

While we knew from previous epidemics that Ebola could “hide out” in some tissues well after the patient had recovered, this outbreak is showing us just how long that can be.

“The virus does seem to persist longer than we’ve ever recognized before,” Bausch confirms. “Sexual transmission still seems to be rare, but the sample size of survivors now is so much larger than we’ve ever had before (maybe 3,000-5,000 sexually active males versus 50-100 for the largest previous outbreak) that we’re picking up rare events.” If we assume that a quarter of them could still transmit Ebola via sex for a better part of a year after they became ill, that’s a lot of possible new cases.

There is at least one upside to the unprecedented nature of the outbreak. It’s allowed control teams to test new interventions, including ring vaccination, in which all people who may have come into contact with Ebola survivors receive vaccination.

“As long as we can contain secondary transmission from them [Ebola survivors], I do expect that in the not too distant future we will finally have all chains of transmission extinguished and the virus cleared in the vast majority of survivors,” Bausch says. Between these vaccination protocols and enhanced surveillance of the population—keeping a watchful eye out for any new cases in the hospitals or villages—we may finally be getting closer to the end of the largest Ebola outbreak in history.