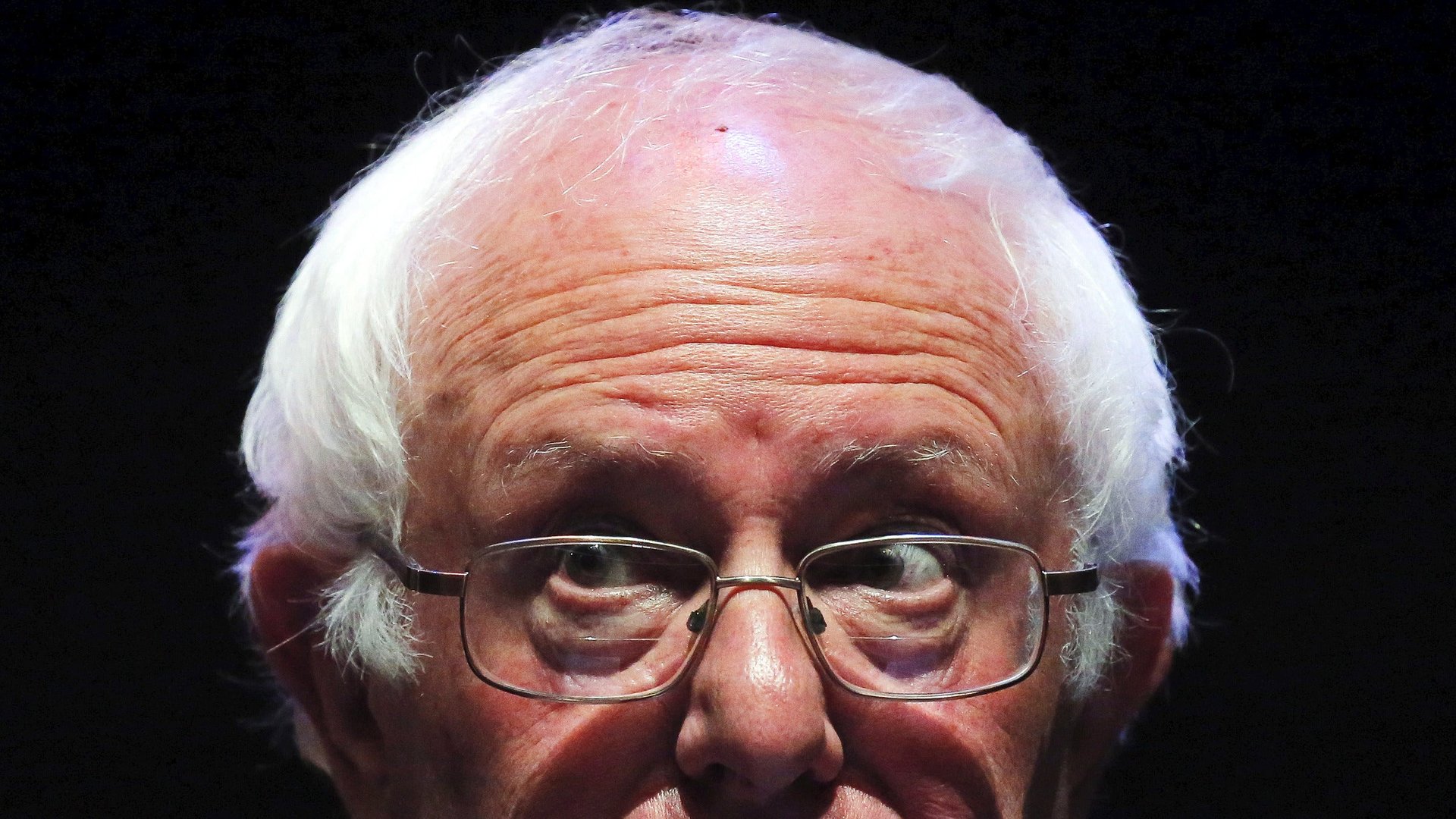

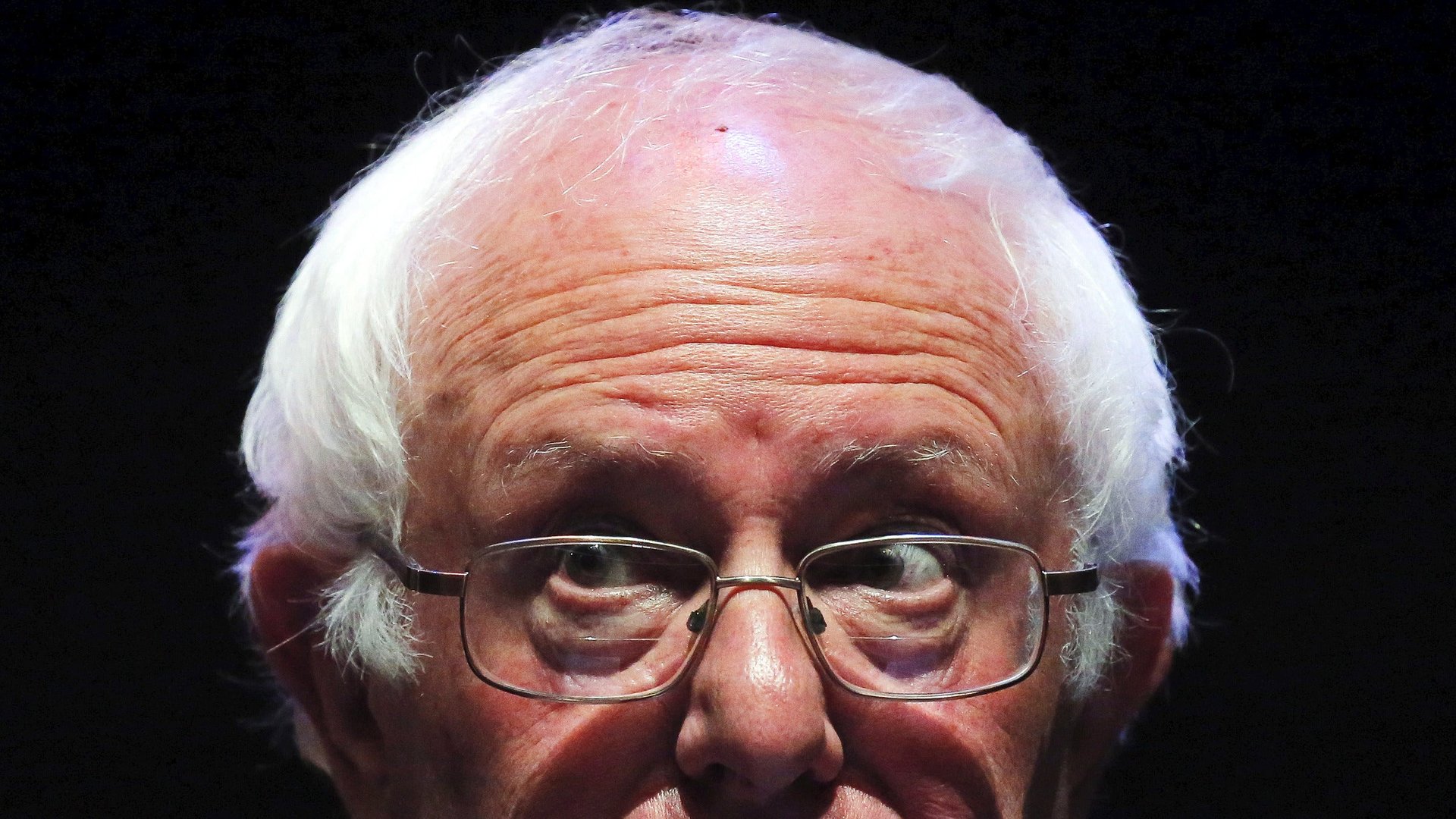

Bernie Sanders finally reveals the one tax he doesn’t want to raise

Personal income? Investments? Inheritance? Cigarettes? Marijuana? Bernie Sanders will gladly tax it all.

Personal income? Investments? Inheritance? Cigarettes? Marijuana? Bernie Sanders will gladly tax it all.

But keep your government hands off his Coca Cola.

Campaigning in Pennsylvania this week ahead of the state’s Democratic primary on April 26, Sanders drew a hard line against a soda tax proposed by Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney to fund universal pre-kindergarten education for the city’s children.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is backed by Kenney, and backs his soda tax in turn.

“I do not support paying for this proposal through a regressive tax on soda and juice drinks that will significantly increase taxes on low-income and middle class Americans,” Sanders said in a statement. “At a time of massive income and wealth inequality, it should be the people on top who see an increase in their taxes, not low-income and working people.”

That’s a bit of a surprise, given that Sanders’ own tax plan raises taxes on the income of the poor and lower middle-class Americans by 22% and 15% respectively—a much more significant and harder to avoid increase than 3 cents per ounce of soda ($0.60 for a 20 oz. bottle of soda).

Sanders defends his across-the-board increases by pointing out that low-income people would benefit because they would no longer pay insurance premiums, among other new services. But Kenney could also argue that his constituents will benefit from increased access to childcare, and potentially lower health care costs as well.

“I’m disappointed Sen. Sanders would ignore the interests of thousands of low-income—predominately minority children—and side with greedy beverage corporations who have spent millions in advertising for decades to target low income minority communities,” Kenney told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

“Sin taxes” on products like soda, plastic bags, tobacco, and alcohol attempt to reduce the negative externalities on goods that are legal but not consequence-free. They do tend to be regressive—falling more often on low-income people—because poorer Americans spend a greater share of their income on consumer goods.

But that is part of the point, since the taxes are designed to reduce usage as much as they are to raise revenue. In the US, poor Americans are significantly more prone to obesity and the health problems that go along with it, incurring costs which are often passed on to taxpayers through Medicaid and Medicare. Sanders himself has supported increases in the equally regressive tax on cigarettes, which works on similar logic.

But despite popularity among local governments and public health experts, soda taxes aren’t overwhelmingly popular with voters. You may remember the blow-up over then-New York mayor Michael Bloomberg’s proposed a ban on the largest soft-drink sizes. In 2014, 55% of San Francisco voters backed a soda tax referendum, but it failed for lack of the required 2/3 majority to pass.

Sanders is in the fight of his political life, and Pennsylvania is the biggest prize in next week’s election. Clinton is leading in public opinion polls, and is expected to do well in heavily-African American urban Philadelphia. Sanders seems to be hoping that he can leverage dislike of the tax to boost his presidential campaign, though a poll commissioned by Kenney last fall suggests that 57% of his constituents back the tax.

But it’s a funny look, all the same, to see Sanders to the right of politicians like Clinton and Bloomberg.