How Shakespeare’s words helped unlock a sexual awakening, 400 years after his death

Jillian Keenan looks the way a Jillian should look. With her straight brown hair, green-blue eyes and welcoming smile, you could easily sit across from her on the subway and never know that she’s been hiding something her whole life.

Jillian Keenan looks the way a Jillian should look. With her straight brown hair, green-blue eyes and welcoming smile, you could easily sit across from her on the subway and never know that she’s been hiding something her whole life.

Whack.

A leather strap slaps down onto the couch’s armchair. It cuts through the air clean. In her tiny Hell’s Kitchen apartment, Keenan, 29, is showing me how she likes to get spanked.

Did I mention that fetishists hide in plain sight?

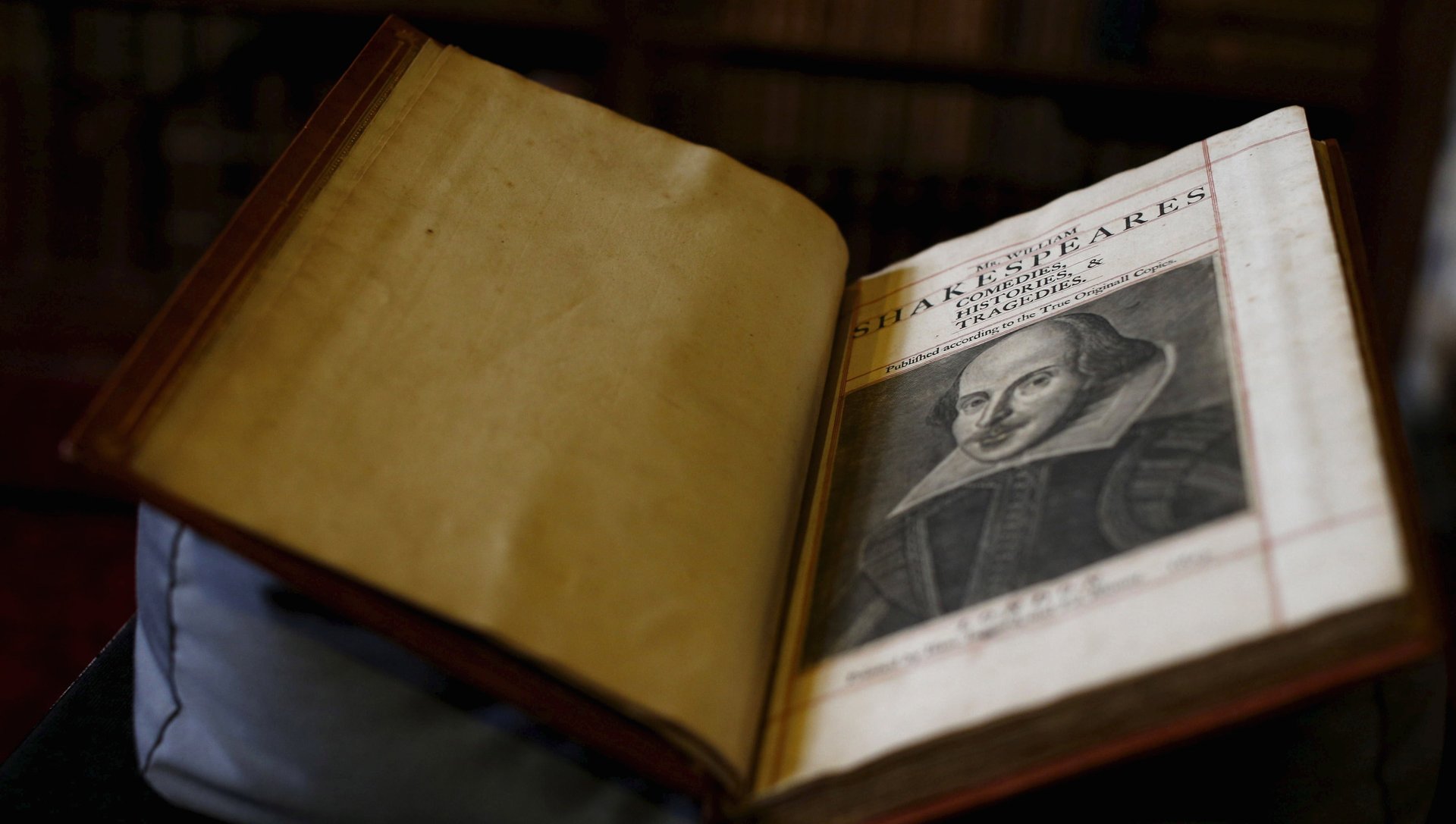

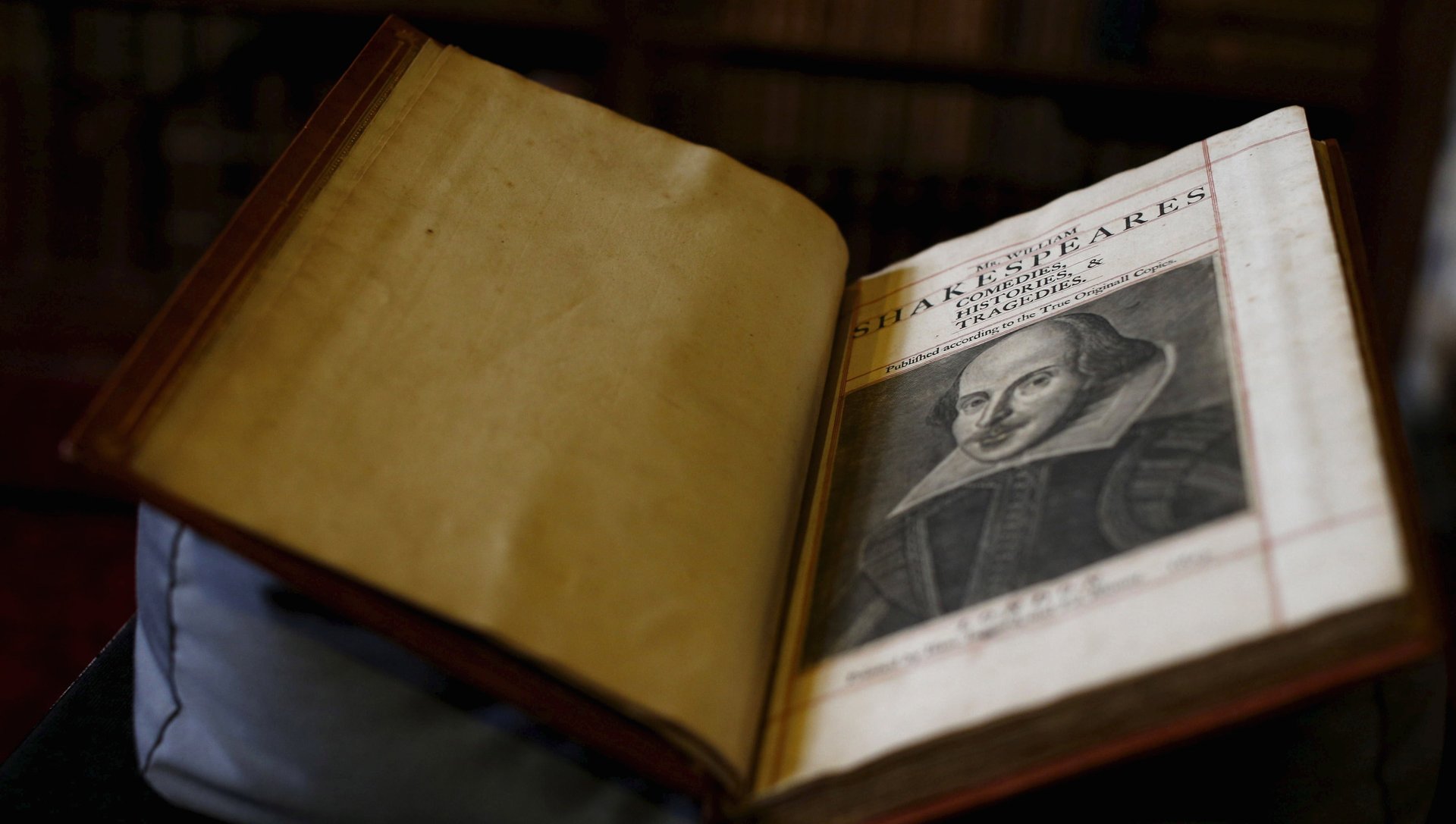

Sex with Shakespeare, Keenan’s first memoir, was published on April 23rd—the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Using Shakespeare’s plays as a vehicle, Keenan explores her sexual identity as a feminist masochist. Whether it’s to do with love or fear, pleasure or pain, Keenan relates her struggles seamlessly to the ones faced by some of the Bard’s most famous characters. This book is her journey to self-acceptance.

Each of the book’s 14 chapters contains five acts and is named after a Shakespeare play. Keenan’s writing is honest as a diary, provocative as a dirty magazine, and seamlessly blends literary criticism with elements of magical realism.

In times of need, these characters appear to guide her: Helena from A Midsummer’s Night Dream finds her wandering the Oman desert alone at night; Friar Lawrence from Romeo and Juliet appears in a Genevan airport bathroom; Lady Macbeth from Macbeth joins her at an oyster and wine bar in the Financial District.

To be clear, Keenan’s spanking fetish isn’t an occasional kink or an accessory to sex. Her fetish–in her own words–is unchosen, innate, and lifelong. It is a part of her that she finds, at least initially, terrifying.

Along the way, we are given a window into Keenan’s tumultuous childhood, a period dominated by an unstable mother who would sometimes spank her as punishment. The memory of her mother spanking her in a middle school public parking lot has haunted her for two decades, and Keenan’s commentary on consent and parenting is essential to her story. “The difference between being spanked consensually and non-consensually is in my mind the same thing as having sex consensually and having sex non-consensually,” she said. Keenan views spanking as a sexually charged act.

Even as a child, Keenan could tell there was something different about her fascination with strict mother characters. Unable to parse through the psychological implications, Keenan’s adolescent mind wandered to places she could not control. Like Caliban from The Tempest, Keenan felt powerless, confused, trapped within the confinements of her sexuality. “I longed to uncage myself,” she writes, “I longed for Caliban’s ugly honesty and the unself-consciousness of his impulses.”

Pop culture offered little relief when it came to healthy depictions of non-traditional sexuality; neither did French cinema. Even today, “Fetishes are a conversation we are not having in this country,” she says. For 26 years, she kept hers a secret. But like many of Shakespeare’s plays, the truth almost always finds a way to the surface.

Traveling across the world in search of answers, from Oman and Spain to Singapore and Somalia, Keenan meets a diverse set of characters with stories as fascinating as her own. In this new community she finds new friends and new romances—but most importantly, she finds herself.

Today, Keenan works as a foreign correspondent. Her New York City apartment walls are painted yellow and green and decorated with mismatched wall frames. Her ceiling is laced with fairy lights. She sits cross-legged with her book in hand. She’s at peace.

No longer worried about keeping her secret hidden, Keenan is proud to put her name on a book that openly outs her sexual proclivities.

“I felt unnatural for so long,” she says, uncrossing her legs. “But Shakespeare is the single greatest narrator for human nature. Everybody’s in Shakespeare, so finding parts of me in Shakespeare made me feel like I was going to be okay.”