An electric car talent shortage is making for a frenzied hiring spree

You are watching a generational free-for-all—one of those bare-knuckles, international brawls that can end up determining the winner in transformative new commercial spaces. Last time, it was smart phones (for those who have been living under a rock, Apple won); before that, it was portable music (again, Apple).

You are watching a generational free-for-all—one of those bare-knuckles, international brawls that can end up determining the winner in transformative new commercial spaces. Last time, it was smart phones (for those who have been living under a rock, Apple won); before that, it was portable music (again, Apple).

Now, it’s cars. But typically, the adversaries—by and large American, Chinese, German and Japanese—are debating what the future looks like: Are we on the cusp of an age of autonomous cars, shared cars, or electric cars? Is it none, or all three?

If you are Ford, the future—at least for electric cars—is coming only slowly, and is nothing to get in a lather over. Tesla, Apple, and a knot of Chinese financiers seem to see just the opposite: They are furiously grabbing each other’s talent in the hopes of ushering us all toward a rapidly developing electric, autonomous-driving boom.

The answer is important—automobiles are a $1.7 trillion global industry, and directly employ 5 million people in the US and Germany alone. A serious shakeup in the auto market would reverberate much the way that oil’s turbulence has roiled the global economy.

In one example, BMW confirms to Quartz that its core electric development team has left the German company lock, stock, and barrel. Its destination is Future Mobility, a Chinese startup partly owned by Foxconn, The Wall Street Journal first reported. Foxconn is pivoting away from being the mere assembler of iPhones and has bought control of the Japanese electronic giant Sharp, now one of the world’s leading electric car teams, stripping assets from two of the largest industrial economies with plans to break into a third—the US.

Meanwhile, Jia Yueting, CEO of Chinese electronics maker LeEco, has doubled down on a big bet on electric automobiles by unveiling the LeSee (pictured above) in Beijing. Yueting is also a major investor in two big electric startups in California—Atieva and Faraday Futures. Faraday has just broken ground on a gigantic factory in Nevada, and, in another example of the race for talent, hired a former senior Tesla executive—Dag Reckhorn, who oversaw the manufacturing side of the Model S until 2013—to run it.

This Chinese fervor coincides with that around Tesla, which has amassed almost 400,000 pre-orders for its mainstream electric Model 3 at least 18 months ahead of its availability for delivery. Apple, meanwhile, continues to hire Tesla employees for the development of its semi-secretive electric Titan.

“Talent and experience with advanced technology including vehicle electrification is scarce and highly valued,” said Tony Posawatz, a former senior executive at General Motors.

But the technologies may be moving on separate tracks

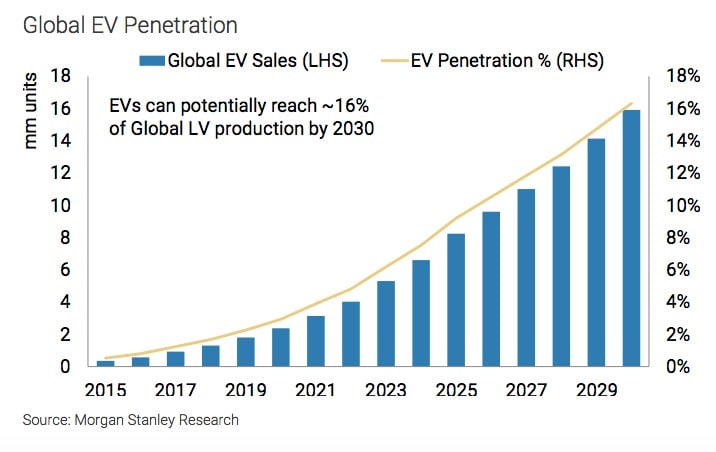

In an April 19 note to clients, Morgan Stanley’s Adam Jonas forecast a robust future for shared electric cars. International forecasting agencies and major oil companies generally forecast that over the next quarter-century, pure electric cars will capture only a few small percentage points of annual sales, but Jonas predicts that by 2030, electrics will have 16% of the annual global market (see chart above).

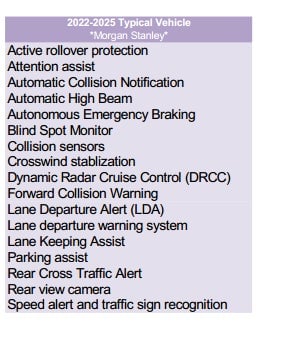

Jonas predicts a separate, faster track for self-driving functionality (see chart, left): he says that by 2025, the typical new car will be filled with autonomous functions as standard equipment. According to BMW, Jonas by and large has it right—new BMWs will have most of these features by 2025, a spokeswoman said.

GM and Ford did not respond to a query seeking comment. But here again one finds a divide: Ford is on record as moving aggressively toward a self-driving car. GM, conversely, has made a substantial, $500 million investment in Lyft, the Uber rival, and designed its coming mainstream electric Bolt with ride-sharing in mind, but thinks self-driving cars are coming much more slowly.

Since no one can possibly know what consumers will embrace and how fast, it seems rational that bets are all over the table. But this also suggests a prolonged period of anxiety, from global automobiles to the big technology companies of Silicon Valley.