The restorative techniques that frontline war zone workers use to minimize stress

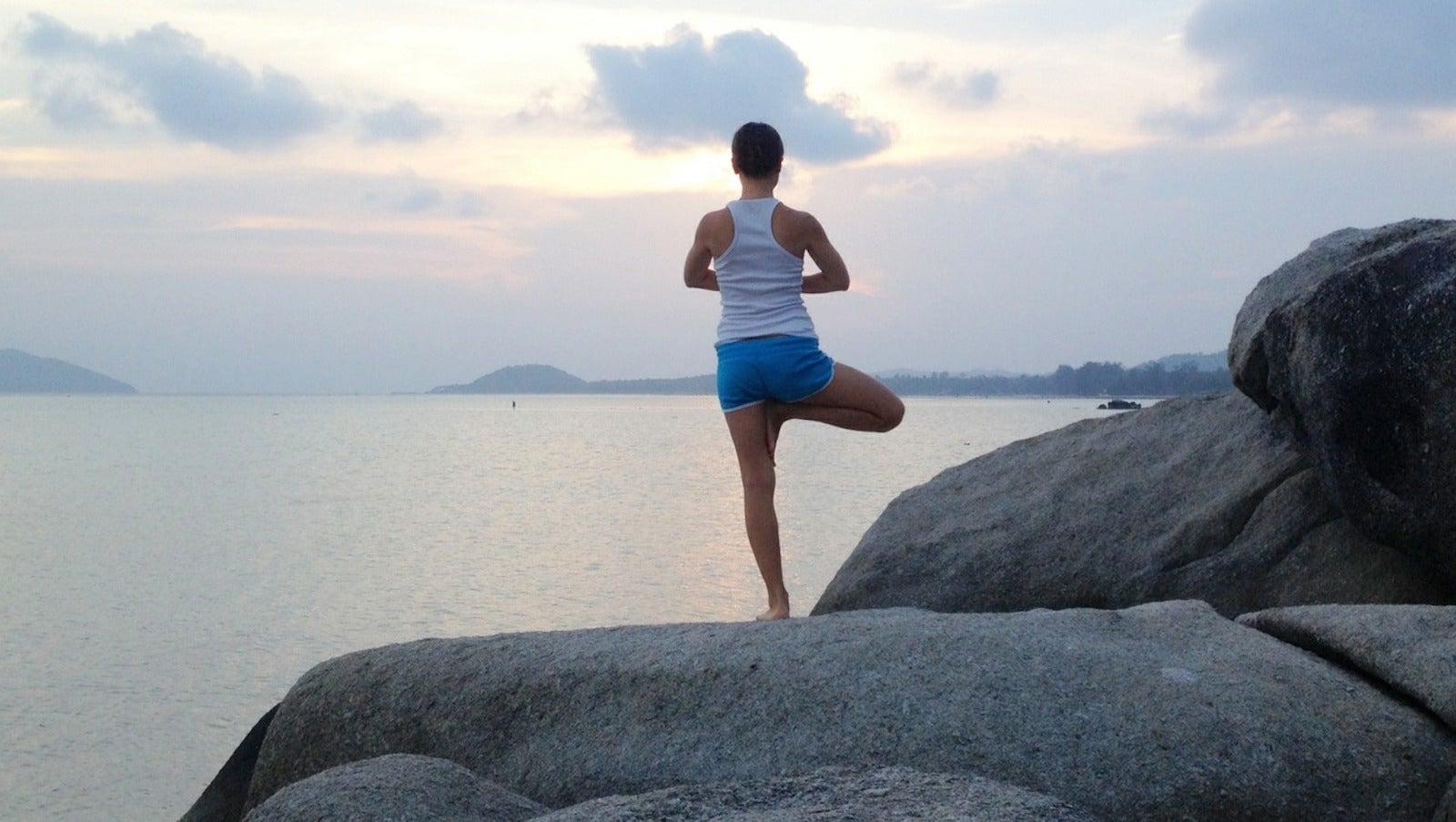

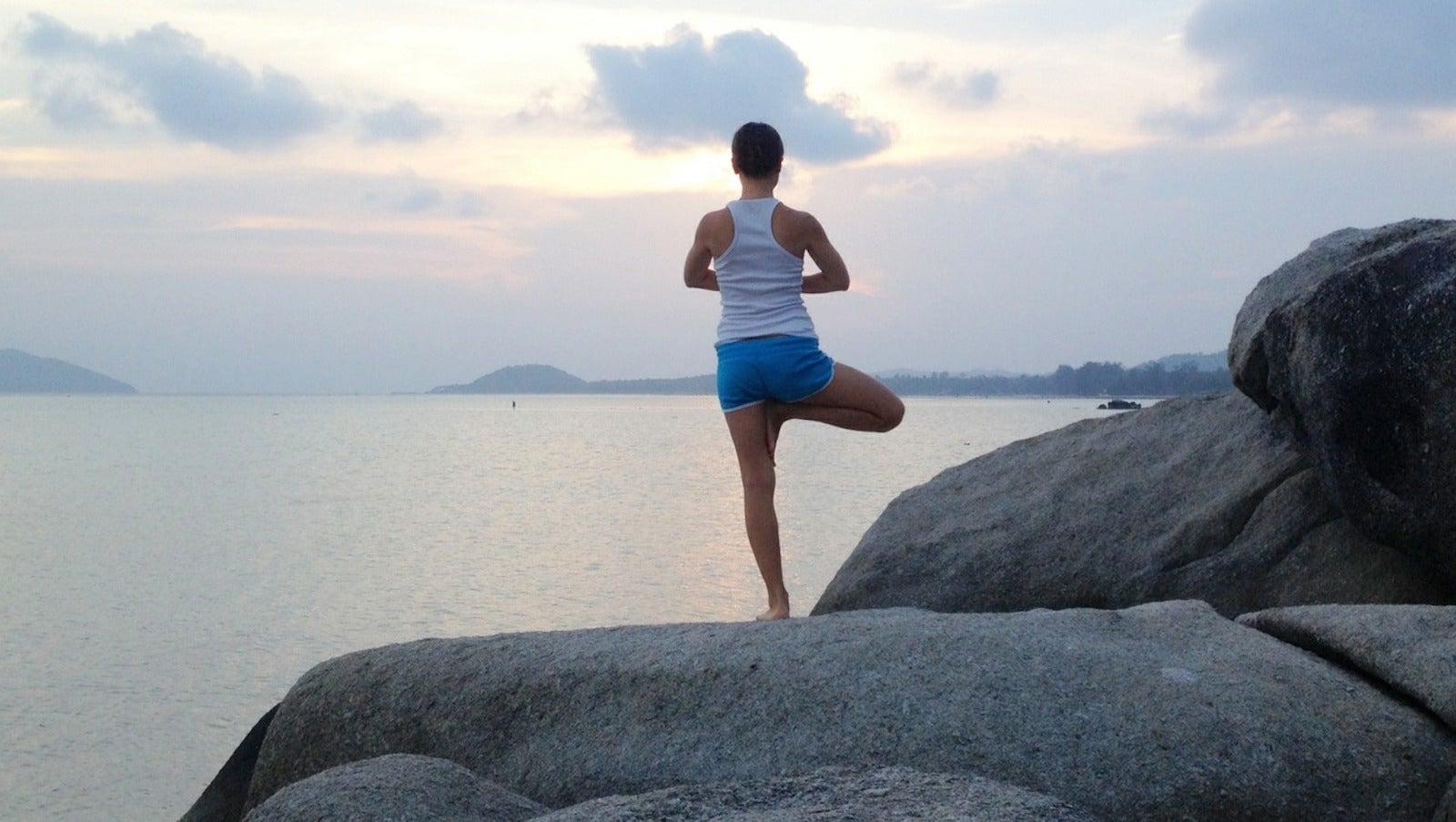

Violence was in the air in Kosovo in 2003, when Minna Jarvenpaa started practicing yoga.

Violence was in the air in Kosovo in 2003, when Minna Jarvenpaa started practicing yoga.

Stationed in the ethnically divided Balkan nation with a UN peace mission, Jarvenpaa was the acting mayor of a town called Mitrovica, home to opposing factions of Serbs and Albanians. “I could tell violence was about to break out,” she says.

As her stress accumulated, Jarvenpaa began to develop insomnia. One day, a friend took her to a yoga class in town. “For the first time in weeks,” she recalled, “I could feel my body relaxing.” She continued practicing yoga when she was relocated to Afghanistan, and found that it helped her deal with living in a country at war.

Now, Jarvenpaa is sharing her discovery with other aid workers, diplomats, and journalists whose nerves have been jangled by working in war zones. Her organization, Tools for Peace, offers restorative retreats in the Italian countryside, with workshops tailored to these frontline workers, run by yoga teachers and psychotherapists.

Like soldiers, many diplomats and aid workers suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after postings where they experience violence or live in fear. “Both their bodies and minds are really unhealthy when we begin,” says Helen Cushing, who will teach yoga at the retreat. Cushing goes by her Sanskrit name, Ahimsa, and has taught therapeutic yoga to military veterans in Australia for over a decade.

The retreat will be open to anyone who suffers from anxiety or stress, whether they have worked in a war zone or not. “There’s no difference whether you are stressed out from seeing war or you have other reasons for stress and trauma in your life,” Jarvenpaa says. “The yoga is the same.”

The exercises Ahimsa teaches are about refocusing the senses inward in order to escape from the hyper-vigilant thought patterns of PTSD—but they can be useful to those of us dealing with normal daily anxiety, too.

Breathe like a humming bee

The veterans who come to Ahimsa with PTSD often manifest the condition in unhealthy breathing patterns. “The breath is key,” she explains.

The first thing she teaches her students is how to breathe deeply, so that their stomachs expand, instead of their chests. Fast breathing activates the fight-or-flight response—associated with the hyper-vigilance characteristic of PTSD—and, according to Ahimsa, slow, deep breaths can override that. This type of breath can reset your nervous system, she says.

The simplest type of breathing to practice for stress management is something Ahimsa calls “humming bee breath.” To do it, simply put your fingers in your ears and hum as long as you can, then repeat.

Chill without Netflix

In addition to teaching her students to retrain their breathing, Ahimsa teaches them to practice intentional, deep relaxation. She guides her students through the process of letting go with a technique called yoga nidra. It takes between 15 and 30 minutes and is done lying down. During the process, she uses her voice to guide her students through a number of mental exercises, which include bringing awareness to each part of the body and awareness to the breath. She also uses visualizations of nature to help her students relax.

Ahimsa gives her students recordings of her voice to use at home, but apps that perform the same function are available. She recommends this one.

Successful deep relaxation results in a sleep-like state, where you remain semi-consciousness but your body is essentially asleep. Ahimsa says that many of her students who suffer from insomnia use the recording to fall asleep at night, instead of watching TV or reading.

Open up to a stranger

The retreat also offers group therapy sessions, guided by psychotherapist Martin Dietrich and his partner Diana Ivanova. “Usually when people do yoga there is no sharing,” Ivanova says. “I found it’s quite important to bring this aspect in.”

Ahimsa agrees. She invites the veterans to stay and chat at the end of her classes. “We have a cup of tea,” she says. “That social aspect is crucial as well.”

Ivanova says talking to a group of strangers about yourself can be particularly helpful, as you are often able to open up more to strangers. “The group becomes a mirror,” she says. “What you say to people you don’t know can teach you a lot about yourself.” Her sessions tend to be very open and unguided. “It’s about sharing, creating a safe place, and not emphasizing the medical condition,” she says.

For the rest of us, local interest-based meetups, therapy groups, or support groups can offer similar opportunities to open up to a group of strangers and learn more about yourself. Mental Health America keeps a directory of groups for people suffering from anything from attention deficit disorder to anxiety caused by debt, and Psychology Today offers a searchable database of therapy groups as well.

Build a toolbox

Tools for Peace offers its participants just that—tools—and its organizers emphasize that some will work better for an individual than others.

“It’s quite interesting how things combine,” Ivanova says. “For some people, the yoga will be very powerful, and for others it will be very powerful to talk to others.”

Whether your body or your mind responds most, both will benefit, according to Ahimsa. “In yoga, it’s regarded that the body and the mind work together,” she says. “We’re giving people a tool kit that works with both, so that they can find what works best for them.”

For more tips from Ahimsa, check out her book here and a documentary about her work at www.lifebeyondtrauma.com.