Italy’s failure to form a government doesn’t bode well for the euro

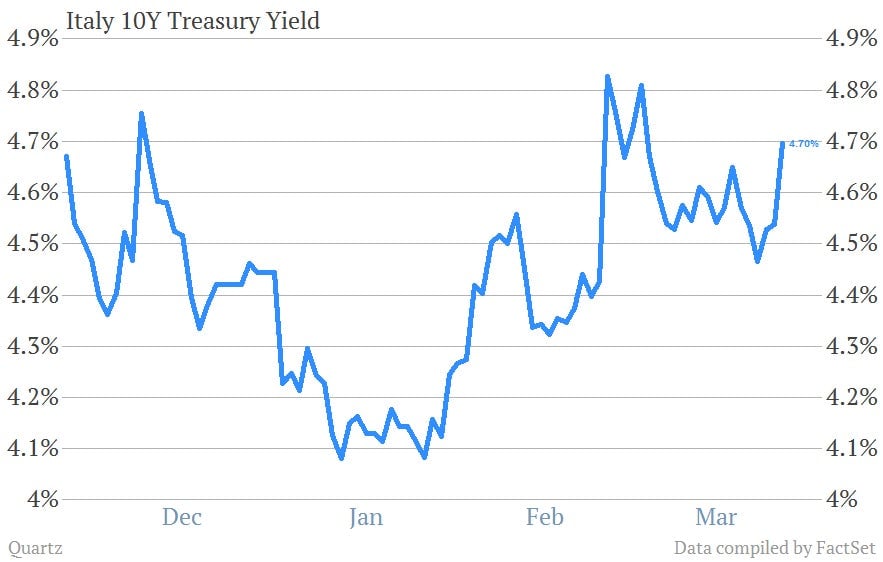

“Only an insane person would want to govern this country, which is in a mess and faces a difficult year ahead,” said Pier Luigi Bersani today, throwing up his hands. That—along with continuing concerns about Cyprus, where banks will open tomorrow after nearly two weeks of shutdown—frightened the markets. Yields on Italian bonds rose 16 basis points. And with good reason.

“Only an insane person would want to govern this country, which is in a mess and faces a difficult year ahead,” said Pier Luigi Bersani today, throwing up his hands. That—along with continuing concerns about Cyprus, where banks will open tomorrow after nearly two weeks of shutdown—frightened the markets. Yields on Italian bonds rose 16 basis points. And with good reason.

Bersani has been trying and failing to assemble enough votes in the Italian Senate to form a coalition government. Even with the support of former PM Mario Monti and his followers, Bersani still needs 15-17 more seats for a majority, according to Wolfango Piccoli, a political analyst at the Eurasia Group. Bersani has refused to get into bed with the center-right party led by Silvio Berlusconi. But he has also failed to win over the anti-establishment upstart Five Star Movement led by Beppe Grillo.

That means new elections are probably inevitable—if not later this year, then in 2014. That could be bad for markets and for mainstream political parties. Grillo, who wants to hold a referendum on the euro, could easily gain more support if Italians go back to the polls.

The main question, then, is when. Piccoli wrote in a note to clients that Italy’s outgoing president, Giorgio Napolitano, will try to delay an election:

Neither the president nor the mainstream parties favor elections over the near term, meaning that a fixed-term cabinet supported by a broad coalition of political forces and led by a low-profile prime minister is the most likely outcome if Bersani fails.

The task of choosing that cabinet will fall to Napolitano. Bersani’s party will likely try to get by for as long as it can with a minority government. But even if Bersani can hang onto tenuous control, Italy will probably be unwilling to adopt new reforms.

This stubbornness could jeopardize its place in the euro. Fear about the fate of peripheral euro area states is already unsettling European markets. If it suddenly faces more difficulty borrowing money, the Italian government would need a lifeline from the European Central Bank (ECB) to avoid default—the central bank has promised to purchase government bonds as part of its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program. But if Italy refuses to accept more austerity, then the ECB may not come to its aid in a crisis. In this case, either Europe would have to lighten up, or Italy would exit the euro.

Lombard Street Research’s Charles Dumas argues that this political turmoil—in particular, votes for the sleazy Berlusconi and wildcard Grillo—is simply a sign of the times:

Those votes simply reflect the difficulty of getting continental politicians to tell the truth—that the euro has failed, and the austerity its distortions have bequeathed is also failing. There is no chance that debt problems in Italy, such as might trigger a request to the ECB for OMT support, would make further austerity acceptable to the Italian parliament.

Europhiles should pray he’s wrong. European leaders may grumble about it, but they probably don’t want to sacrifice their third-largest economy. Then again, Bersani’s outburst today was the most truthful thing an Italian politician has said recently.