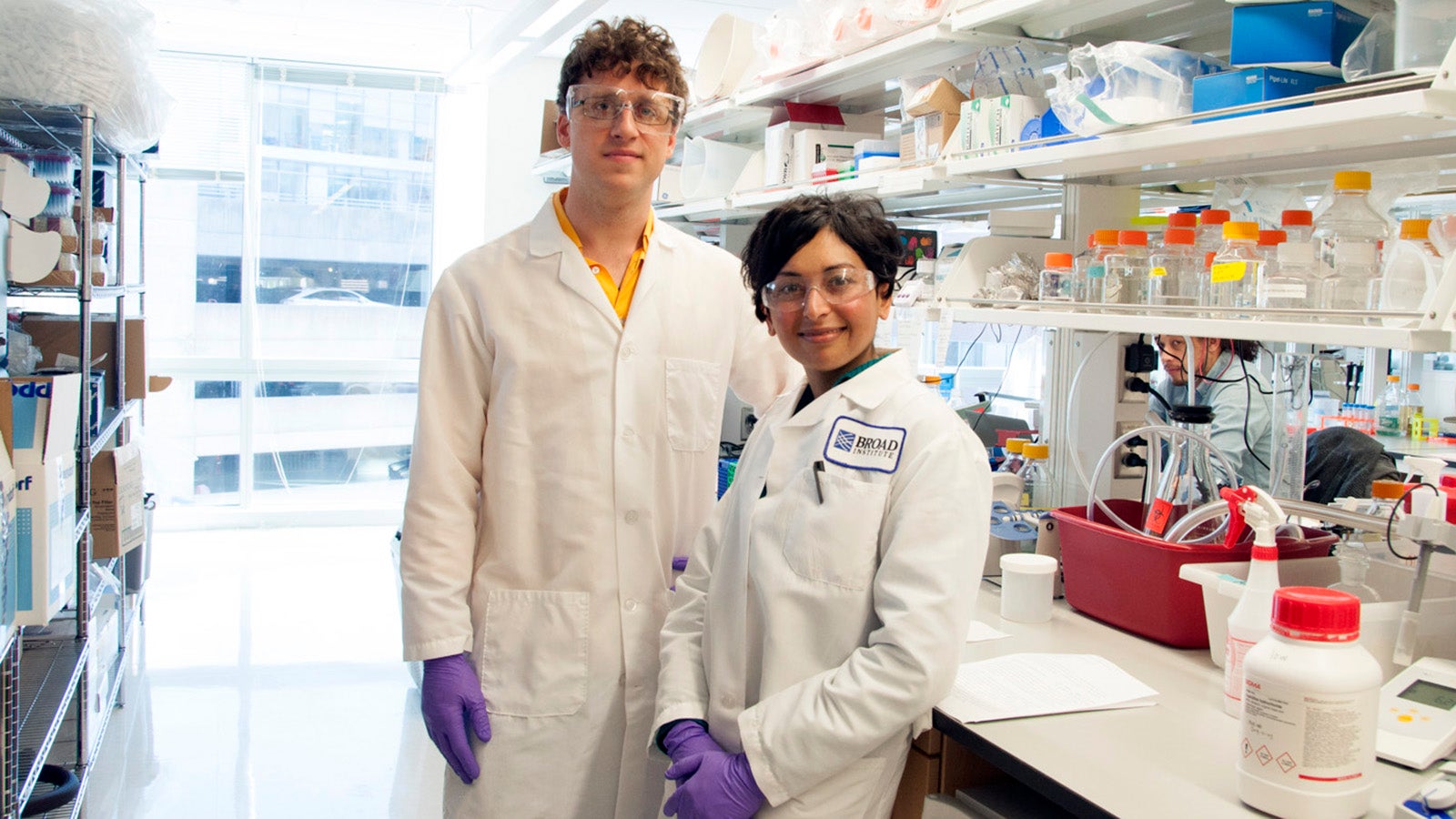

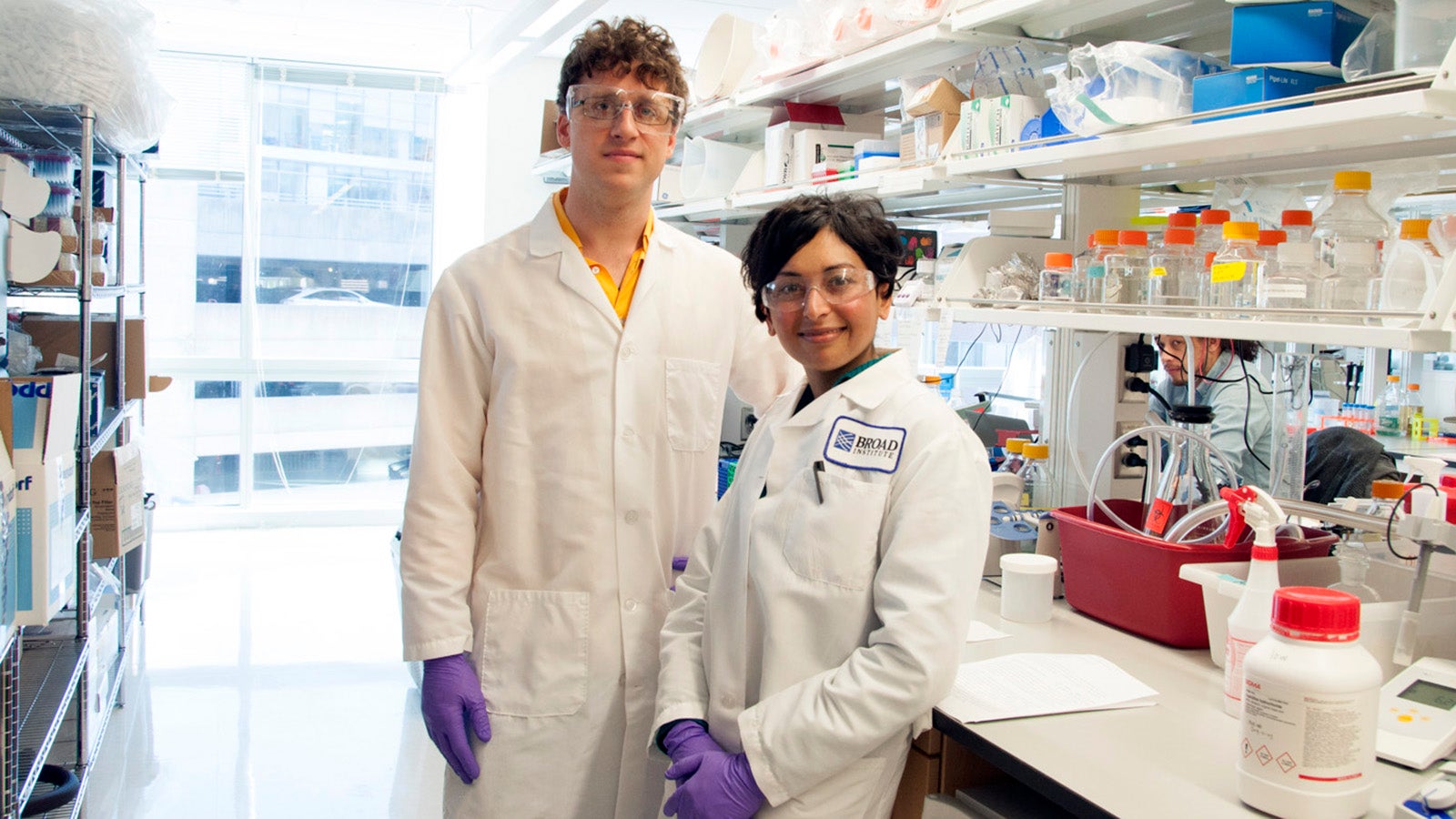

This couple gave up their careers to train as scientists and find a cure for her rare genetic disease

When Sonia Vallabh’s mother died of a rare disease at the age of 52, she found out that she was carrying the same ill-fated genes. Soon after her diagnosis was confirmed, she and her husband, Eric Minikel, set out on a quest to find a cure.

When Sonia Vallabh’s mother died of a rare disease at the age of 52, she found out that she was carrying the same ill-fated genes. Soon after her diagnosis was confirmed, she and her husband, Eric Minikel, set out on a quest to find a cure.

Sonia is 32 and her inherited genetic condition, called fatal familial insomnia, usually strikes people in their 50s. It is caused by the abnormal shape of a protein that causes other healthy proteins to become abnormal too. These mutant proteins, called prions, collect in the brain and cause severe insomnia leading to death.

Through perseverance and determination, and without any scientific training (he was an urban planner and she was a lawyer), today the couple are enrolled in a biology PhD program at Harvard University researching a cure for Sonia’s disease. To talk about their experience, they took to Reddit to answer questions from the public. We have collected some of their responses below.

How did you react to the diagnosis? When did you both decide to do a PhD?

Sonia: For us, the absolute worst time was learning that my mom’s disease was genetic (which we learned from her autopsy, after she passed away) and that I was at 50/50 risk of having inherited her disease mutation. Since prion diseases aren’t usually genetic and there was no family history prior to my mom, this came as a shock to us. The limbo of waiting for the genetic test result was the hardest time for us. The 50/50 wreaked havoc with my mind—it was like I had no place to rest mentally. I just kept turning it over and over. Although of course the result of the test wasn’t what we’d hoped for, once we had it in hand we could being to adapt to it, do our grieving and figure out how we were going to cope. It became a fact of life.

As for deciding to do our PhDs, there wasn’t a moment where we looked at each other and said, “That’s it, we have to go out and cure this thing!” It happened step by step, with the goals changing along the way. Our first goal was to become savvy consumers of scientific information so that we could advocate for ourselves as patients. Then as we learned more, our ambitions grew. I realized when I took my first job in a research lab that this wasn’t just a sabbatical from my normal life—this was a new life. But even from here, deciding to do our PhDs and focus our lives on developing treatments for prion disease was a process. I think first we had to learn enough about the specifics of the prion field to realize that there were things we could do at the bench, in the time we have (or hope we have) that could make a difference.

How do you plan on staying objective throughout testing and results if it’s your (or your wife’s) life on the line?

When it comes to objectivity, our goal fuels our discipline. We don’t think of this as a conflict at all—we have the most to gain by being true to what the science tells us.

What’s the most difficult thing about working as a husband and wife research team?

Eric: I just turned to Sonia and asked, “Is anything difficult about it?” I love it actually. Sonia is the bomb. I feel so incredibly lucky to get to spend all day every day with her. It is one of the upsides of all of this happening to us, that we get to spend almost all of our time together.

Sonia: I have gotten to see so many new aspects of Eric through this process, and to be impressed with him in whole new ways. It is impossible to feel sorry for myself for one second when I look at the beautiful human being I am getting to spend my life with.

Research is a slow thing. Realistically speaking, what is the best scenario you guys are aiming for?

The real race is to get it into clinical trials. Experimental therapies save lives, even in Phase 1. While compassionate use is one option, we would be keen to enroll Sonia in the actual trial.

How optimistic are you?

Sonia: When we were first wading into the science, we were drawn to the low-hanging fruit—studies looking at repurposed drugs, supplements, lifestyle changes. We thought we would have to draw optimism from things that could happen fast, or that we could change right away.

After 4.5 years coming to understand the field, we have such a different perspective. We’ve stopped paying attention to things that are being studied for hundreds of different diseases and used in dozens of clinical trials. We’ve started taking our cures from the specifics of our exact disease: our gene, our protein. I don’t think there’s an off-the-shelf solution for prion disease, or anything available today that influences disease.

But I’m more optimistic than ever, because I think we’re aiming right at the heart of our problem, in a rigorous way. It will take time to develop therapeutics that will work, but I feel confident that we’re working on approaches that will move the ball forward for patients. The big variable is the timeline, and the honest answer is that we don’t know if this will all move on a timeline that’s relevant to me. Day to day, I don’t think about this much. I tend to operate on the assumption that we have some time, because it’s as good an assumption as any and it’s the one that allows me to be most productive.

How can others help?

We need patients to participate in research, doctors to collect cerebrospinal fluid so we can look for biomarkers, scientists to train us and mentor us in all sorts of techniques, pharma companies to take an interest in our disease, regulators to think seriously about how to make it easier for drugs to be approved for rare fatal conditions, funders to fund us, and people to continue to show us love and support.

Vote. We need more science funding and sound science policy. Blog. The internet is awesome and is how we should be communicating science. I love when I google something and find an answer because someone else has struggled with the same question and then blogged it once they figured it out. Share. Sharing our personal stories makes us all less alone, more empowered together. Care. When your loved one gets news like the news we got, tell them what our friend Stevie told us—science has answers for you.