Stephen King’s “The Shining” is now a genre-redefining opera

To most people, opera is spear-wielding women in helmets, or maybe hefty people over-emoting in Italian. Not a plaid-clad recovering alcoholic writer’s descent into homicidal madness at a snowbound hotel in the Rockies. But with this month’s world premiere of The Shining, an opera adapted from Stephen King’s 1977 horror novel, the art form just got a little broader. And maybe for non-opera fans, a little more relevant too.

To most people, opera is spear-wielding women in helmets, or maybe hefty people over-emoting in Italian. Not a plaid-clad recovering alcoholic writer’s descent into homicidal madness at a snowbound hotel in the Rockies. But with this month’s world premiere of The Shining, an opera adapted from Stephen King’s 1977 horror novel, the art form just got a little broader. And maybe for non-opera fans, a little more relevant too.

“There will be opera lovers [in the audience], but what I really hope is there will be people who have not gone to the opera before,” Mark Campbell, who wrote the libretto for The Shining, told Minnesota Public Radio. The opera opened on May 7 at the Minnesota Opera.

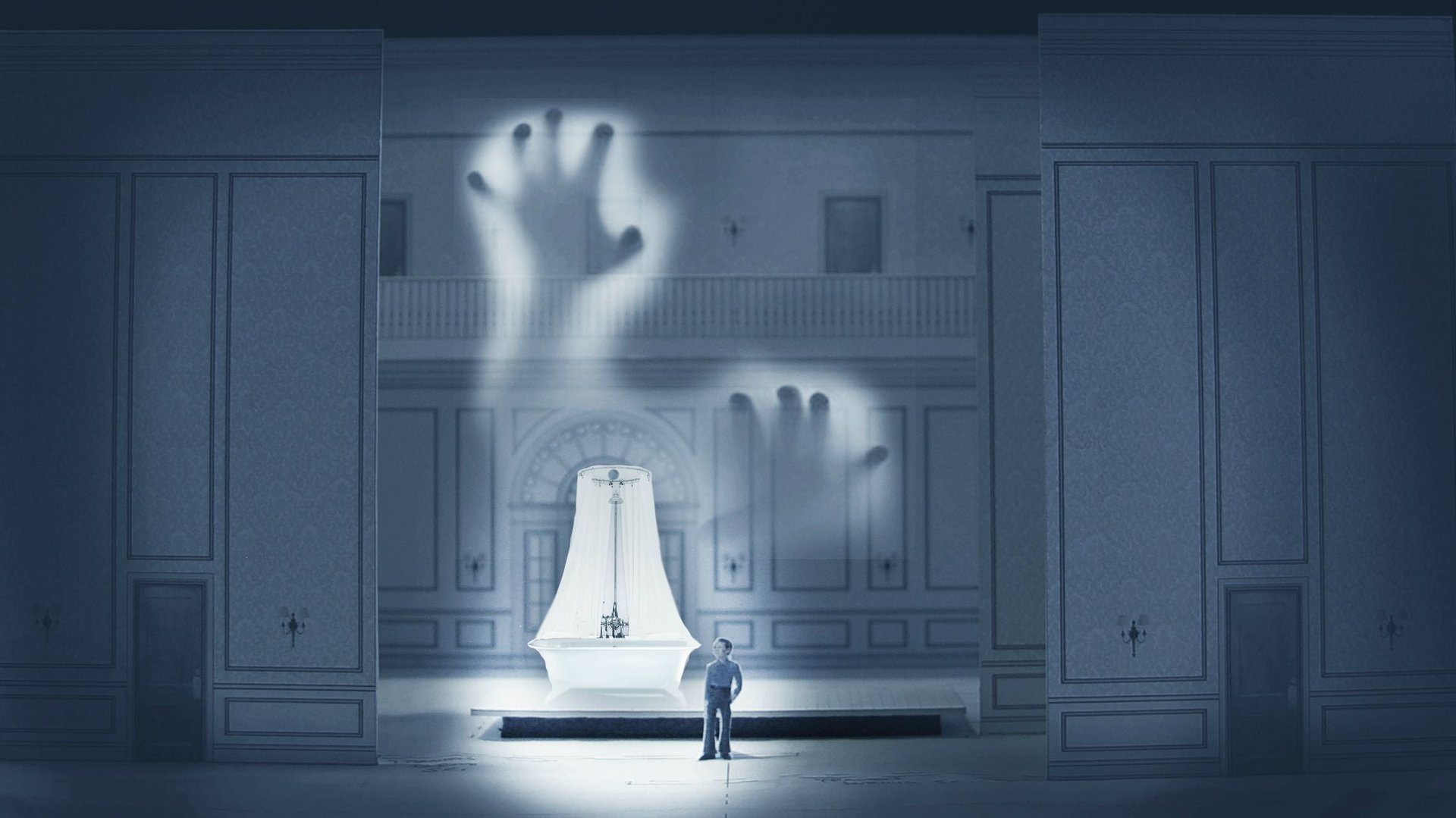

Composed by Paul Moravec, the opera follows the story of Jack Torrance, an aspiring playwright with an increasingly violent temper, after he takes a job as the winter caretaker of The Overlook Hotel, a Colorado resort closed for the offseason, bringing along his wife and son. The Overlook’s resident coterie of sinister ghosts appeal to Torrance’s darker self, urging him to murder his son, Danny.

The Shining, which has received solid reviews so far, sold out many weeks in advance. Few operas these days are so fortunate. The art form is struggling to attract younger audiences and convert curious attendees into full-blown fans. New York’s Metropolitan Opera, the world’s biggest and most important opera company, has confronted this challenge by rolling out spiffy—and expensive—new productions of mostly 18th- and 19th-century operas. Box-office sales suggest this strategy has foundered again this year.

The Minnesota Opera, however, has taken a wholly different approach. The Shining is part of its New Works Initiative, a plan to engage new audiences by commissioning and premiering new operas. The Shining is the company’s 44th world premiere.

Opera-goers shouldn’t expect a musical version of Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film adaptation, which starred Jack Nicholson. The movie’s plot and tone differ markedly from the book’s. In fact, King detested Kubrick’s interpretation, condemning in particular the director’s vision for Wendy, which he called “one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film.” Moravec and Campbell said they aimed to be true to King’s novel, not the movie. (Evidently they succeeded; King approved the libretto within a day of receiving the final version, reports Operavore.)

Much of The Shining—the novel, that is—is made up of the characters’ private reflections and feelings. This makes it unusually ripe for operatic treatment, Moravec said. The music conveys the tension building in the characters’ internal worlds as Jack’s sanity unravels (you can listen to clips here).

As an opera drawn from modern source material, The Shining is hardly unique. Other recent works non-opera fans might be familiar with include Doubt, The Manchurian Candidate, Cold Mountain, The Handmaid’s Tale, JFK and Everest (an opera version of Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air). Some new operas draw directly from real-life events; Nico Muhly’s Two Boys was based on a Vanity Fair article about a sordid internet crime. Others are biographical—X (about Malcolm X) and The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, for instance.

The Shining isn’t the first Stephen King novel to be staged and set to music. A Broadway musical of Carrie was a legendary flop when brought to the stage 1988 (and it received middling reviews when it was revived off-Broadway in 2012). And an opera of Dolores Claiborne premiered in San Francisco in 2013 to generally good reviews. Given King’s extensive back-catalog of novels and propensity for high drama, The Shining probably won’t be the last.