A match-making service pairs neuroscientists with designers to explain scientific breakthroughs

Scientists are smart. Designers are, er, good with color.

Scientists are smart. Designers are, er, good with color.

Stereotype holds that scientists and designers are vastly different thinkers: Scientists are exacting and objective, while designers and artists are intuitive and associative. Science is regularly equated with substance, and design with surface aesthetics—to the dismay of many designers.

The fact is that brilliant designers and artists have helped transform science into an intelligible discipline for centuries. From certified medical illustrators who illuminate technical research with visual renderings, to exhibit designers who conjure memorable installations in science museums, to painters who read and translate NASA data into fantastic visions of outer space, there’s a natural and useful connection between these two creative forces of left and right brain thinking.

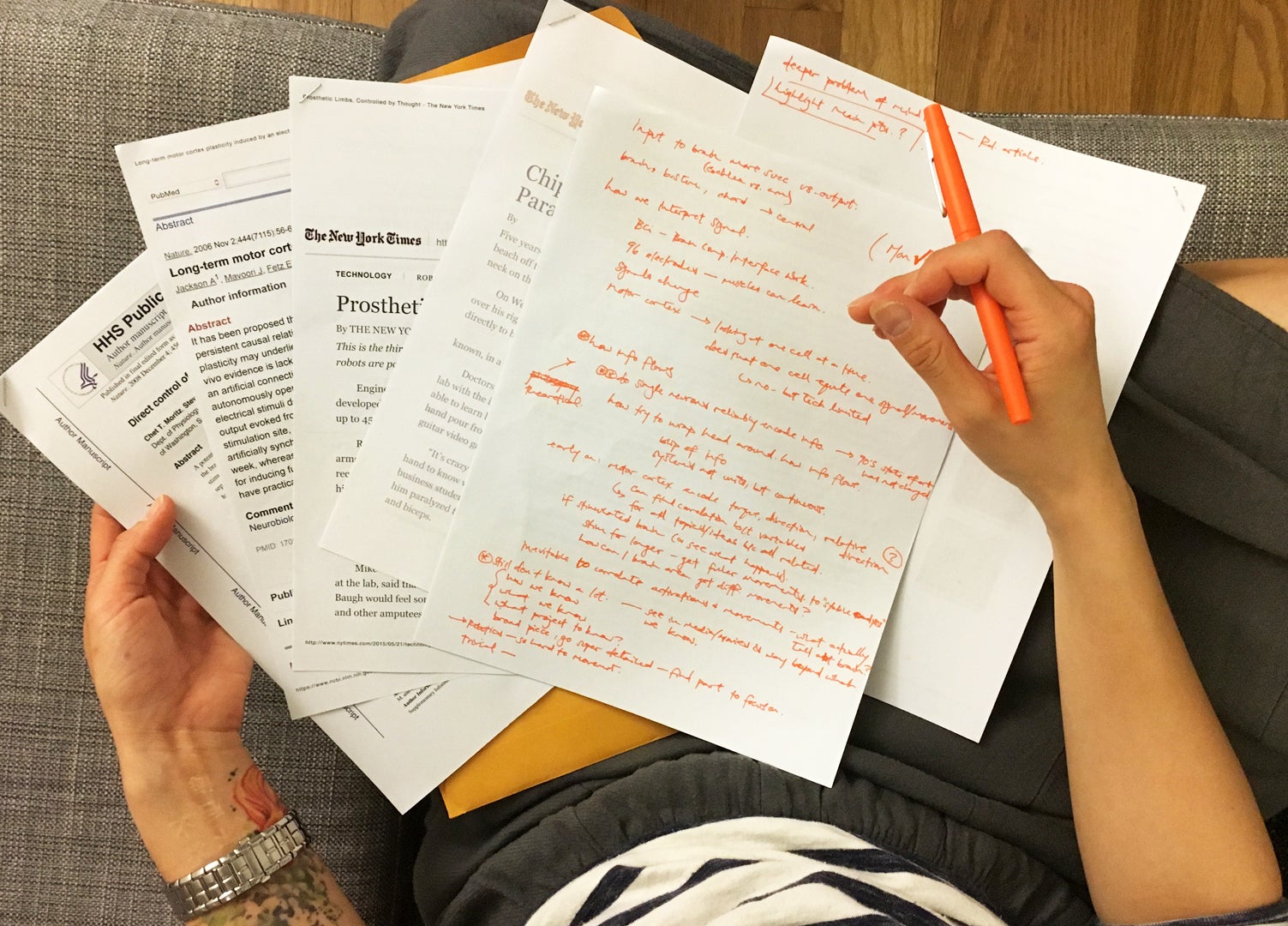

A recent initiative to bridge art and science is a project called Leading Strand. Conceived by neuroscientist-turned art director Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, the start-up pairs academic researchers with design professionals, to create visual representations of scientific breakthroughs, often too technical and abstract for the general public to grasp.

The project’s goal is to counter what Phingbodhipakkiya identifies as “budget cuts, media misrepresentation, and public apathy” toward science in the US. Although scientific institutes such as the National Institutes of Health, NASA and the Department of Energy received a boost in the 2016 federal budget, public funding for scientific research and development has been declining or stagnant since 1968.

Bolstered by a coveted spot in TED’s new residency program, Phingbodhipakkiya works as facilitator and matchmaker for five scientist-designer teams. The teams will reveal their projects at a public art exhibit at Pratt Institute in New York on July 13. Among the projects are a multi-screen motion piece to explain how memory failure happens in aging adults; a chat bot that tracks your mood to demonstrate how physical exercise improves cognition; a drum-circle to show how neurons move when we think; and an interactive film that explores the biological underpinnings of sexual identity and gender.

“It’s proof that design and science make a natural and very complementary pairing,” says Phingbodhipakkiya, who makes every participant sign a contract that commits them to a 50-50 collaboration. “It’s not a client-designer relationship but a real partnership.”

Raising the scientific IQ of the design profession

Having brokered an equal partnership, a project like the Leading Strand could also potentially flip the familiar old equation, in which science provides the substance and designers give form. Could these genius pairings raise the scientific IQ of the design profession too, informing the way we design everything from chairs to cities?

Before formal borders of learning were established, many scientists worked in what would today be considered the domain of designers. In the third century, the Greek multi-disciplinary thinker Eratosthenes charted his observations on paper and created the first map of the world and founded Geography. A more familiar example, of course, is polymath Leonardo da Vinci who painted great masterpieces of the Renaissance, in addition to inventing engineering marvels.

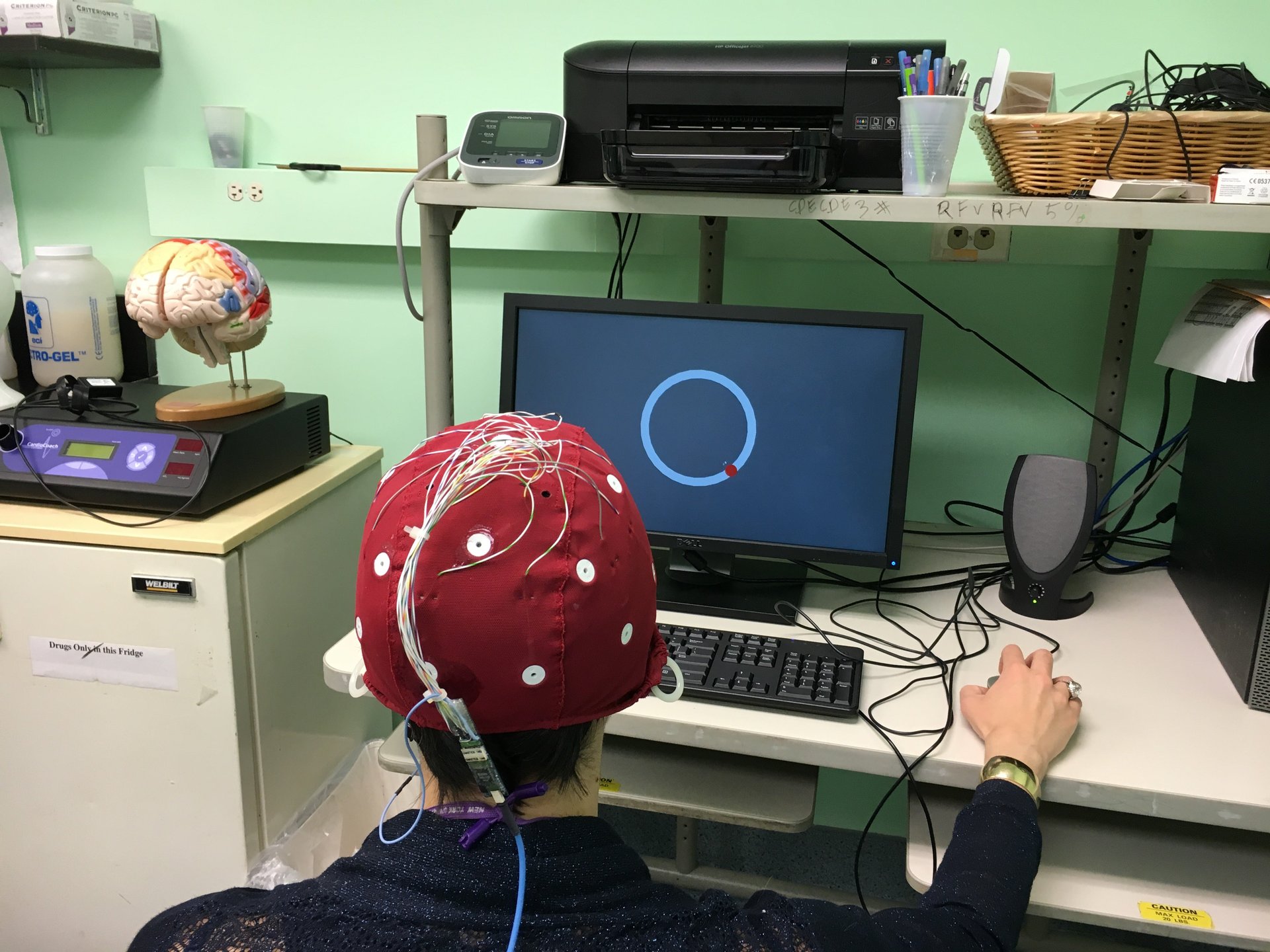

Today, many forward-looking companies draw from neuroscience to shape their products design and marketing tactics. Apple and Tiffany’s use insights from haptic communication—the study of how tactile stimuli shape the brain and its consequences on how a brand is perceived—to create covetable product packaging. Specialized architecture firms employ doctors on their staff to advise on the most effective floor plans for hospitals, and professional organizations like the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture use the latest breakthroughs in brain science to inform the shape of buildings.

At a graphic design conference in San Diego in April, perception psychologist Dr. Thomas Albright urged his audience to consider scientific insight more seriously. ”You might be wondering what does neuroscience have to do with design…but an appreciation of how the brain works ought to help us understand how to create good design.”

A simple way to bolster design with science would be to inculcate a better understanding of research methodology in young designers. It’s common to hear designers scorn focus groups that meddle with their artistic intuition or quash innovative ideas. But as influential sociologist Robert K. Merton, the father of focus groups, has argued, research and polls should be sources of ideas, instead of tools for validating concepts.

Phingbodhipakkiya says that the Leading Strand could educate designers on how best to test their concepts. “Understanding what ‘statistically significant’ means is something design students can learn from scientists,” she says of the kind of casual office polls that designers typically do to test their initial ideas. “An n of 1 is not good research. Asking two of your friends who sit next to you is not good research.”

Whatever art projects emerge from their collaborations, at the very least these 10-week partnerships may prompt the first step of collaboration between design and science, by helping correct misconceptions between participants. “I was in a way surprised that scientists are pretty creative, despite the perception most people have about them,” reflects graphic designer Alisa Alferova, who is partnered with neuropsychologist Dr. Yaakov Stern.

Increasing the amount of good science within good design is critical at a time when brands tempt consumers with catchphrases like ”scientifically-proven” or “designer-made.” Just as Renaissance scientist-artists drew on both sides of the brain to come up with incredible new ideas, so might collaborations between these two fields help produce breakthroughs worthy of the hype around them, today.