How state politicians are quietly working to steal the US presidential election

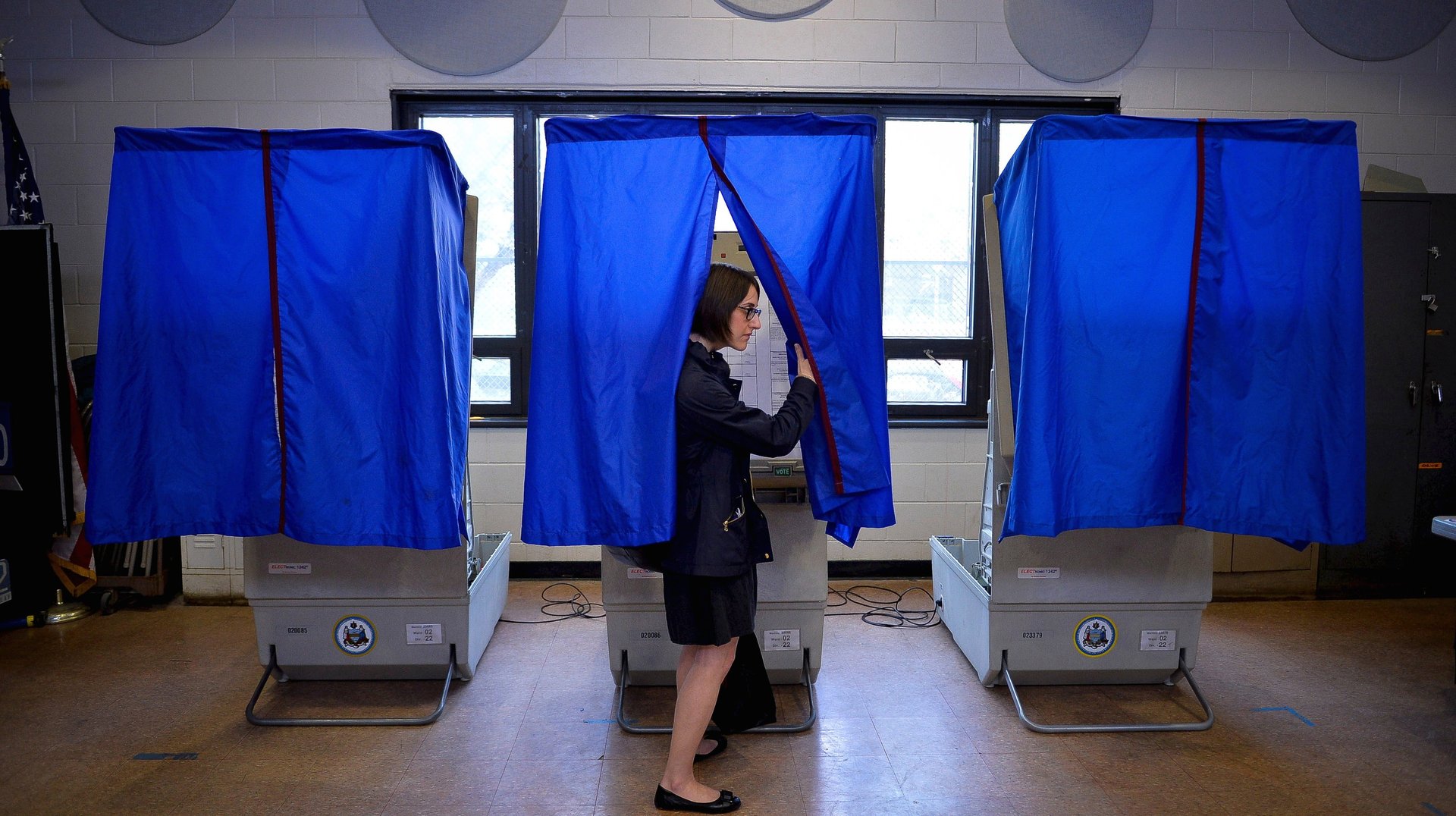

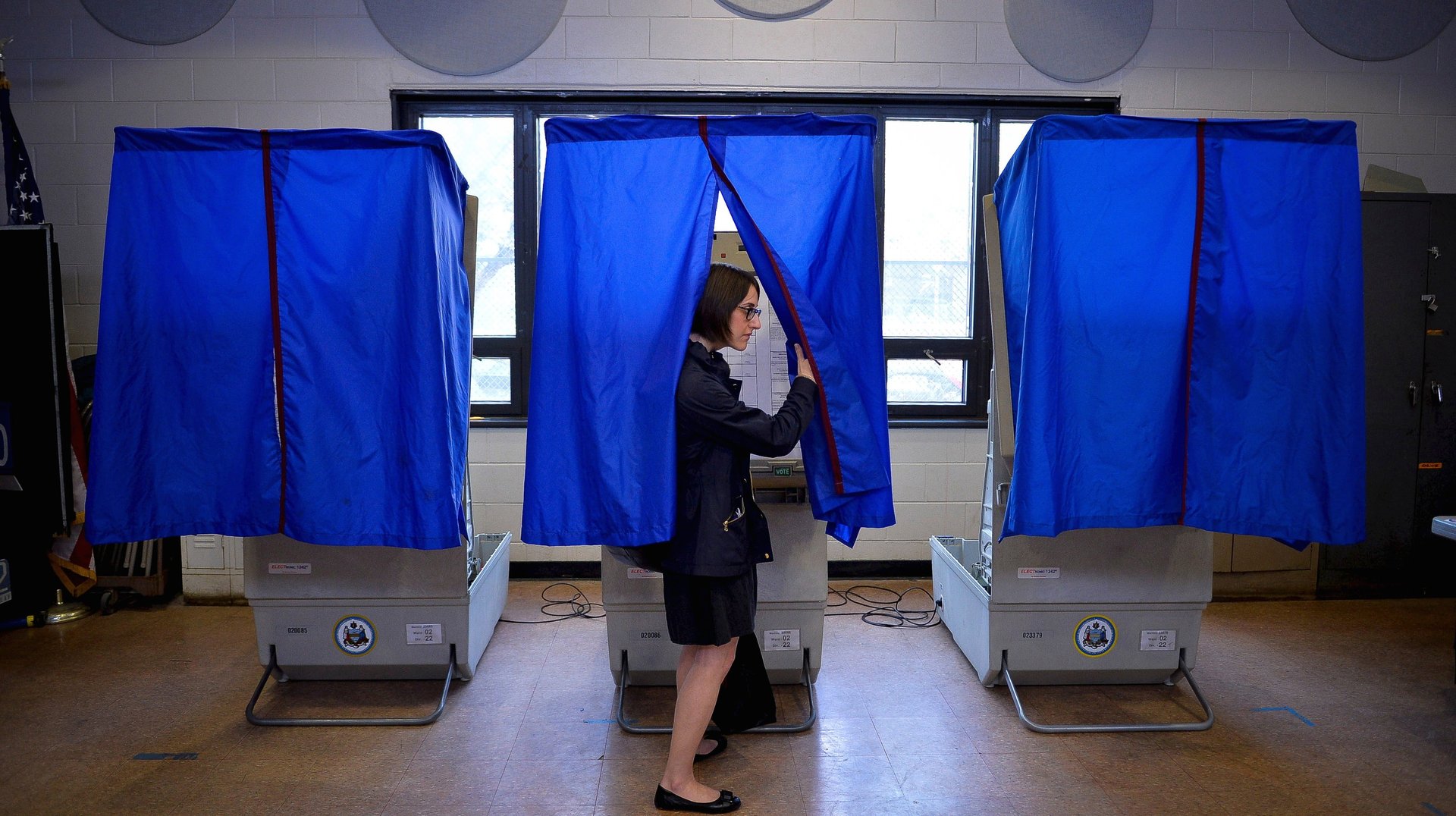

In early May 2016, the Missouri state legislature submitted a bill to the governor requiring that citizens must show photo ID in order to vote. Democrats staged an all-night filibuster opposing the measure, noting that it could potentially disenfranchise over 220,000 voters who who lack proper ID. Missouri attorney Steve Harman noted the bill would most likely affect black Missourians—11% of the population—and that it echoed the political aims of Jim Crow. As is true in most states, there has never been a case of voter fraud in Missouri history, leading many legislators to question the true intent of the law.

In early May 2016, the Missouri state legislature submitted a bill to the governor requiring that citizens must show photo ID in order to vote. Democrats staged an all-night filibuster opposing the measure, noting that it could potentially disenfranchise over 220,000 voters who who lack proper ID. Missouri attorney Steve Harman noted the bill would most likely affect black Missourians—11% of the population—and that it echoed the political aims of Jim Crow. As is true in most states, there has never been a case of voter fraud in Missouri history, leading many legislators to question the true intent of the law.

Missouri is known as “the bellwether state,” having voted for the winning candidate in all but one presidential election between 1904 and 2008. Obama lost the state in both elections, but in 2008, he lost by a mere 3903 votes. Imagine what that result would have looked like had 220,000 voters—among them his black Democratic base—been unable to cast their ballots.

In swing states like Missouri, voter ID laws that disenfranchise non-white voters could potentially influence the outcome of national elections. In this case, purple states like Missouri may in the future turn blazing red.

Missouri’s law will not be passed in time to impact the 2016 race. But it is part of a growing trend of states that have passed or moved toward restrictive voter ID laws as America’s population grows increasingly diverse. In 2016, 17 states will have new voting restrictions in place for the first time in a presidential election: Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Of these states, Arizona, Georgia, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, and Wisconsin have been identified as swing states. Others are newly ambiguous: Texas, a state that has voted Republican since 1980, is now less of a sure bet. After GOP frontrunner Donald Trump proclaimed Mexicans “rapists” in the summer of 2015, applications for citizenship and voter registration among Texan Latino immigrants soared, and polls have shown a tight race. But will the new voters be able to cast their ballots? Under current regulations, an estimated 771,300 Texan Latinos, many of them recent immigrants, lack the required ID.

Since Trump became the de facto Republican nominee, some pundits have claimed his loss is all but inevitable due to demography, as whites comprise only 69% of eligible voters. Throughout the primaries, Democrat Hillary Clinton has retained the support of the Obama coalition, a diverse array of black, Latino, and both white and non-white female voters, with black women her most reliable supporters. These three demographics currently also hold the most negative opinion of Trump, with 91% of black voters, 81% of Latinos, and 75% of women rating him as unfavorable according to a Washington Post/ABC News poll conducted in early April 2016.

However, there are several reasons why demography may not equal destiny for Democrats. A high unfavorability rating does not predict voter outcome. In most elections since 1980, the candidate with the highest unfavorability rating has usually won. Unfavorability is a particularly poor predictor in a contest between two widely loathed candidates: Clinton’s unfavorability rating, currently at roughly 40%, is the second highest in US history—second only to Trump’s at roughly 50%. Marginalized voters are also not monoliths; individual voters prioritize individual issues, and it is possible that deeply held beliefs on an issue like abortion could sway a voter to the Republican side.

For white voters, opposing the ascendency of Trump may be an abstract moral imperative, but for non-white voters, a president Trump could have direct and dire ramifications. Soaring Latino registration speaks not only to disgust with Trump’s anti-Mexican rhetoric, but a worry that he will act on his promise of mass deportation, tearing families apart.

Black citizens, the demographic group with the longest history of US disenfranchisement, now contend with a candidate who has favorably retweeted white supremacists, appointed a white supremacist as a delegate, waged an obsessive “birther” campaign against the first black president, and was sued twice for discrimination against blacks. While Trump has not targeted black citizens in his rhetoric as directly as he has Muslims and Mexicans, it is reasonable to assume black Americans would not benefit from a Trump presidency.

Black and Latino voters have the strongest practical motive to rally against Trump, but they are also the two groups most likely to be blocked at the polls. In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated part of the Voting Rights Act, stating that “our country has changed”—apparently not realizing these changes included a GOP frontrunner endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan. The ruling cleared the way for new restrictions impossible to implement before the 2012 election.

The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) Education Fund estimates that the new voter ID laws will impede over 875,000 Latinos from voting—many in confirmed swing states like Arizona or newly ambiguous states like Texas. The laws may also determine the election in swing states with large black populations. North Carolina’s new photo ID requirement will mostly likely impact poor and black citizens who traditionally vote Democrat, a critical bloc in a state where Obama won in 2008 by only .32% of the vote. Wisconsin’s photo ID could potentially block 300,000 voters, most of them non-white: so far over 60% of requests for a photo ID to vote have been from black or Hispanic voters. Virginia’s voter ID law has already disenfranchised poor black voters who cannot afford or obtain new photo IDs. It’s an outcome which should surprise no one; in 2014, the law was predicted to disenfranchise 200,000 voters.

The ascendency of Trump to frontrunner status—an outcome most pundits initially predicted was unlikely—shows that nothing in this election should be taken for granted. Assuming race will determine the winner in November is not only reductive and lazy, but ignores the fact that many black and Latino Americans may not be able to vote at all. That swing states with high non-white populations are among those implementing the new restrictions should give every prognosticator pause.

There is no certain electoral outcome. But there is still time to help potentially disenfranchised voters procure the necessary ID and understand the new restrictions so that they are able to act on their constitutional right to vote. Demography will not determine the election. But complacency might.